There was no knowledge about the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes Covid-19, when it announced itself to the world in January 2020. Since then, much has been learnt about the virus and the disease it causes although there is still much that is unknown.

The response of governments to the pandemic varied. The China government quarantined Hebei and instituted widespread testing, aggressive contact tracing, isolation of positive cases and population surveillance rapidly. South Korea instituted border control, physical distancing, rapid and widespread testing, aggressive contact tracing and isolation of positive cases, all of which were based on information technology.

South Korea and Japan did not institute lockdowns. Taiwan instituted border control, active case detection, widespread testing, and home quarantine for positive cases, with integration of any travel history with national health insurance records. Hong Kong instituted border control, physical distancing, high volume testing, aggressive contact tracing and quarantine centres. Taiwan and Hong Kong acted swiftly and opted for more strategic lockdowns which have allowed them to carefully reopen society.

Lockdowns are restrictions of movement, work, businesses, gatherings, education, and general activities.

When there was little or no knowledge of Covid-19, lockdown was considered an appropriate measure. The public health objective then was to prevent spread and deaths in the population, as well as to buy time for health care systems to prepare to deal with the disease.

Malaysia implemented the Movement Control Order (“MCO”) nationwide on 18 March which was extended till 12 May. The restrictions were eased on 4 May 2020 under a Conditional MCO (“CMCO”). However, some areas with high numbers of positive cases were subjected to more restrictive measures under the Enhanced MCO (“EMCO”) or Semi-Enhanced MCO (“SEMCO”).

No mention has been made whether the harms of lockdowns were factored into the decision-making then.

However, is it still an appropriate response to spikes at the current level of knowledge of the behaviour of the virus? Should not the harms of lockdowns be considered as Covid-19 has changed many of the social, economic, environmental and health care determinants of health?

Economic Damage

The economic damage from the MCO and its sequelae are well known. Data on the contraction of the economy, business closures and increasing unemployment are well documented.

The International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) found that lockdowns contributed to a global economic recession that affected vulnerable populations disproportionately. It also found that the damage to the economy was largely driven by people “voluntarily refraining” from social interactions out of a fear of contracting Covid-19.

The United Nations Population Fund (“UNFPA”) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (“UNICEF”) studied the effects of the MCO between 18 March and 13 May 2020 on 500 families with children in Kuala Lumpur’s low-cost flats. The unemployment rate in September 2020 remained troubling in which 1 out of 3 adults were unemployed; 1 out of every 3 heads of households with disabilities were not working; and among their household members, 60% were unemployed.

The unemployment rate for female heads of households was also relatively high compared to the national average, with 20% of their household members not working. “The COVID-19 crisis has pushed more families into poverty. The poverty rate in the community is higher than last year, with 1 in 2 of the families now living in absolute poverty, and it is slightly higher among children. In relative terms, 97% of the children and 100% of households with disabilities live in relative poverty.

“A sizeable number of workers remain unprotected. About 45 per cent of those currently working do not have an account with the Employment Provident Fund (EPF) or Social Security Organisation (SOCSO), and the figure is higher among working female heads of households (51%) and household heads with disabilities (73%).”

Some people can work from home. Many others cannot, especially those providing certain services.

Many face perils in their employment and low income. Business closures due to CMCO requirements or loss of business affect those employed in them. Many are daily paid or self-employed. They can lose all or part of their income. School closures require many to provide care to their children at home, thereby affecting their efficiency and effectiveness. This affects the low-income group and single-parent families more than others.

Although the impact of the MCO and its variants may be temporary, many do not have the safety net of savings. Low-wage workers, whose daily income determines their ability to survive, are at the highest risk of health problems arising from the economic stagnation.

The association between income and health is well recognised. Income permits purchase of the necessities of life, avoids harmful exposures, and promotes psychological well-being, participation in the activities of daily living and access to health and health care resources. The disadvantaged in society are affected disproportionately when there are total or partial lockdowns.

Health Harms

The effects of lockdowns on health can be direct, indirect or both. Social isolation and loneliness have impacted on the wellbeing for many. The stressors in lockdown include risk of infection, fear of infection or losing loved ones, and fear of financial hardship.

