KUALA LUMPUR, June 28 – Having a bystander perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) before a paramedic team arrives can help increase the chances of surviving cardiac arrest, two emergency specialists at the Ministry of Health (MOH) said.

Dr Ammar (pseudonym), who handles critical care patients at a public hospital in Selangor, told CodeBlue that the most likely outcome for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) cases is that the victim “would have been dead by the time paramedics arrive.”

Another government emergency doctor, Dr Haris (pseudonym), who also serves at a hospital in the Klang Valley, said it is “impossible” for an ambulance, even in advanced countries, to arrive at the scene within five minutes, with brain death setting in at four minutes.

Both physicians requested anonymity due to a gag order on civil servants.

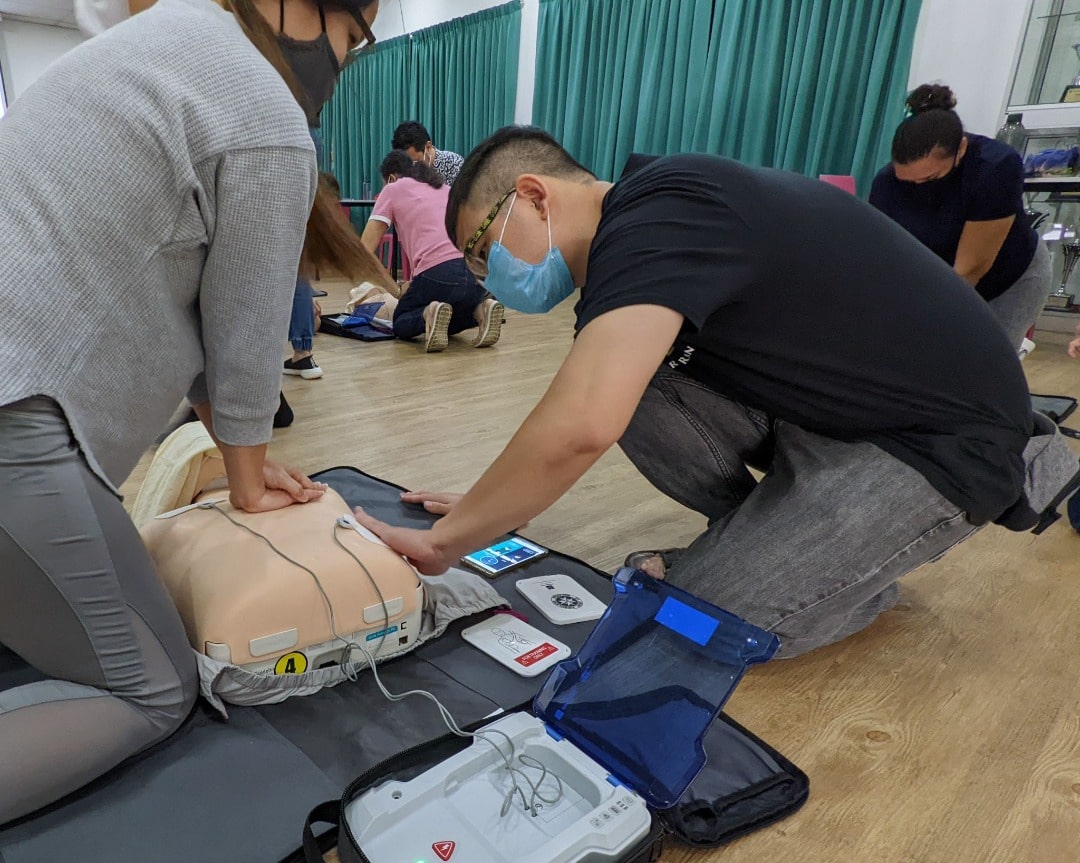

Cardiac arrest happens when one’s heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops pumping, which causes blood to stop flowing to the brain and other vital organs. CPR is an emergency lifesaving procedure performed when the heart stops beating. Health care providers and those trained perform conventional CPR using chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing, while the general public or bystanders are recommended to perform compression-only or hands-only CPR.

Brain death is the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, responsible for regulating the body’s automatic functions such as breathing, heartbeat, blood pressure, and swallowing.

In the United Kingdom, a person who is brain dead is “legally confirmed” as dead as the person has no chances of recovery due to their body’s inability to survive without artificial life support, according to the National Health Service (NHS).

“Thus, CPR by bystanders is crucial for a chance of life. If bystanders attempt CPR while an ambulance arrives, the team will continue the effort and bring the patient to the hospital,” Dr Haris said. “With no CPR done beyond 15 minutes, the chance of recovery is nil.”

