KUALA LUMPUR, July 1 – When St John Ambulance of Malaysia (SJAM) extended an invite to CodeBlue to attend their free two-hour CPR+AED course last Sunday (June 26), there was no way I could say no.

At the editorial desk, we knew first aid was a necessary follow-up on our report headlined “Ipoh Teacher Dies In Ambulance Response That Allegedly Skipped CPR”, but personally, having some basic knowledge of first aid could mean the difference between life and death at home.

Of course, cardiac arrest can happen to any of us, anywhere, but for my 58-year-old father, the odds are pretty high. My father has a long history of heart attacks dating back to 1997, when he was just 33. He often suffers from angina – chest pains caused by reduced blood flow to the heart muscles – due to the abnormal size of his arteries.

Over the years, he has suffered numerous chest pains, made countless trips to the hospital, and been admitted at least 10 times for his heart problems. So, in our household, there is a reasonable chance of having to perform CPR, hence why I enrolled on SJAM’s short course.

The free two-hour CPR+AED course by SJAM covers cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and automated external defibrillator (AED) training. The course takes place every last Sunday of the month from 1pm to 3pm, at the SJAM National Headquarters in Kuala Lumpur. It usually caters to about 20-25 participants per session.

Upon arrival, participants are given the DRSABCD Action Plan card. DRSABCD stands for Danger, Response, Shout, Airway, Breathing, Compression, and Defibrillation – a simple seven-step plan used to assess if a person has a life-threatening condition and requires immediate first aid. Its convenient credit card size fits easily into a wallet for quick reference.

The course began with a brief introduction to the history of SJAM and the many different services they provide, including training, ambulance services, hemodialysis, nursing, and mobile clinics. Chew Hoong Ling, SJAM’s national staff officer for training, led the course.

Most participants had no experience in CPR, except for a few who came to refresh their CPR skills and knowledge. However, a significant number said they had prior experience calling the Malaysia Emergency Response Services (MERS) 999.

The course then proceeded to its syllabus: DRSABCD. These acronyms will be our mantra throughout the entire course – first, in theory, then via demonstration, and lastly, through practical training.

“If there’s anything you should remember from today, it’s this action plan,” Chew said.

DRSABCD – The ABCs Of First Aid

“D” is for danger. The first step in providing aid is to check for danger. This includes traffic, broken glass, fire, chemical spills, electricity, sharp edges, and unstable structures. You should ensure that the patient and everyone in the area are safe. If it’s safe, remove the danger or the patient.

You can also wear personal protective equipment (PPE), rubber gloves or masks, if available, to avoid contracting any disease from the patient.

“R” is for responsiveness. Once the danger is cleared, you can then check if the patient is responsive or unresponsive by tapping on their shoulders and loudly asking their name or “Are you okay?”.

“S” is for shout. If there is no response from the patient, you should shout for help and instruct people nearby to call for an ambulance while another gets an AED if the device is nearby.

AEDs are likely available in places where people congregate, such as malls, convention centres, airports, office towers, and places of worship. If there are no other bystanders, proceed to call 999 on your mobile.

“A” is for airway. If the victim is unconscious and unresponsive, place the patient on their back on a firm, flat surface. Typically, you would then check to ensure that the patient’s mouth and throat are clear by opening their airway using the head-tilt, chin-lift manoeuvre.

However, due to Covid-19, the current guideline is to cover the patient’s nose and mouth with a piece of cloth instead. This is in line with the European Resuscitation Council guidelines.

“B” is for breathing. Check if the patient is breathing abnormally or not breathing at all after 10 seconds by placing your hand on their stomach.

Participants at St John Ambulance of Malaysia (SJAM) were shown a 3D animation video demonstrating effective CPR. Video by Action First Aid, a training agency for first aid and defibrillators in Canada.