A review of the psychological impact of quarantine (lockdown) in The Lancet on 26 February 2020 reported that people who are quarantined are very likely to develop a wide range of symptoms of psychological stress and disorder. They included low mood, insomnia, stress, anxiety, anger, irritability, emotional exhaustion, depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Low mood and irritability were very common.

A national sample of 3,077 United Kingdom adults surveyed over three blocks of time between 31 March and 11 May 2020 reported that suicidal thoughts increased from 8.2% to 9.8%. The rates were highest in young people (18 to 29 years), increasing from 12.5% to 14.4%. One in four respondents (26.1%) experienced moderate to severe depression symptoms. Young people, women, those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds, and those with pre-existing mental health problems had the worst mental health outcomes.

A study of the psychological impact of Covid-19 and lockdown on 983 university students in Malaysia reported that 20.4%, 6.6%, and 2.8% experienced minimal to moderate, marked to severe, and most extreme levels of anxiety. The factors that were significantly associated with higher levels of anxiety were the female gender, age below 18 years, pre-university level of education, ages 19 to 25 years, management studies and staying alone. The main stressors included financial constraints, remote online learning, and uncertainty about the future with regard to academic performance and career prospects.

It is pertinent to remember that a study of the long-term effects of quarantine during the SARS outbreak in 2003 among health care workers reported a long-term risk for alcohol abuse, self-medication and long-lasting “avoidance” behaviour, i.e. some hospital workers avoided being in close contact with patients by simply not showing up for work years after their quarantine.

Lockdowns have had significant major effects on childhood vaccination programmes, education, sexual and reproductive health services, food security, poverty, maternal and under-five mortality, and infectious disease mortality.

Home quarantines or isolation have increased child abuse and domestic violence rates. Reports from Hubei in China, Singapore, France, Argentina and many cities in the United States have shown a substantial increase in domestic violence during lockdowns.

The harms from lockdowns also include its effects on health care delivery and access to health care.

In developed economies, it has impacted on consultations at emergency and primary care units for acute conditions like myocardial infarction and stroke, elective surgery, cancer diagnosis and treatment, intimate partner violence (see here and here), deaths of despair, and mental health.

Excess deaths capture both the direct and indirect effects of the pandemic. A estimate of the all-cause mortality effect of the pandemic for 21 industrialised countries reported that from mid-February through May this year, 206,000 more people died in these countries than would have had the pandemic not occurred.

A study conducted by the College of Surgeons of the Academy of Medicine of Malaysia reported on 3 July that 70% of scheduled medical operations in Malaysia were cancelled as a result of Covid-19. The SARS-CoV-2 Surgical Collaborative study with the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom reported that the most affected procedures were those for benign diseases (81.5%), followed by oncologic surgery (41%) and obstetric procedures (26.1%).

Delays in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer leads to progression of the cancer, thereby affecting patients’ survival. A review of the impact of the MCO on urology services at Hospital Serdang and Hospital Universiti Putra Malaysia reported that within 1.5 months of the start of the MCO on 18 March, urology services lost approximately 240 hours of day-care procedure and 180 hours of elective operating time, and about 1,560 clinic appointments to 1 to 6 months later.

There is increasing evidence to suggest that children and young people may be affected most by physical distancing and lockdown measures. There is a risk that school closures will exacerbate the existing inequalities in educational attainment. Surveys suggest that affluent households are more likely to be provided active assistance from schools, and that more hours a day are spent on home learning.

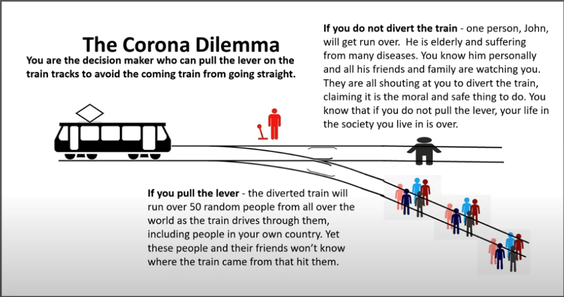

Paul Frijters, a welfare economist at the London School of Economics, asked the world, in March 2020, to consider The Corona Dilemma modelled on the trolley problem in ethics and psychology. He wrote “…the trade-off that has faced humanity over the coronavirus, where the options represent letting the virus rage unchecked (the train drives straight) or put whole countries into isolation, destroying many international industries and thus affecting the livelihoods of billions, which through reduced government services and general prosperity will cost tens of millions of lives (the diverted train).”