CodeBlue reported last Wednesday complaints of negligence by Dr Thiru Terpari @ Thirupathy, a medical officer at Raja Permaisuri Bainun Hospital (HRPB), accusing the MOH facility’s ambulance response team of allowing his brother, Kumaraveloo, to die last April 13 in Ipoh, Perak, by leaving him in his car and by withholding CPR intervention from the St Michael’s Institution teacher.

Bystanders Can Help Cardiac Arrest Victims Survive

With a target emergency response time of 15 minutes for a public ambulance in Malaysia, the life of a person with cardiac arrest often depends on someone who knows CPR and knows how to use an automated external defibrillator (AED), if the device is available nearby. An AED device delivers a jolt of electricity to get the heart beating again.

But CPR awareness and training remains poor in Malaysia, which is why at any MERS 999 call centre, there is a clear protocol to advise on CPR, Dr Haris said. “These are embedded in the system and it mirrors the American emergency medical services (EMS) protocol.”

The MERS 999 is an integrated, but tiered, system combining the emergency services of five agencies, consisting of the Royal Malaysia Police, the Fire and Rescue Department of Malaysia, the MOH, the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency, and the Department of Civil Defence.

Alternatively, 112 is the standard emergency number globally which could be made from a mobile phone, regardless whether the mobile phone has credit, is barred, or locked. All 112 calls would be redirected to 999 response centres.

According to a 2015 article in The Star, citing MERS 999 project director Rozinah Anas, the calls are answered by professional emergency officers (PEO) within 10 seconds. The PEO will ask the caller general questions on the type of emergency, location of the incident, and contact number to verify the legitimacy of the call.

In another article by The Borneo Post published in May this year, it was detailed that if an ambulance is required, MERS 999 will divert the call to the Medical Emergency Coordination Centre (MECC) of the respective state, who will then enquire about the caller’s basic information, contact number, address, and the nature of emergency.

It is assumed that the call will then be directed to a public hospital ambulance service or auxiliary services such as MRCS and SJAM.

According to the Malaysian Association of Medical Assistants’ (MAMA) “tips” for 999 ambulance calls, assuming that the call is directed to a government hospital’s ambulance service, an officer will try and assist the caller by providing first-aid instructions that can be performed while waiting for an ambulance to arrive.

It was noted in MAMA’s Facebook post that the official on the phone will not be the same as the prehospital care unit officer heading to the scene. The public is also advised not to end the call until they are told to do so.

An example of a 999 call transcript involving a cardiac arrest case in the UK was published by The Guardian in 2008.

Dr Haris said bystanders must initiate CPR early while an ambulance arrives for the victim to have a chance of survival. “The ambulance team will then continue the effort as there would still be a chance of recovery,” he said.

Dr Ammar added that in cases of cardiac arrest, the caller will be asked to check for signs of life and will be guided to do CPR before paramedics arrive.

“The important thing here is that the public has a role and calling 999 is a good move. At least they called and didn’t run away from the scene. There are Good Samaritans out there who would help,” Dr Ammar said, referring to Kumaraveloo’s case.

“But most people do not want to take that extra responsibility to wait and to give statements, which will help in any incident that occurs. So, it’s not easy to help people.”

Why Call 999 If The Ambulance Will Arrive Late?

Dr Haris said it is wrong to presume that first responders will not do anything once they arrive: “The ambulance team will check, regardless of time, the condition of the victim with equipment. If the patient is still warm, and the event still early, the team will still do CPR and this is the practice in most cases.”

He said most cardiac arrest victims who survive – whether in the US, the UK, or Japan – are largely because bystanders initiate CPR early. “The ambulance team then has a chance to continue. Nevertheless, the team will still check the heart and if there is any rhythm at all, despite it beyond 15 minutes, and will continue with resuscitation,” Dr Haris said.

Dr Ammar explained that early CPR by a bystander constitutes basic life support (BLS), which covers initial resuscitation efforts such as CPR and AED usage, while the paramedic team can do both BLS and advanced life support (ALS).

“Basic life support is what we refer to as CPR, first aid basic life support, which includes CPR – that is the fundamental of resuscitation.

“ALS will provide better care to the patient where there is an indication to provide it. So, the paramedics that arrive can do intubation to provide more oxygen to the patient, and they can give drugs, if needed, to try and kickstart the heart.

“If they see signs that allow them to shock the patient, they will shock the patient because they have a defibrillator on board. So, there are other items that we can use to kickstart the heart rather than just chest compressions, but that chest compressions will continue,” Dr Ammar said.

Paramedics To Check For Signs Of Life Upon Arrival

Dr Haris said a paramedic will typically look for signs of life, such as breathing or gasping. With no signs of life, the patient’s body temperature can be felt by hand, pupils assessed (if fixed and dilated), the joints moved for stiffness – all of which are clinical examinations.

