It is unclear why four out of 10 people with coronavirus in Sabah have more severe disease, more than triple the the 12 per cent of Malaysia’s overall Covid-19 cases back in early April who were in the third to fifth stages of disease.

If indeed 80 per cent of general Covid-19 cases in Malaysia are asymptomatic or mild, then the 43 per cent rate of seriously ill coronavirus patients in Sabah could indicate a lack of testing.

Paediatrician Dr Amar-Singh HSS observed high positivity rates of 17 per cent to about 44 per cent in three Covid-19 clusters in Sandakan, Sipitang, and Tawau, as of October 15, which indicates that not enough people are getting tested in those Sabah districts. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a positivity rate higher than 10 per cent means that countries are not testing sufficiently to track undetected coronavirus cases in the community.

The 11 consecutive days of Covid-19 fatalities in Sabah as of yesterday, totaling 44, indicate the seriousness of the outbreak. Only two coronavirus-related deaths in that period were reported outside the state – both in Selangor.

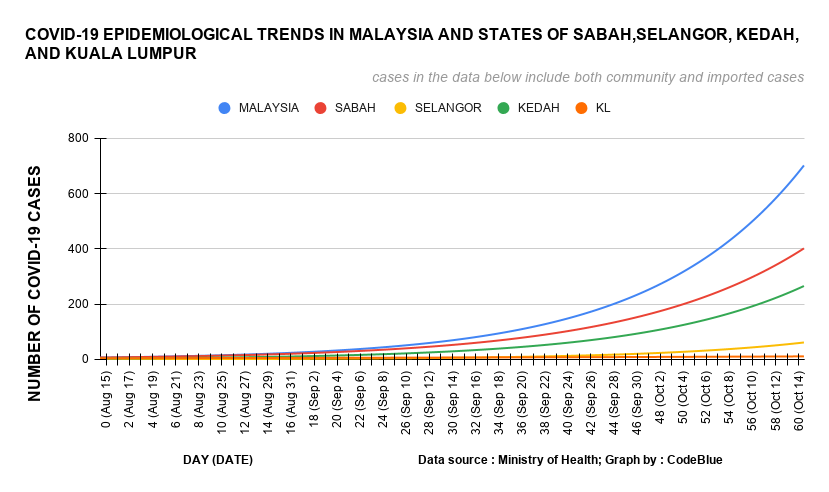

The six official Covid-19 deaths reported in Sabah yesterday were accompanied by a record high 702 coronavirus infections in the state, comprising about 81 per cent of the total 871 new Covid-19 cases nationwide, also another historic high for the country.

The Ministry of Health (MOH) has explained the high figures as backlogged cases, as RT-PCR samples are sent daily to the Institute of Medical Research in Kuala Lumpur. Sabah State Local Government and Housing Minister Masidi Manjun reportedly said 7,000 of 18,000 backlogged test samples have been cleared since the start of the month, or just 39 per cent, amid expanded testing in 15 red districts.

This means that the Covid-19 infections reported recently do not reflect the current outbreak in Sabah, as they are likely a week or so old.

We saw the same problem in the early Covid-19 waves in Malaysia, when public health experts complained about a high number of backlogged cases. The current problem of delayed test results is especially pronounced in Sabah, as thousands of test samples have to be flown over to the peninsula daily, amid limited laboratory capacity in the state.

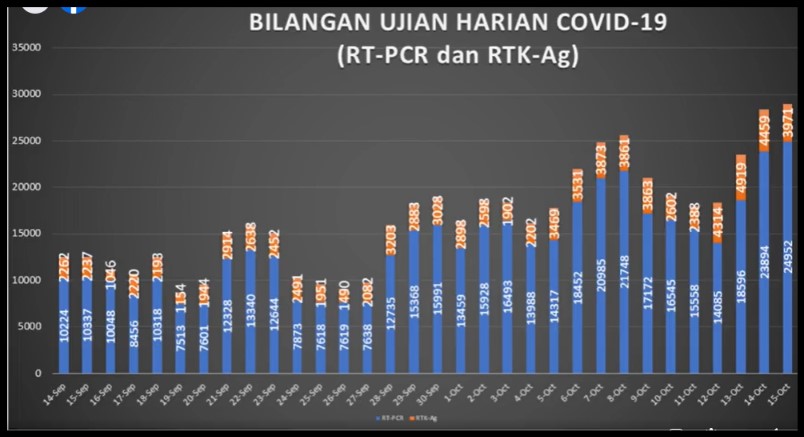

Despite increasing nationwide RT-PCR testing capacity to about 54,000 tests daily, MOH is still using only less than half of capacity. Only about 25,000 RT-PCR tests and nearly 4,000 antigen RTKs were run nationwide on October 15 (state breakdown, including for Sabah, was not provided). MOH simply said yesterday that 251,030 individuals in Sabah have been tested for Covid-19 since the start of the epidemic in Malaysia, with a 2.96 per cent positivity rate.

It would be more helpful to reveal the number of tests run and individuals tested – along with the positivity rate, broken down by district – in the current Covid-19 outbreak in Sabah, perhaps from September 1, when the index cases of the Benteng LD cluster were first discovered, rather than from the beginning of time of the pandemic. Singapore reports the average daily number of swabs tested over the past week.