The majority of the world’s decision makers, including Malaysia, pulled the lever and the unintended health consequences of these measures were left out in modelling or policy.

First Do No Harm

The axiom “Primum non nocere” which is Latin for “First do no harm” has guided doctors and other health care professionals since time immemorial. Its application to public health means that the positive outcomes of public health interventions need to outweigh any negative effects. As such, it is not simply to consider the lives that may be saved by the efforts to limit SARS-CoV-2 spread, but more importantly, to consider the total number of lives saved and lost as a result of the pandemic and the responses to it.

The interventions to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 also have negative direct and indirect effects on health.

Despite the increasing evidence on the unintended, adverse effects of interventions like lockdown measures and physical distancing, there are few signs that policy decisions have been informed by a serious assessment and weighing of their harms on health.

Instead, the response to the current spike of cases in Malaysia have been another pulling of the lever in Paul Frijters infographic, with the implementation of CMCO on 14 October 2020, which has now been extended to 6 December 2020.

Carlo Caduff, of King’s College, London stated: “The failure to consider the impact of extreme measures that have become the norm in many places in the Covid‐19 pandemic has been stunning. The destruction of lives and livelihoods in the name of survival will haunt us for decades”.

David Staples, a Canadian infectious disease expert, stated on 21 October 2020 that lockdowns in Canada will cause 10 times more harm to human health than Covid-19 itself. Globally, “lockdowns will cause at least five times and, more likely, as much as 50 times more harm than benefit”.

Amesh Adalja, of Johns Hopkins Centre for Health Security in the United States, stated: “Lockdowns at this stage are…an ‘indication of policy failure, of not having driven the numbers down enough in the first wave and not putting in place a well-functioning test and trace system’”.

Fareed Zakaria, a newscaster and author, said on 27 October 2020: “Lockdowns are a sign you have failed…You are using a big blunt instrument, and you are crushing the economy.”

The World Health Organization’s position on lockdown has shifted from that in early 2020. Its envoy on Covid-19, David Nabarro, in an interview with The Spectator, on 9 October, stated: “We in the World Health Organization do not advocate lockdowns as the primary means of control of this virus…The only time we believe a lockdown is justified is to buy you time to reorganise, regroup, rebalance your resources; protect your health workers who are exhausted.

“Governments must make the most of the extra time granted by ‘lockdown’ measures by doing all they can to build their capacities to detect, isolate, test and care for all cases; trace and quarantine all contacts; engage, empower and enable populations to drive the societal response and more.”

Going Forward

China imposed one of the most severe public health restrictions in history, something most countries would be unlikely to replicate.

Others, like New Zealand, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore, acted swiftly by closing borders, imposing strict public health measures, and opted for shorter, strategic targeted lockdowns. South Korea and Japan did not lockdown at all and instead focused on testing, tracing, and isolation of cases to control the viral spread successfully.

On the other hand, Argentina’s lockdown, which is the world’s longest (since 20 March 2020) and stringent, has failed spectacularly (1.273 million Covid-19 cases as at 14 November 2020) and brought the country to the verge of economic collapse.

It is time to take a pause, re-calibrate Malaysia’s response to the true risk, make rational cost-benefit analyses of the trade-offs, and review the lockdown mentality, which is a simplistic and crude intervention, to say the least.

Covid-19 will be with us even when vaccination is available. Can the country’s economy and its population’s mental and physical health sustain protracted CMCOs on every occasion there is a spike? How long will the public tolerate the CMCOs? When will pandemic fatigue lead to pandemic anger and its attendant consequences?

There is an urgent need for the government to review its policies and strategies. In this respect, the appointment of an independent panel of experts will provide wider perspectives and options.

Dr Milton Lum is a past president of the Federation of Private Medical Practitioners Associations and the Malaysian Medical Association. The views expressed do not represent that of any organisation the writer is associated with. The information provided is for educational and communication purposes only and it should not be construed as personal medical advice. Information published in this article is not intended to replace, supplant or augment a consultation with a health professional regarding the reader’s own medical care.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.