From An Over-Performer To An Underperformer In Child Health

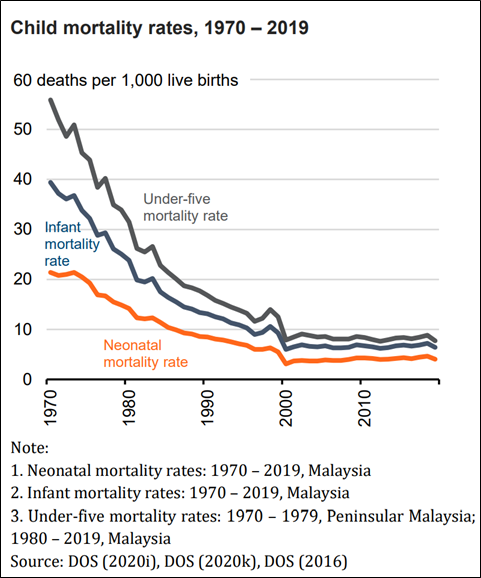

Although in the 20th century, Malaysia, an ‘Asian tiger’, used to be an over-performer in the arena of child health, the country’s performance in recent years has been less flattering.

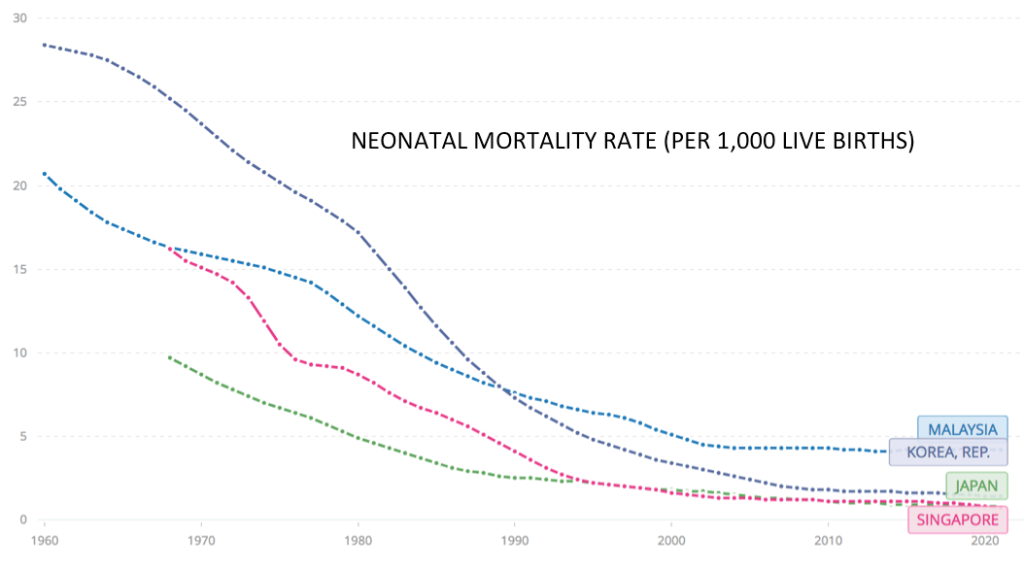

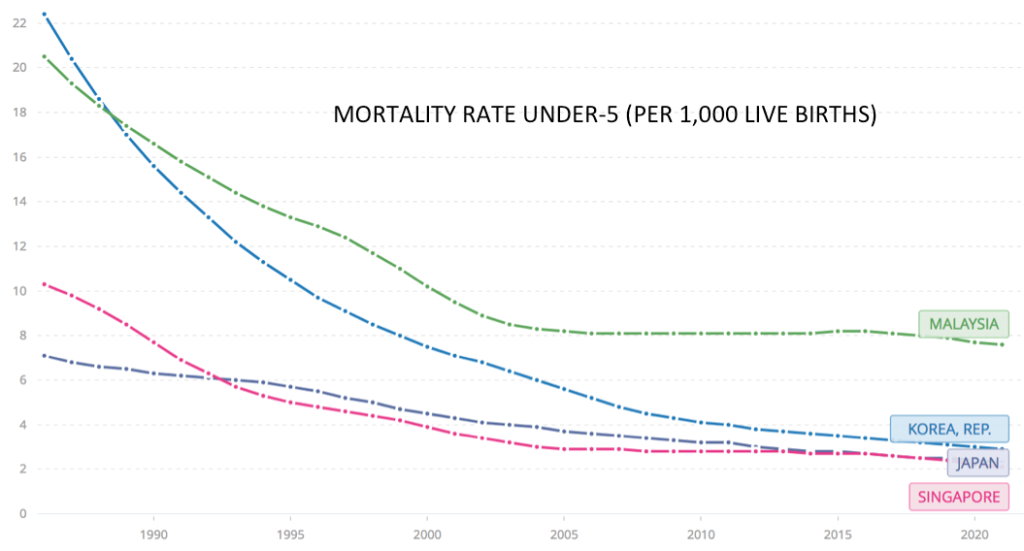

