KUALA LUMPUR, June 3 – We live in an age of irony when it comes to cancer care. On the one hand, cancer treatment and research are evolving at breakneck speed, with targeted therapies promising to be less invasive, more precise, and more effective.

On the other hand, the cost of treatment is also increasing, largely attributed to soaring drug prices — denying access to treatment to the very people who need them. The estimated cost to treat cancer in Malaysia can go up to as high as RM395,000, though prices may vary based on the type of cancer, with different private hospitals charging different rates.

This very often does not include long-term post-hospitalisation treatment charges and non-medical costs incurred during care-seeking, including transportation, food, caregiver costs, and loss of income.

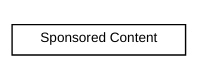

Society for Cancer Advocacy and Awareness Kuching (SCAN) founding president Sew Boon Lui, who is living with metastatic or advanced breast cancer, recently shared that her CDK4/6 inhibitor targeted therapy drug costs over RM6,000 per month for each cycle, while her chemotherapy drug costs more than RM5,500 every three weeks.

Sew also goes for positron emission tomography (PET) scans, used to detect new or recurrent cancers, every two to three months since last September. The price for the PET scans saw an increase recently from RM2,800 to RM3,000 for each scan, Sew said.

While Sew’s initial diagnosis and treatment was covered by a lump sum payout of a critical illness insurance claim, her later metastatic breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, as well as latest intravenous (IV) chemotherapy treatment were largely paid out of pocket.

Sew also receives financial assistance under a patient assistance programme and the Social Security Organisation’s (Socso) invalidity pension scheme, though Sew said the amount is sufficient only for “basic living expenditure”.

“You may say, ‘Oh, you’re a recipient of the Socso scheme’. Yes, I am, but the monthly pension scheme I receive, compared to the drug that I have to pay now, RM5,500 plus for every three weeks, the Socso scheme can only support one quarter of my drug.

“Not to talk about the PET scan, that is additional expenditure,” Sew said during a panel discussion at the “Oncology Summit 2022: Meeting the promise of cancer care in Malaysia” hybrid event organised by the Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy and pharmaceutical company Takeda Malaysia last April 30.

“So, it is a burden, but I know that my supportive husband will continue to support me and God has been blessing him with projects, so [there’s] enough earnings so far to sustain through all this while.

“But overall, I must say there’s actually limited sources of assistance,” Sew said. “We always say, ‘yeah, we have assistance and financial aid from certain NGOs’, which are good, but when it comes to metastatic breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, this little subsidy is probably not significant enough, not really helping enough.

“I really wish there will be a cancer foundation in the near future to help patients, like those with metastatic breast cancer or metastatic cancer of other types, to be able to get better and stronger support financially,” Sew added.

