There has been a surge of Covid-19 cases since mid-September 2020. The number of reported positive cases have trebled from 10,031 to 31,548 on 31 October.

It took 235 days to get from the first reported case on 25 January to cross 10,000 cases (10,031 reported on 16 September); 33 days to cross 20,000 cases (20,498 reported on 18 October); and 11 days to cross 30,000 cases (30,090 reported on 29 October).

The active cases increased 36.03 times from 279 on 1 September to 10,051 on 31 October.

After a lull from mid-June to mid-September, there is an awesome sense of déjà vu with the exponential increase in numbers of reported positive cases and deaths. Despite the lockdown with the Movement Control Order (“MCP”), physical distancing, wearing of face masks, handwashing and isolation from family and friends, the country appears to be back where it started.

Covid-19 And The Disadvantaged

Covid-19 has been described as a heat-seeking missile speeding towards the most vulnerable in society. The disadvantaged have been affected the most across different countries and within most countries. The rich in many countries have prospered with the pandemic, whilst the poor are at the abyss.

It is well documented that people in the lower socio-economic groups suffer more from infectious and non-communicable diseases compared to those who are better off.

Published reports from the United States and United Kingdom document a higher incidence of Covid-19 cases and deaths among the poorer segments of society, e.g. those in the poorer Bronx borough of New York City compared to the more affluent Manhattan borough. Similarly, the most deprived areas of Wales had a Covid-19 mortality rate that is nearly twice as high as that in the least deprived areas.

Sabah is one of the more deprived states of Malaysia. The health indicators of Sabah are not better or equivalent to that of the peninsular states. There are indications it is worse in various aspects with published reports of the impact of poverty on the health of its people. The resurgence of the polio outbreak in Sabah in early 2020 was an indicator of the weaknesses in Sabah’s health care.

Sabah’s health care delivery system lags behind that of the peninsular states because of various reasons, which include geography; infrastructure; limited financial and human resource allocation; and heath literacy.

The weaknesses in Sabah’s health care delivery system; and its proximity to and porous borders with Indonesia and the Philippines, both countries with the highest number of Covid-19 cases in ASEAN, had been the concern of many health care professionals since the outbreak began.

As such, Sabah’s spike was not unexpected by many health care professionals. The exponential increase in the reported cases and deaths in Sabah has exposed the weaknesses in its health care delivery system.

Sabah Covid-19 Spike

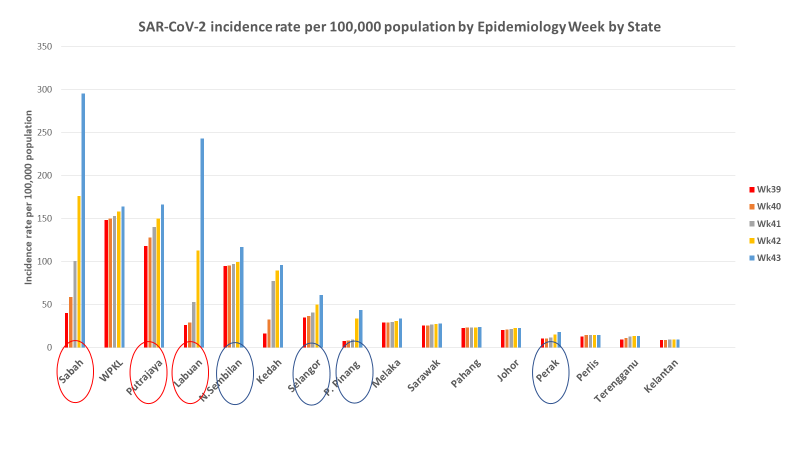

Sabah’s contribution to the Covid-19 increase in reported cases and deaths since mid-September was disproportionate to all the other states put together.