Critical indicators for child health have stagnated, and deaths among newborns, infants, and children have made no discernible progress during the last two decades. Malaysia is increasingly trailing behind comparator countries such as South Korea, Japan, Singapore, and Taiwan.

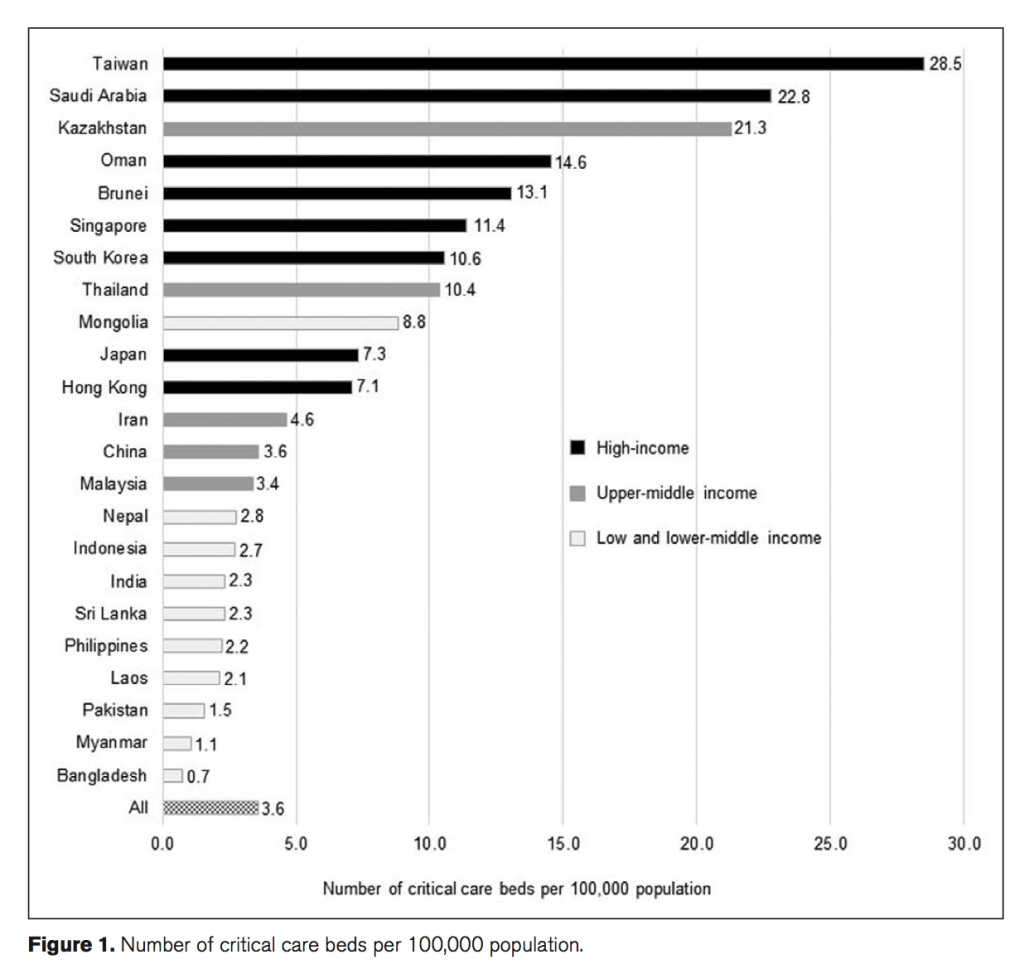

The low numbers of intensive care facilities per capita is a pervasive problem in Ministry of Health (MOH) critical care services.