Lower Cancer Survival For Poor Patients

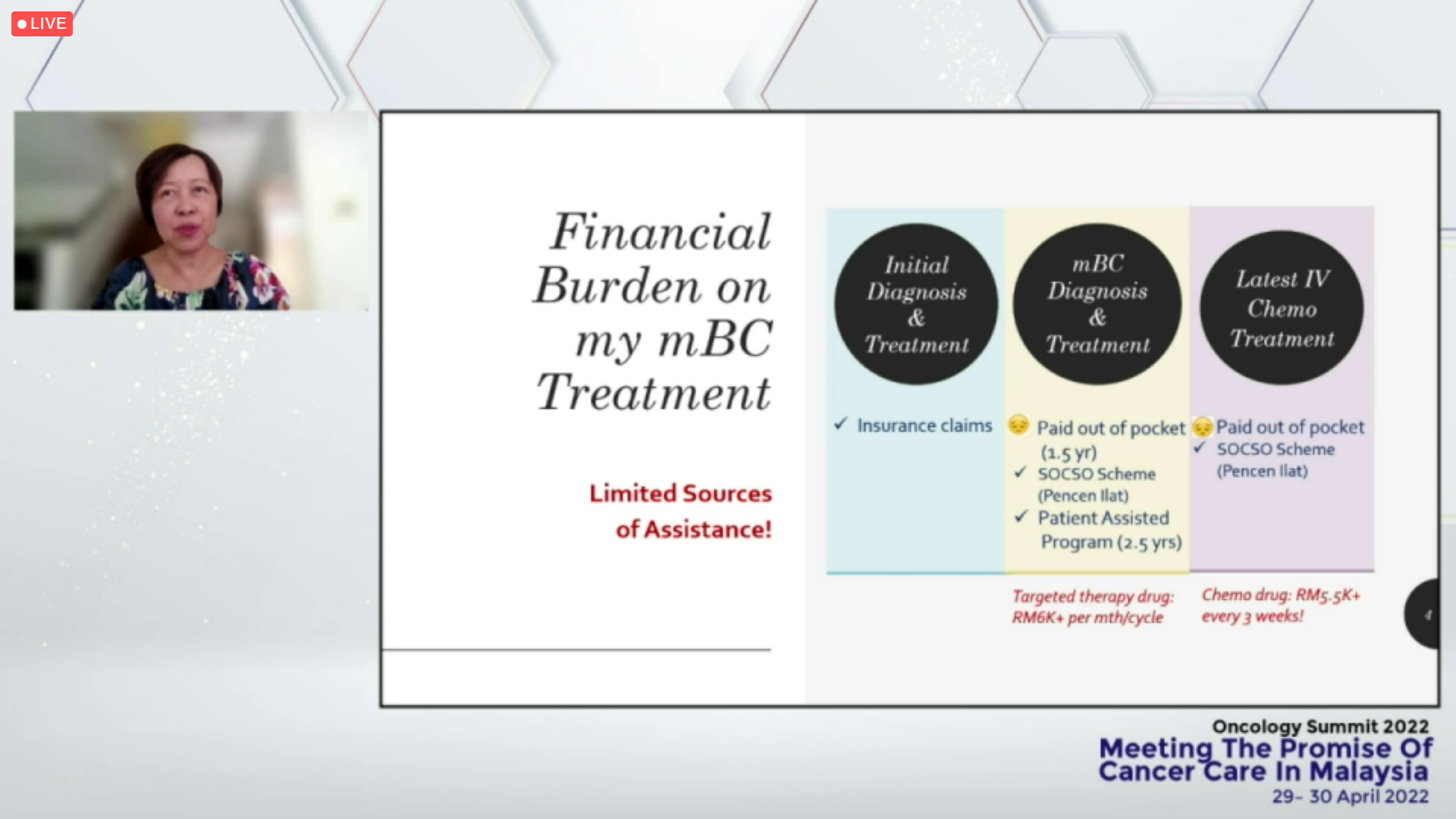

The disparities in cancer survival between high-income and low-income breast cancer patients in Malaysia. Picture from Cancer Research Malaysia (CRM) patient navigation programme manager Maheswari Jaganathan’s presentation at the “Oncology Summit 2022: Meeting the promise of cancer care in Malaysia” on April 30, 2022.

Despite her unique challenges, Sew is among the luckier ones who have been able to afford treatment.

Access to treatment – not just awareness – continues to be a challenge for many cancer patients, especially those from the bottom 40 per cent (B40) income group.

According to data compiled by Cancer Research Malaysia (CRM), high-income breast cancer patients in Malaysia have a higher survival rate of over 90 per cent compared to low-income patients with a less than 65 per cent chance of surviving the disease.

Maheswari Jaganathan, patient navigation programme manager at CRM, said while the overall five-year breast cancer survivorship in Malaysia has improved to 67 per cent in recent years, this predominantly involves high-income women.

“If you compare it to the low income women, they are not ‘breast aware’. There’s still less than 10 per cent of them who attend breast cancer screening, mostly presented late and sometimes, a second opinion comes from alternative medicine.

“Most of them have access to public health care, but limited access to target therapies, therefore, their survivorship is less than 65 per cent,” Maheswari said.

Treatment costs do not only cover medicine, but often hidden ones like travel expenses that can “double or triple” for patients from rural areas, Maheswari said. Longer trips to city centres like Kuching or Kuala Lumpur also meant extra days or a week’s worth of unpaid leaves for those with no direct access to treatment.

Sew, who is based in Sarawak, said beyond health literacy, lack of financial support often becomes a factor that prevents patients from seeking earlier treatment for their cancer.

“The key issue is that Sarawak is just too huge and people in the northern area often find it very tedious to make a trip to Sarawak (Kuching), like from Miri and so on. It can mean travelling 800 kilometres away, and more so for people staying in the rural area.