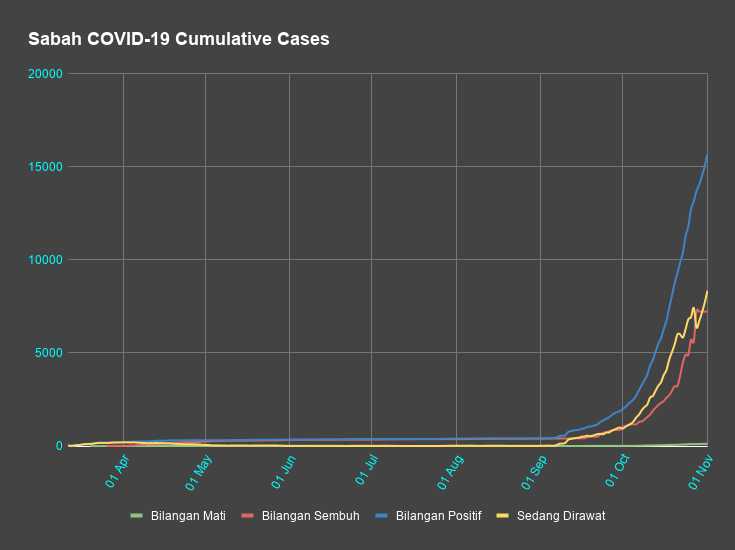

Data from the dashboard of the Sabah Covid-19 Command Centre recorded 15,048 cases on 31 October, with 7,225 discharged, 117 deaths, 1,651 quarantined and 28,950 on home quarantine (Figures 1 & 2). Accessed 31 October 2020).

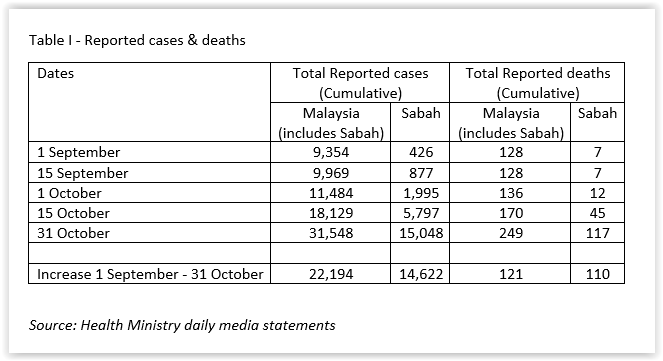

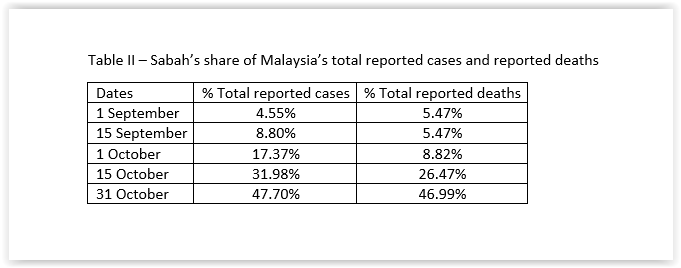

There was a marked increase in the number of reported cases and deaths in September and October. The increase of 14,622 reported cases in Sabah accounted for 65.88% of the country’s increase (which includes Sabah cases). The increase of 110 reported deaths in Sabah accounted for 90.90% of the country’s increase during the same period. (Table I).

Since 1 September, Sabah’s share of the total reported cases in Malaysia (which includes Sabah’s data) increased by 10.48 times to 47.70% on 31 October. At the same time, its deaths increased by 8.59 times to 46.99% of Malaysia’s total reported deaths. (Table II)

