KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 27 – Since October 1, Sabah has been reporting three-digit Covid-19 cases every day and yesterday, the state reported its highest daily tally of 927 infections.

In CodeBlue’s interviews last week with frontliners on the ground in Sabah, they highlighted that hospitals lacked manpower, patients had to wait for up to two days to get into the intensive care unit, doctors were getting burnt out, and Covid-19 cases were everywhere in the community. However, the Ministry of Health (MOH) has disputed claims that Sabah’s health care system is under collapse, claiming that hospital beds are still sufficient for Covid-19 patients.

CodeBlue interviewed former Health deputy director-general (public health) Dr Lokman Hakim Sulaiman to get his suggestions and opinions on the outbreak in Sabah, as he urged focus on the Sabah and Labuan coronavirus outbreaks. Below is CodeBlue’s Q&A with the professor in public health:

Covid-19 cases in Sabah are everywhere. To quote a doctor in Queen Elizabeth Hospital, “it is everywhere like Ground Zero”. Does this mean that most Sabahans will end up contracting Covid-19 and we just have to hope that they can pull through on their own?

As long as the infection continues unchecked, it will continue to spread. But we have to remember that based on current strategy (targeted screening), the number of cases detected is depended on the number of testing, the more you test, the more you detect, including those who got the infection but do not suffer from the infection (asymptomatic carrier).

MOH has confirmed before that overall, large majority of the positive cases were asymptomatic or mild cases. For example, school children, adolescents and young adults, although they are susceptible to the infection, large majority are asymptomatic or only have mild infection. However, those elderly and those with underlying medical conditions are at higher risk of severe infection and therefore, they should be the one that need to be protected.

Unless MOH can show that in Sabah the pattern (age specific case fatality rate) is different and unique, I believe the pattern is similar to this global pattern. Some have pointed out that number of death (case fatality) is higher in Sabah.

First, show the comparative differences in case fatality between Sabah and the rest of Malaysia. Even if it is true, my take is that it is not so much of the differences in the infectivity, transmissibility and pathogenesis of the virus strain circulating in Sabah but rather mainly contributed by the socio-economic-demographic and logistic issues.

The state is big, bigger than peninsular but sparsely populated. Major health resource centres such as the district health office, health centres, and hospitals are located in major towns which are very far apart. It takes hours for example to transfer a sick patient from Kunak to Lahad Datu or Tawau.

Hospital resources and capacity is also much limited compared to Peninsular. I believe the socio-economic and socio-demographic factors play significant role in determining the rate of spread, effectiveness of containment measures, and the overall outcomes of the infection.

Currently, we are pouring our resources into Sabah, while slowly, cases are also rising in Selangor. At what point should we stop?

To avoid humanitarian crises, MOH has no choice but to strengthen the health system in Sabah by mobilising resources from other less affected states.

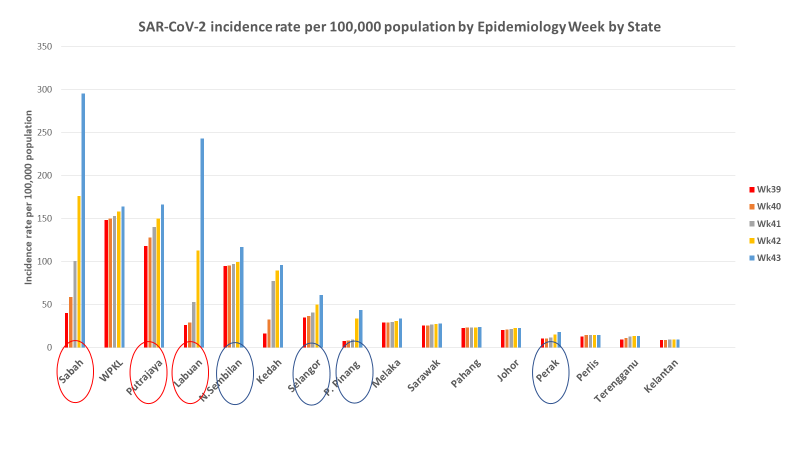

However, I must caution that, not only Sabah, MOH must pay attention and provide urgent support for Labuan, which is also facing exponential increase in weekly incidence rates over the last one month (see Figure).