“You can say that because of health literacy they don’t want to come out, but a lot of times, more so it’s because they cannot be putting down their jobs for three days or five days, just come all the way to treat a lump – a lump to them is just a lump, there may be no pain in the beginning – so they may take it as, ‘Yeah, maybe later, maybe next time’.

“So, that is probably a hindrance,” Sew said. “How are they going to make the trip and how much money will they lose, you know, when they have to take three days to a week to make a round trip.”

More People Turning To Private Health Insurance

In Malaysia, the increasing cost of health care services and treatment means that people have been forced to spend more from out of their own pockets.

CodeBlue previously reported a tripling of out-of-pocket (OOP) health care spending in the country to RM23.15 billion in 2020 from RM7.14 billion in 2006, with 43 per cent of OOP spending in 2020 going to outpatient services, Ministry of Health (MOH) data showed.

To compare, private insurance (other than social insurance) spending on health amounted to RM4.95 billion in 2020 – about 78 per cent less than OOP spending that year.

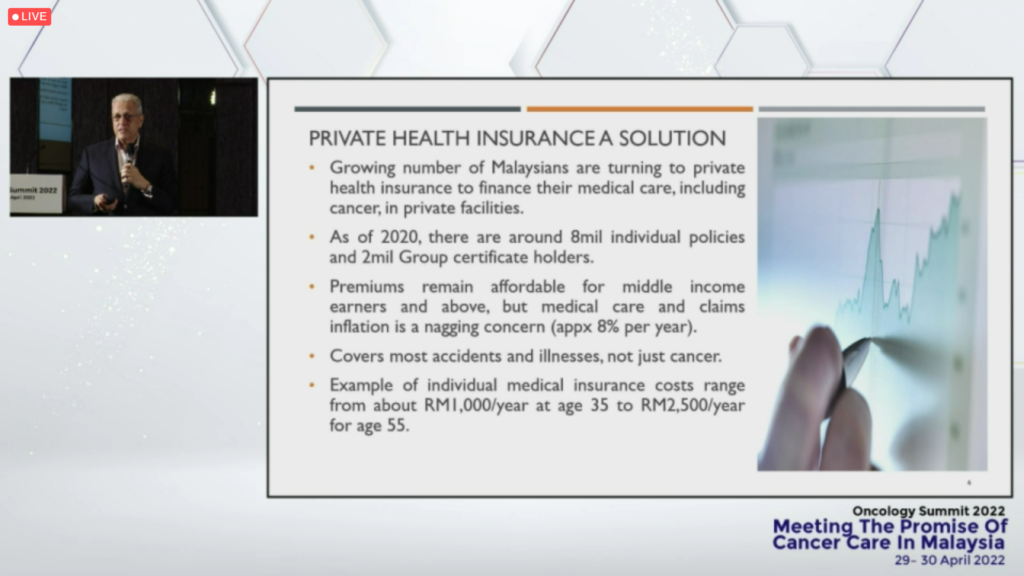

Despite the wide gap between private insurance and OOP health spending, Life Insurance Association of Malaysia (LIAM) chief executive Mark O’Dell said there has been an increase in the number of Malaysians who are turning to private health insurance to finance their medical care, including for cancer, in private facilities.

O’Dell said there were around eight million individual policyholders and two million group certificate holders, as of 2020, with the number growing by about 500,000 people a year.

“So, more and more people are turning to private medical insurance. Premiums remain affordable for middle-income earners and above. But medical care and claims inflation is a nagging concern.

“A study done by the industry from 2013 and 2018 showed medical claims inflation to be around 8 per cent. There have been other numbers reported that the number is even higher, and this is not unique to Malaysia. Medical care inflation and medical premium inflation is a global issue and the 8 per cent, actually, you may be interested to know, is on par with global figures,” O’Dell said.

Individual medical insurance costs range from about RM1,000 per year at age 35 to RM2,500 per year for age 55, O’Dell said.

Another important coverage, on top of individual medical insurance, is critical illness, O’Dell added, as was highlighted by Sew in her presentation.

“This is separate from individual medical insurance and is often attached to a life insurance policy, and it pays a lump sum upon diagnosis, as opposed to paying for a hospital or inpatient hospital care.

“And this can be very important because it provides needed monies and financing for post hospitalisation treatment costs. It can help with non-medical costs such as travel, lodging for family members. It can also help in replacing lost income while recovering. And so, this is a very popular coverage, but it often goes overlooked.