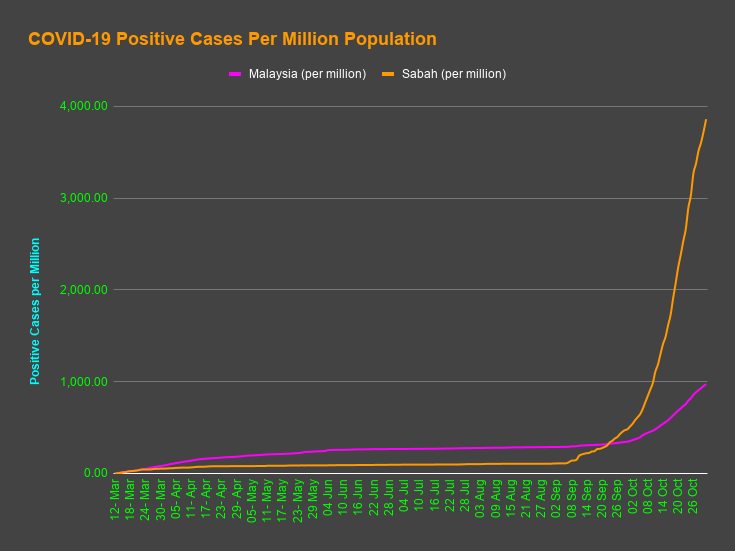

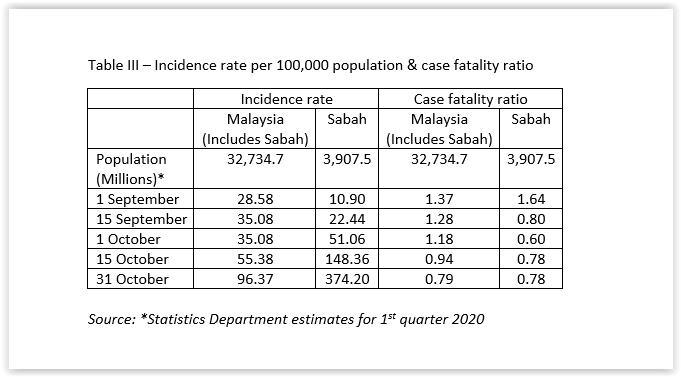

Since 1 September, the incidence rate per 100,000 population increased by 3.37 times for Malaysia (which includes Sabah data), with an increase of 34.33 times for Sabah, which is more than 10 times the national figure. The case fatality ratio has been falling for Malaysia (which includes Sabah data), notwithstanding the increase in reported positive cases. However, for Sabah, it decreased until 1 October, after which it increased. (Table III & Figure 2)

The Health Ministry stated, on 28 October, that of the 110 deaths then, 35 in Sabah had died prior to admission to hospital i.e. were brought in dead (“BID”). One has to try hard to find a country or region in which a third or more of the Covid-19 deaths were BID.

The reasons for Covid-19 cases BID in Sabah could include under-screening; under-diagnosis; co-morbidities like diabetes, hypertension etc; problems accessing health care facilities; instructions to positive cases to stay at home because hospital beds are full and sudden deterioration in these patients.

Tipping Point

The Oxford Dictionary defines the tipping point as “the point at which a series of small changes or incidents becomes significant enough to cause a larger, more important change.”

Malcolm Gladwell, in his groundbreaking 2000 book, “The Tipping Point” defined it as “the moment at which big changes follow seemingly small events.” He called the tipping point “a place where the unexpected becomes expected, where radical change is more than a possibility. It is — contrary to all our expectations — a certainty.”

The Covid-19 pandemic has illustrated this very well. Health care systems globally are increasingly challenged with many overwhelmed and struggling with the pandemic. The deluge of infected patients and suspects are stretching many health care systems beyond their capacity.

Sabah Health Care At Tipping Point

On 30 September, the Health Ministry claimed that Covid-19 was spreading faster in Selangor than in Sabah with a Rt of 1.95 in the former, compared to Sabah’s Rt which had stabilised at 1.29. The Health Ministry uses Rt as an indicator of the rapidity of Covid-19 spread.

On 3 October, the Health Ministry predicted that the rising cases would climb for another two to seven days. Subsequent events proved otherwise. The incidence rate has been highest in Sabah, followed by Labuan, Putrajaya and Kuala Lumpur recently.