In epidemiology, the absolute number of cases is just a number which carries little significance, but the incidence rate reflects the population at risk. The higher the incidence rate, the higher the risk of infection in a given population.

Thus, you can see that even though the absolute number of cases in Labuan is very small relative to Sabah and Selangor, the risk of Labuan people to be infected is much higher than Selangor and almost matching that of Sabah.

If drastic action is not taken by MOH to also help Labuan, I am afraid the health system in Labuan can also be overwhelmed with potentially catastrophic outcomes. Remember, Labuan is an isolated island with a small district hospital and health capacity.

In this context, I would say that the situation in Selangor is still very much under control. And remember, in Selangor, it has among the most advanced health system infrastructures, both public and private.

Klang Valley has the highest concentration of health care facilities in the country. For example, even though private hospitals are not involved in managing Covid cases at the present moment in the Klang Valley, if the situation gets worse, I am sure it is already in MOH’s preparedness plan that these private resources will also be utilised. In fact, some degree of outsourcing of private services is already happening.

To me, I am least worried about Selangor and Klang Valley, including Kuala Lumpur. However, I must caution MOH to closely watch out for Putrajaya, which continues to show a steady increase in Covid-19 incidence and, this week, Negeri Sembilan.

I am not overly concerned with Kedah, although the reported Covid-19 incidence rate is quite high. The outbreak in Kedah is related to the confined prison population and its staff quarters. As long as the Enhanced Movement Control Order (EMCO) is maintained and SOP is strictly followed, the infection should be able to be contained. Similarly, Penang follows the pattern of Kedah with the outbreak occurring in the prison population too.

What we can learn from this is that if we can take effective measures to manage infection in a population in a confined environment like prison and detection centre, we should be able to contain its spread to the outside population. Because of the nature of such an environment, we can expect the number of cases to increase rapidly, but it will also subside quite quickly too.

But if we fail to recognise the risk and fail to manage the situation accordingly, it can easily spread out to the staff and later to the general public, as what happened in Sabah.

From the figure, we can also say that the other states – Melaka, Negeri Sembilan, Johor, Pahang, Terengganu, Kelantan, and Perlis are all under control.

So, we must mobilise the resources from the less problematic states to other states that needed more help. When in crisis, we must also mobilise resources from other agencies as well as from the private sectors and civil societies.

Having said that, MOH must critically appraise their surge capacity. MOH has had the opportunity to do that and address the shortcomings during the first nationwide Movement Control Order (MCO). Indeed, that was the main objective of the national lockdown in the first place, to flatten the epidemiologic curve so as to buy time for the country to prepare itself for the worst to come.

We should have anticipated that the worst can come anytime because we do not have any effective drug to treat and vaccine to protect from the infection at the present moment. We should have been ready to face the current wave because all those preparations should have been carried out during and after the first MCO.

But I am very concerned, despite the Ministry’s claim that its diagnostic capacity has increased significantly to 58,466 tests a day, but we are still having the problem of backlog in pending lab results for Sabah, which run into thousands a day.

Our hospital capacities may have been adequately prepared with thousands of ventilators on standby and further enhanced by our capacity to quickly establish field hospitals/low risk centre. However, I do not see similar enhancement in the surge capacity of the real frontliners, the rapid action team of the public health programme.

No matter how sophisticated your hospital is, if the public health frontline collapses, the hospital will quickly be overwhelmed, and the entire health system will collapse with disastrous consequences.

It is important to give equal priority to preventive and promotive (health education) care component of the health system. Maybe this has been taken care of, but was not publicised. The front line needs more staff to investigate every case and cluster, to do contact tracing, take samples under the most enduring environment in full personal protective equipment (PPE) and to monitor and maintain quarantine centres.