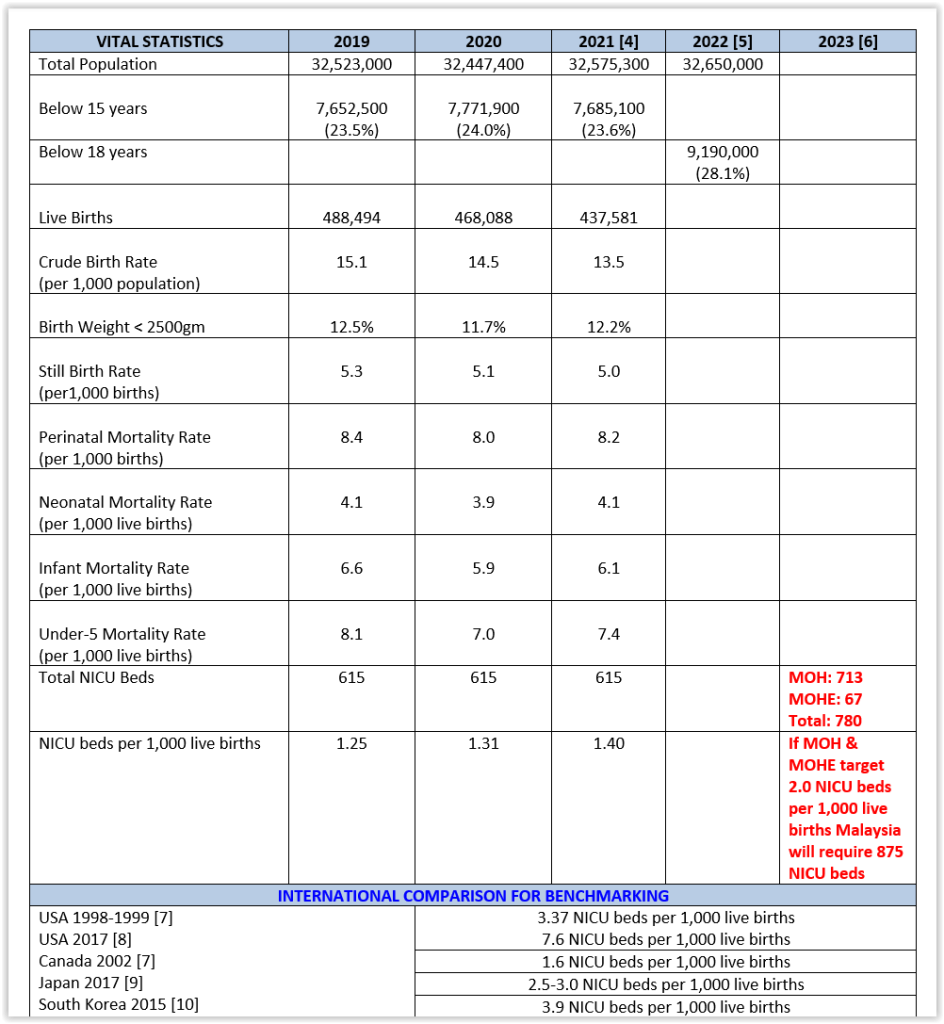

One of the critical success factors (CSF) of health care for children is the availability and accessibility to neonatal intensive care, which has been associated with significant improvements in the survival rates of newborns, especially those with low birth weight or gestational age.