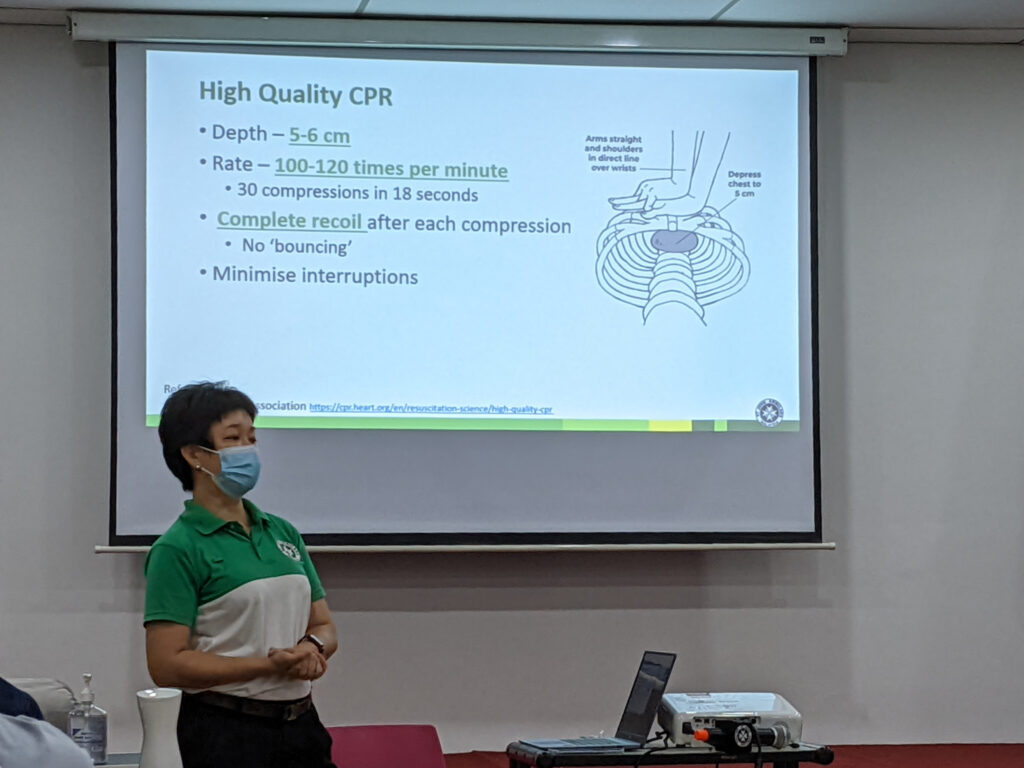

“C” is for compression or CPR. If the patient is not breathing, start chest compressions as soon as possible. To perform chest compressions, place the heel of one hand in the centre of the person’s chest. Then, place the other hand on top of the first hand and interlock your fingers.

Position yourself above the patient’s chest. Using your body weight and keeping your arms straight, press straight down on their chest by one-third (5-6 centimetres) of the chest depth. Release the pressure. Pressing down and releasing is one compression.

Push at a rate of 100 to 120 compressions a minute. A classic tip is to push to the beat of the Bee Gee’s song “Stayin’ Alive”. Other songs within range are Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust”, Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy”, and Beyonce’s ‘Crazy in Love’.

Repeat these compressions without giving breaths (hands-only CPR) until an ambulance arrives or as long as you can. Alternate if there are other individuals on site.

“D” is for defibrillation. Attach an AED to the patient if one is available and someone else can bring it.

When an AED is available, turn it on and follow the voice prompts. Remove all clothing covering the chest and attach the pads correctly. If necessary, wipe the chest dry.

Place one pad on the upper right side of the chest and the other pad on the lower left side of the chest. Prepare to let the AED analyse the heart’s rhythm.

Make sure no one touches the patient, and tell them to stay clear in a loud, commanding voice. The AED will determine if a shock is needed. Push the “shock” button to deliver the shock.

After the AED delivers the shock, or if no shock is advised, immediately start CPR, beginning with compressions.

Of Manikins And Machines

Once we familiarised ourselves with the action plan, in theory, it was time for a demonstration from one of SJAM’s trainers that day, Cheang Chee Kin.

Before the demonstration, Cheang sanitised and wiped down the entire manikin. He then physically demonstrated the DRSABCD as a whole action plan, including how to operate the AED, as we observed.

The trainers then divided participants into eight groups of two to three. Each group had their bluetooth-enabled manikin to practice with.

Before the physical activity started, we were told to download the ‘QCPR Training’ app that allowed our phones to connect to the manikin via bluetooth. The app provides real-time indicators of the depth and speed of the chest compressions performed on the connected manikin and measures the overall quality of the CPR.

Individuals in each group took turns to play different roles – the CPR provider, the person calling 999, and the person in charge of AED.

We first took turns to practice chest compressions on the manikin without the AED. Then, we were given a few minutes each to practice the DRSABCD action plan, minus the “D”. During these first few rounds, many of us were excited and energetic.

We then proceeded to practice with the AED. The chest compressions continued, though many were starting to wear out, as we each did dry runs using the AED – switching the device on, following its voice prompts, removing the clothing that’s covering the manikin’s chest, attaching the pads, and pushing the “shock” button.

Individuals in each group continued to alternate to play different roles.

By 3pm, we had concluded the session. Each group helped to clean up and pack up the manikin before we returned to our seats for a short debrief with Chew.

“How do you feel? It’s tiring, right? And that’s just a few minutes. How long do you think the ambulance will take to arrive? 20 minutes? 40 minutes? Can you continue with the CPR that long?” Chew asked. Participants either shook their heads or were simply out of breath.

In Malaysia, the Ministry of Health’s (MOH) target emergency response time is 15 minutes. However, the international recommendation for ambulance response time to medical emergencies is eight minutes for at least 90 per cent of ambulance calls.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 90 per cent of people with cardiac arrest outside the hospital die, but early CPR can double or triple the survival odds.

Chew said giving first aid is about trying to keep someone alive until professional help arrives. CodeBlue previously reported public emergency specialists saying that bystanders should help perform CPR to increase the chances of surviving cardiac arrest.