“They also have thermometers that they can use, but clinical examinations are often enough to recognise death,” Dr Haris said. He added that while paramedics will not know the exact time a patient’s heart stopped beating, patients, whose heart was still beating just minutes before paramedics arrive to attach monitor leads to their chest, would still be warm.

“Typically, such patients would still be warm. There would not be any stiffness of the joint. In such cases, they would provide CPR, and this is in most cases. In this case (Kumaraveloo), there was stiffness felt by the paramedic, apart from the skin already cold,” Dr Haris claimed.

The MOH has not publicly released any details about HRPB’s emergency medical response in Kumaraveloo’s case, save a statement from the HRPB director who claimed that the MA from the ambulance team had followed protocol, according to the public hospital’s internal inquiry. The MA’s prehospital care form, as sighted by CodeBlue, did not mention body stiffness or mark rigor mortis, only algor mortis.

Algor mortis is the reduction of body temperature until it reaches the ambient temperature. Algor mortis typically starts about 30 minutes after death and can continue up to 48 hours, though signs could appear before the suggested timing, Dr Haris said.

Rigor mortis, on the other hand, is the stiffening of body muscles due to chemical changes and starts as early as two hours of death. A person having algor mortis indicates that brain death has set in and the body cannot regulate its temperature anymore.

“In this case, the documentation was ‘algor mortis’, indicating that the patient already had brain death and this was confirmed with the machine that confirmed no cardiac activity. The chance of recovery for the patient was pretty poor,” Dr Haris said, referring to Kumaraveloo’s case.

“The ambulance team in Malaysia, in most cases, will still provide CPR and subsequent care regardless of time when called. In this case, there was stiffening and coldness noted by the responder and the cardiac machine showed no heart activity.”

Dr Haris (pseudonym), emergency specialist at a public hospital in the Klang Valley

According to the Academy of Medicine of Malaysia’s (AMM) 2016 guidelines on OHCA management, CPR must be “initiated without delay when indicated” on adult OHCA victims – who are unconscious and have abnormal or stopped breathing – placed in a supine position on the ground. Guidelines state that CPR can only be withheld in situations of “clinical irreversible death”.

The “clinical irreversible death” situations listed by AMM’s College of Emergency Physicians do not include algor mortis, but include instead rigor mortis (body stiffens after a few hours from death); dependent lividity (bluish-purple discolouration of skin after death); fatal injuries like decapitation, transection (cutting across, typically a tubular organ), or incineration (more than 95 per cent full thickness burns); or decomposition.

Dr Haris said there have been cases where the heart of a cardiac arrest patient starts pumping again beyond 20 minutes after collapse, but typically the brain is dead, which means that the patient will be held in the intensive care unit (ICU) for a week at most and subsequently still die. “Hence, public CPR is a very important gap to bridge.”

Can Paramedics Withhold CPR, Pronounce Death?

In general, the ambulance response team will try to revive patients with a chance of recovery, Dr Haris said. “Those for whom the time of arrest is less than 15 minutes will be resuscitated. Those for whom CPR was commenced early by bystanders will be resuscitated by the team.”

Dr Haris said resuscitation is withheld for those with rigor mortis, while algor mortis that had already set in with no CPR started by bystanders also indicate futility.

“If bystanders perform CPR early at the incident site, the ambulance team would take over, continue the CPR and even bring the patient to the hospital with the CPR continued for advanced care.

“Nevertheless, in the case mentioned, the time was well beyond 15 minutes. The personnel, upon arrival examined for signs of life and also attached the cardiac monitor for any signs of cardiac activity. On top of that, there was a documentation of ‘algor mortis’. All these indicate the futility of CPR,” Dr Haris said.

“In most cases, when teams respond in-house etc, the team will still do the CPR for the benefit of the doubt, regardless of the timelapse. To assume that they won’t is not depicting the true picture of what is currently happening on the ground.”

“Any patients we receive at the hospital, regardless of the time of arrest, we will still do CPR with all the equipment. We would try everything and even beyond international recommendations, as we have full equipment and manpower.”

Dr Haris (pseudonym), emergency specialist at a public hospital in the Klang Valley

When asked if it was acceptable protocol for paramedics to leave patients in the car, as was in Kumaraveloo’s case, instead of removing them from the vehicle and placing them in a supine position on a stretcher, Dr Haris again pointed to the paramedic’s clinical examination that showed no signs of life on arrival.

He said the cardiac monitor can function when the patient is in a sitting position.

“An accident scene is a police investigation scene. When a paramedic, upon his assessment, found that the body is already cold and stiff with no cardiac activity shown on the machine, the paramedic would pass the scene to the police for investigation. It was probably that – that was on the mind of the paramedic who responded,” Dr Haris said.