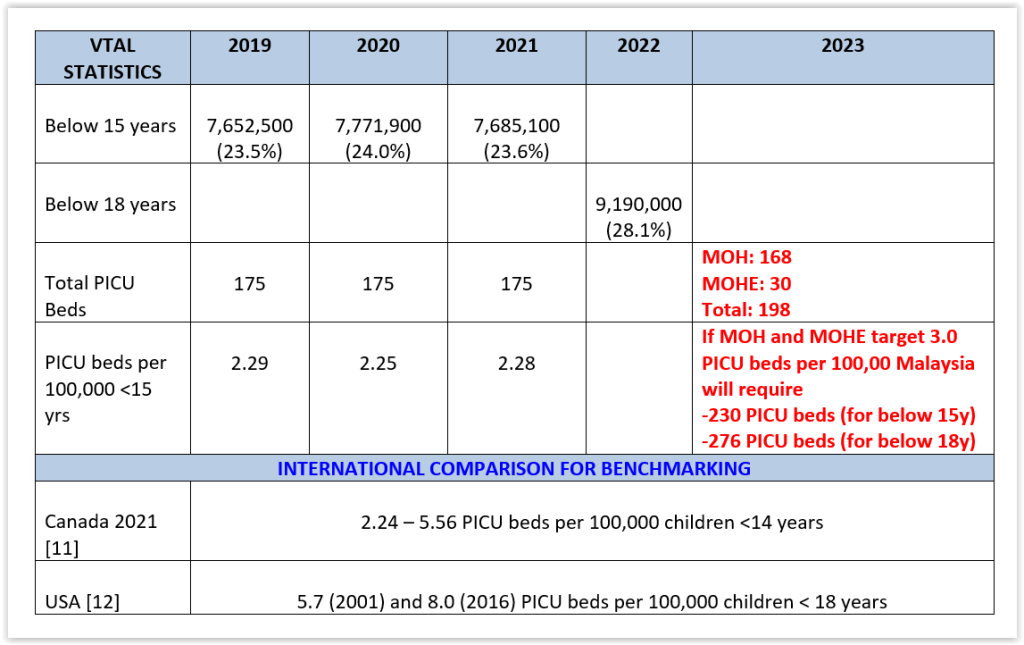

The flattening of our child mortality rates in the 2000s is partly, yet significantly, contributed by the lack of NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) and PICU (paediatric intensive care unit) beds. Our intensive care norms are unfortunately stuck in a time warp, utilising the intensive care norms of the 20th century.

A conservative increase of intensive care norms to two NICU beds per 1,000 live births will require an additional 95 more NICU beds in 2024 in the MOH and the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE).

There are presently 74 NICU beds in the private health sector. In the spirit of public-private partnerships (PPP), these can be utilised by the MOH and MOHE to outsource neonatal intensive care services to private hospitals, considering that the NICUs in the public sector are virtually always full.

If this option is seriously considered, it must be budgeted for in the upcoming Budget 2024.

A nominal increase to three PICU beds per 100,000 children will require an additional:

- 32 PICU beds in 2024 for pediatric intensive care of children less than 15 years in the MOH and MOHE.

- 78 PICU beds in 2024 for pediatric intensive care of children less than 18 years in the MOH and MOHE.

There are only 11 PICUs in the private health care sector. There must be a genuine effort to boost the numbers of PICUs in the MOH and MOHE.

The provision of paediatric intensive care is likely responsible for a five-fold reduction in infant and child mortality rates.

Furthermore, centralised paediatric intensive care has been associated with a two-fold reduction in the length of stay in the intensive care unit and a 50 per cent reduction in mortality.

The increase in NICU and PICU beds needs to be in line with the corresponding step-down of the number of Special Care Nursery (SCN) and Pediatric High Dependency Unit (PHDU) beds in the MOH and MOHE.

Apart from the quantity of NICUs and PICUs, of equal importance is the need to ensure the development of high-quality intensive care services for children, which, among others, constitute the following characteristics and technologies:

- Regional neonatal and paediatric networks.

- Appropriate staffing levels of neonatologists, paediatric intensivists, intensive care nurses, etc., as laid down by the MOH and professional bodies.

- Training of more intensivists and intensive care nurses.

- Best practice guidelines and benchmarking exercises.

- Data sharing infrastructures.

- Communications and administration systems.

- Retrieval systems.

- A critical care ambience to embrace better family centred care.

A separate budget beyond that for paediatric departments needs to be provided to ensure delivery of optimal neonatal and paediatric intensive care services.

This is not too much of an ask in Budget 2024, for the protection and preservation of our children’s lives and to improve their long-term health prospects and quality of life.

It is indeed one of the true key performance indicators (KPI) of how authentic is our love for our children.

This article was written by:

- Dr Musa Mohd Nordin, past president, Perinatal Society Malaysia (PSM).

- Dr Selva Kumar Sivapunniam, president, Malaysian Paediatric Association.

- Dr Amar-Singh HSS, advisor, National Early Childhood Intervention Council (NECIC).

- Dr Tang Swee Fong, assistant secretary, Malaysian Society of Intensive Care (MSIC).

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.