“Sometimes people think that they have medical insurance, individual medical insurance, they don’t need critical illness (insurance), and we’ve seen already the gaps that private medical insurance may present and so, critical illness is very important,” O’Dell said.

According to the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019, only 22 per cent of the Malaysian population are insured with personal health insurance (PHI), with 36 per cent of the uninsured population claiming that PHI is not necessary, and 43 per cent unable to afford PHI.

Cancer Care Spending As An ‘Investment’

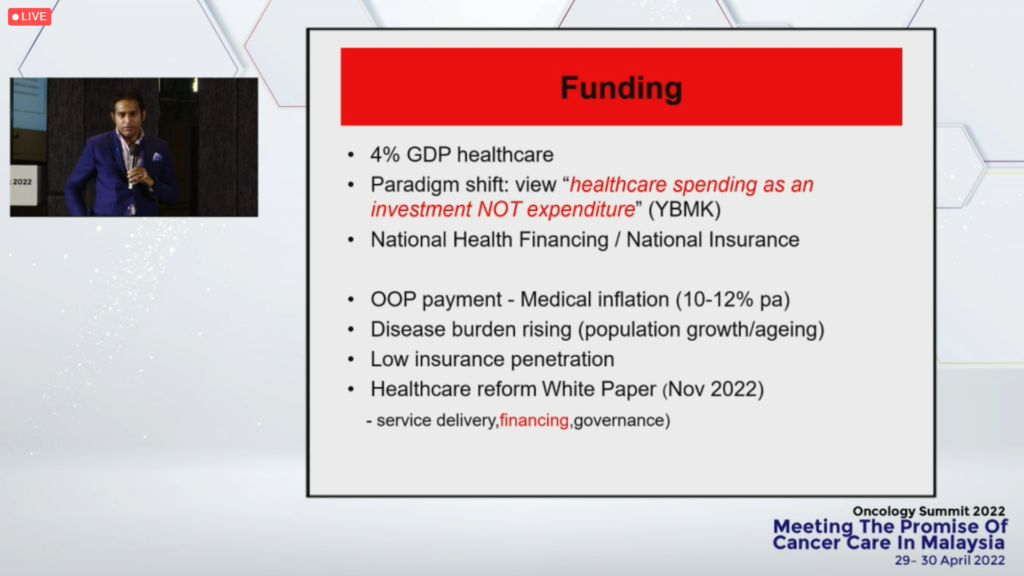

Dr Anand Sachithanandan, a cardiothoracic surgeon and co-founder of Lung Cancer Network Malaysia (LCNM), urged for a shift in thinking, echoing Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin’s call for health budgets to be viewed as “investments” rather than expenses.

Dr Anand said “frank discussions” are needed on how the country plans to fund future health care, particularly cancer care, whether it is a form of national health financing or insurance, with rising OOP payment and medical inflation estimated at 10 to 12 per cent per annum.

“What does that mean? In a given period of a decade, we will see a doubling of the cost of a particular treatment or surgery,” Dr Anand said, noting that targeted therapies for lung cancer can cost between RM10,000 and RM20,000 per month, with some patients requiring treatment for two to three years.

“In terms of treatments, we really are truly in this era of precision diagnostics, personalised medicine, and bespoke therapies. We’ve heard from our previous speaker (Sew), in terms of the different tests and targeted therapies.

“Allow me to say that, for example, in the area of lung cancer – and we can extrapolate and use this for many cancers – we now are in the era of genomic molecular profiling, something called next generation sequencing (NGS) which is a scalable technology that allows for sequencing, quite rapidly, large chunks of genetic material and allows us to identify mutations that are present in the cancer in the tumour, and that in turn, makes it amenable to treatments with targeted therapies which are far more effective and less toxic.

“Unfortunately, these diagnostic tests, NGS, and the drugs that are used to target these sorts of lesions or mutations are very expensive,” Dr Anand said.

In other words, cancer care is complex.

“The disease is complex; no two tumours are the same, no two patients are the same. Optimal care usually requires a multi-disciplinary approach, a multi-modal approach.

“It’s a given that if we can pick up the disease earlier, there are better outcomes. It’s more amenable to treatments with a curative intent, it is more cost-effective and less financially toxic to the cancer patient, to their caregivers, and to society at large,” Dr Anand said.