Health care professionals in Sabah have described anonymously their personal experiences amidst the critical situation there. The anonymity was necessitated by the Health Ministry’s gag conditions in their terms and conditions of service. However, on 30 October, a doctor from the Medical Department in Tawau Hospital described the difficulties and fears faced by them.

Patients and their families have also taken to social media to express their anguish and difficulties. In particular, positive cases had to wait at home for days, some up to ten, before they could get admission to treatment centres.

On 18 October 2020, Sabah’s state Local Government and Housing Minister Masidi Manjun stated there was a backlog of 18,000 test results. The Health Ministry admitted that its testing capacity in Sabah was limited to 2,500 to 3,000 tests daily, although the Health Ministry had stated that the national testing capacity was more than 50,000 tests daily.

The Health Ministry had to deal with the additional tests required in Sabah by air transport to its laboratories in the Peninsula; outsourcing them to private clinics and hospitals; and using rapid test kits recently.

Sabah’s testing capacity has been an issue since April with 700 to 800 tests daily then. Although health is a federal matter, the state government contributed to the situation then by sourcing the test kits from abroad. The-then Sabah Chief Minister had called on the Health Ministry, on 16 April, to establish laboratories in Sandakan and Tawau to test for Covid-19.

On 22 October, Masidi stated that some positive cases with manageable symptoms were treated with home quarantine with advice to adhere to standard operating procedures (“SOP”). It is pertinent to note that as at the time of writing, on 2 November, there had been no mention of home treatment in the Health Ministry’s SOP for positive cases.

On 23 October, the Health Ministry refuted Masidi’s statement and stated that all positive cases were treated in hospitals or quarantine centres, of which there was 36% occupancy of the 12,557 beds available then.

On 26 October, the Health Ministry stated that Covid-19 bed occupancy rate in hospitals was 52%, intensive care unit (ICU) bed occupancy rate was 69%, and bed occupancy rate in low-risk quarantine and treatment centres was 28%. It also predicted that the outbreak in Sabah would be contained in four weeks.

The Malaysian Medical Association’s call on the Health Ministry not to provide aggregate data, but instead provide data on the utilisation of individual hospitals and quarantine centres to avoid misperceptions on 27 October has yet to elicit a response from the Ministry.

Masidi admitted, on 28 October, that he did not have statistics on the bed occupancy of individual hospitals and quarantine centres or the available beds for Covid-19 patients. His frankness was laudable. However, it exposed a serious gap in the sharing of information and coordination between the Health Ministry and the state government.

A news portal reported the Health Ministry’s admission of delay in getting positive cases from their homes to treatment centres, with some patients waiting at home for up to ten days!

The gut reaction to any problem is to denial. Another reaction is to castigate the messenger(s). Neither of these approaches, which has been reported to have been used, will contribute an iota towards containing the virus.

Winston Churchill’s advice is still relevant today:

“Criticism may not be agreeable, but it is necessary. It fulfils the same function as pain in the human body. It calls attention to an unhealthy state of things.”

Winston Churchill, New Statesman interview, 7 January 1939

Experts have even opined that the Sabah health care system may collapse. The Health Ministry has acted to increase the capacity of its hospitals, including field hospitals, and quarantine centres.

However, there has been no reports of similar increase in the capacity of public health measures. If there is no equal or limited focus on public health programmes, the whole health care delivery system can collapse, however well-resourced hospitals are, with dreadful consequences.

Whether palatable or not, the indications are that Covid-19 has put Sabah’s health care delivery system at the tipping point.

Last but not least, pray for Sabah.

Dr Milton Lum is a past president of the Federation of Private Medical Practitioners Associations and the Malaysian Medical Association. The views expressed do not represent that of any organisation the writer is associated with. The information provided is for educational and communication purposes only and it should not be construed as personal medical advice. Information published in this article is not intended to replace, supplant or augment a consultation with a health professional regarding the reader’s own medical care.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.