By right their man-hours should be limited to eight hours a day, five days a week only so as to avoid fatigue, mental stress and burn which will be disastrous. The teams may work in shifts, which include the weekend and public holidays. They also need enough vehicles to move around quickly, especially when logistics is a challenge such as in Sabah.

Masidi Manjun, Sabah’s Covid-19 spokesperson, said that home treatment for stable patients is allowed in Sabah. Do you agree with this?

When hospitals are already overwhelmed, what choice do we have? It is the most rational thing to do – to prioritise who should be admitted and who should not. I am sure MOH already has the guidelines in place.

In general, those with severe infections and those with higher risk of severe infection and death should be given the priority to be admitted. This include those who are very sick, elderly and those with other co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic lung disease, cancers, and other immune-compromised conditions.

Editor’s note: MOH has denied that positive Covid-19 patients are being placed at home in Sabah, saying Sabah’s health care system still has capacity.

What are your suggested guidelines for home treatment?

I am not sure what the state Minister meant but I am not sure if anti-viral drugs that are prescribed in hospital can be given at home. I don’t think so. But I have been made to understand that under current guidelines, anti-viral is only given to patient with symptoms and those with severe manifestations.

In this regard, those who are symptomatic but have no severe manifestations and no risk factors should be treated in a low-risk centre (field hospital) and asymptomatic should be allowed to be quarantined at a dedicated quarantine centre (separated from quarantine centre for travellers/close contact with negative result). Quarantine at home should be the last resort if we do not have enough quarantine centres.

However, if that happens, cases must be taught the do’s and don’t and to strictly self-monitor closely for emergence of symptoms and warning signs. The quarantine procedure must be strictly enforced and monitored.

How effectively can home treatment of mild cases work in a state like Sabah, especially in rural areas where understanding of the virus itself is poor?

I don’t think we should underestimate the power of community empowerment. If they are adequately educated and trained, they can do a good job. Community empowerment is not something alien in Sabah, Sarawak and the remote communities in Peninsular Malaysia.

There have been numerous success stories in community empowerment in health agenda. One good example is the significant contribution of the Community Health Volunteer (Sukarelawan Kesihatan Masyarakat, SKM) in the control of malaria in Sabah in 1990s and early 2000s.

The SKM were trained to collect blood smears on glass slide and to send it to the nearest laboratory for malaria diagnosis. They were also trained to apply insecticide and to distribute bed-nets that effectively control malaria transmission.

If their older generations can understand malaria transmission and their role to break the transmission without the help of modern gadgets, I do not see any reason why our current generation cannot understand Covid-19 and help to control them.

Many rural communities, including in Sabah and other states, are also involved in KOSPEN initiative, the Community Empowerment for NCD and the same communities are now exposed to Covid-19 infection. Furthermore, the COMBI initiative for dengue control both in urban and rural communities can also be mobilised to help in Covid-19 work.

How can we help the public in rural areas, like the Bajau community, increase their understanding on the virus itself, especially with the lack of manpower?

As in Q5 above, we need to engage and empower these communities through their community leaders. Normally, these people trust their leader more than anyone else, including government officials. As I have mentioned earlier, MOH has had enough experience with community empowerment initiatives.

Certainly, it needs to be adapted to the different challenges of Covid-19, but it is not something that is impossible.

If we did well with malaria, dengue and cholera through community empowerment and participation, I cannot see the reason why we cannot do the same with Covid-19.

Of course, everyone fears any new disease, not only the rural communities, but also the educated urban community. Winning the hearts and minds of these underprivileged communities is a unique skill of true public health professionals, which we have in abundant.

Of course, we need time to win their hearts and minds. We must acknowledge that their ignorance is a huge hurdle. However, we cannot use it as an excuse, but rather, we must work harder to overcome that hurdle. I am sure our ground staff are working hard to do just that and we, civil societies, must continue to support them.