Sabah had an estimated 3.9 million-strong population as of last year. How many Sabah residents were tested in the past six weeks? A Sabahan who tested negative for Covid-19 in June or July may have contracted coronavirus during the current outbreak.

Why can’t MOH ramp up antigen RTK testing in Sabah? Sending Sabah 100,000 antigen RTK for use in this whole month (covering just 2.7 per cent of Sabah’s population) only equates to some 3,333 tests a day. Dr Amar recommends running 30,000 to 50,000 antigen RTK in Sabah daily.

Antigen RTK can be done at the point of care and yields results in minutes; plus, they’re much cheaper than RT-PCR tests. Testing booths can be set up in common areas throughout Sabah so that they are easily accessible. Private general practitioner (GP) clinics can also help with rapid antigen testing in Sabah.

Rapid antigen tests are less accurate than RT-PCR tests (false negatives may occur 15 per cent of the time), but the objective is to quickly identify as many positive cases as possible so that they can be immediately isolated in quarantine centres.

Home quarantine is not suitable because one can still infect their household in close proximity, especially if one does not live in a large home with multiple bedrooms. RT-PCR tests can be done later to diagnose these people in quarantine.

Even if their RT-PCR test results take days to come back, at least they will be under medical supervision and have access to treatment should symptoms develop while waiting for their Covid-19 diagnosis. This may reduce the Covid-19 fatality rate in Sabah, as people will enter the public health care system at a much earlier stage of the disease.

The key to combating the Covid-19 outbreak in Sabah – which appears to have nearly overwhelmed the state’s under-funded, under-staffed, and under-resourced public health care system – is to catch cases early so that they infect fewer people and have higher chances of survival.

Running tens of thousands of antigen RTK daily in Sabah may yield very high (real-time) infection numbers exceeding 1,000 a day, but this should not scare the government. The more you test, the more you know. Mass testing will reveal locations of widespread outbreaks in Sabah that can direct more targeted public health responses.

It is only a problem, like what is happening now, when increasingly more Sabahans are turning up very sick and filling hospital beds rapidly, while other people reportedly wait nearly a week, unsupervised at home, for their test results. Despite 767 medical and public health workers being mobilised for the Sabah outbreak as of October 14, a large majority, 71 per cent, were from the state itself, while just 223 staff were from outside Sabah.

There are also reports of Sabah frontliners being told not to highlight problems or even requests for help on social media. This is not the way to handle a public health crisis. Government doctors should be allowed to speak freely, without sanction, especially when they’re putting their own lives on the line to protect the people.

Lawmakers and ordinary Malaysian citizens from outside Sabah cannot make appropriate public policies or offer assistance if they don’t know the true picture, amid poor media coverage during a lockdown in the state.

Sabah’s outbreak is nothing like the early waves of Covid-19 in Malaysia.

The government cannot rely on the same strategies it used previously that lulled us into a false sense of security, as we believed in our own hype and prematurely celebrated unrealistic “successes” of single-digit and even zero daily infections.

Yet, we see the same mistakes being repeated now, during a very real epidemic that threatens to drown the poorest state in the country. There is the same reluctance to make testing more inclusive, the reliance on lockdowns as blunt tools, and confusing lockdown rules that literally change with each press conference every day.

Instead of focusing our attention on Sabah, the government imposes a two-week Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO) on the Klang Valley, which may even be tightened further, despite the relatively flat epidemiological curves of Selangor and Kuala Lumpur compared to Sabah. The government doesn’t even see the need to reopen the MAEPS low-risk quarantine centre in Selangor at this point, which indicates that the health care system in the country’s most developed state and the capital city is well-prepared for a rise in Covid-19 cases.

A lockdown is not meant to eliminate Covid-19 transmission. As special envoy of the WHO director-general on Covid-19, Dr David Nabarro, says, lockdowns just “freeze the virus in pace” so that we have enough time to build up the capability of public health services.

Even in Sabah, whose lockdown is needed to curb the outbreak, the government must appreciate that the CMCO has far more severe effects on poor residents who live on daily wages, compared to white-collar workers in the Klang Valley, and hence, should tailor welfare assistance and public health strategies accordingly.

Working Malaysians sacrificed their livelihoods for seven entire weeks during the strict MCO from March to May. We all made this sacrifice — at the cost of job losses and pay cuts — to give our health care system enough time to build up capacity to deal with a virus we had never seen before.

But, nine months into the pandemic, if the government is saying that we still need lockdowns in areas without a surge of Covid-19 cases, then it appears that our sacrifices during the MCO were in vain, because the government clearly didn’t use the months we painstakingly gave them to boost health care capacity. Worse still, it appears that we had forgotten Sabah, the same state that previously saw a return of polio.

There is no need to play a blame game, sure. We can forgive past mistakes. But there is a definite need to change public health strategies and to improve transparency in the Sabah Covid-19 response. We will fail collectively as a nation if we can’t come up with the right solutions because we don’t know what the real problem is.

Boo Su-Lyn is CodeBlue editor-in-chief. She is a libertarian, or classical liberal, who believes in minimal state intervention in the economy and socio-political issues.