CodeBlue reported — based on eyewitness accounts and the HRPB MA’s Pre-Hospital and Ambulance Service (No Sign of Life) report that he signed on April 13 at 6.40pm – that the paramedic did not remove 43-year-old Kumaraveloo from his car to perform CPR or to use an available AED device from the ambulance to revive him, claiming signs of algor mortis.

The MA’s report stated that he arrived at the scene at 6.30pm, within 10 minutes from HRPB, or 20 minutes from Kumaraveloo’s approximate time of collapse at 6.10pm. It is unknown when exactly the 999 call was made, but 999 diverted the call to HRPB’s MECC at 6.17pm, which is 13 minutes prior to the ambulance’s arrival.

Dr Ammar said withholding CPR is done on a case-to-case basis as there are no designated recommendations on when CPR should be stopped or withheld.

“It depends on the person or team that is managing the patient. Some people will do everything under the sun, and some people will continue for two hours.”

Dr Ammar (pseudonym), emergency specialist at a public hospital in Selangor

“So, it depends on the health care provider and the team to decide when to stop or to not administer CPR. In this case, the team decided not to administer CPR,” said Dr Ammar, who also noted algor mortis, fixed and dilated pupils, and stiff joints as signs that CPR would be futile.

On pronouncing a patient’s death, Dr Haris said only doctors can “certify” the cause, time, and date of death.

“Nevertheless, the ambulance team not consisting of doctors could recognise signs of death and ‘pronounce’ death. The ambulance team reports back to the base and decisions are discussed with the base,” Dr Haris said.

Malaysian Protocols Follow International Standards

Dr Ammar, who is a former office bearer of AMM’s College of Emergency Physicians, said AMM’s 2016 guidelines follow international standards set by the American Heart Association (AHA), European Resuscitation Council (ERC), the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) CPR guidelines – with the latter reviewed every five years.

At the national level, Dr Ammar said the MOH’s National Committee on Resuscitation Training is responsible for providing recommended guidelines for states to adopt and adapt based on their individual capabilities.

“This committee will issue a guideline that is basic that can be followed by all parties. Usually when most of these protocols are issued, the states can add on, not deduct from it.

“That means the basic requirement set is a standard that everyone can follow. But if they want to add on to the protocols, they can if they have the capacity to do so.

“For example, if they want to add that every patient that you do CPR on, needs to be done using mechanical CPR, they can. The problem arises when you say ‘must’ but they don’t have that ability, so how are they supposed to do it?”

Beating The Odds Of Survival

Surviving an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is rare, not just in Malaysia, but globally, Dr Ammar and Dr Haris said. In the United States, more than 350,000 Americans experience cardiac arrest each year outside a hospital. Another 275,000 such cases occur in Europe.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 90 per cent people who have cardiac arrest outside the hospital die, but early CPR can double or triple the survival odds.

The MOH’s target emergency response time is 15 minutes. The current international recommendation for ambulance response time to medical emergencies is eight minutes for at least 90 per cent of ambulance calls.

A study in Sweden published in the Journal of the American Heart Association in 2020, found that shorter ambulance response time and bystander-initiated CPR resulted in reduced mortality from OHCA. However, little is known about the importance of ambulance response time in other emergencies.

In the UK, ambulance trust response is divided into four categories.

Cardiac arrest cases fall under Category One – alongside other life-threatening injuries or illnesses such as motor vehicle collisions, stabbing, or gunshot wounds – where 90 per cent of cases should get immediate response within 15 minutes.

For Category Two cases (serious conditions such as stroke or chest pain), the response time for 90 per cent of all cases is 40 minutes.

For Category Three cases (urgent problems such as an uncomplicated diabetic issue), the response time is 120 minutes or two hours, while for Category Four cases (non-urgent problems such as stable clinical cases requiring transportation to a hospital or clinic), the response time is 180 minutes or three hours.

Earlier in March, Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin had set an ambulance response time target of 15 to 30 minutes for medical emergencies within a 10 km-radius for the Ambulance Hotspot project by the Malaysian Red Crescent Society (MRCS) and St John Ambulance of Malaysia (SJAM). The number of hotspots nationwide will be increased to 20 this year.

The project was officially launched in 2021, though pilot programmes were conducted as early as 2016. Then-deputy director-general (medical) of the MOH, Dr Jeyaindran Sinnadurai, told The Star that the ultimate aim of the programme was to deliver a medical emergency response in less than 15 minutes, or possibly 10 minutes, in line with international standards.

He was quoted as saying that complaints made by the public point to ambulances arriving late, with some taking up to 45 minutes to reach the scene of an emergency.

Under the pilot programme, ambulances were placed at “hotspots”, described as areas where a high number of Malaysia Emergency Response Services (MERS 999) calls are likely to be made.

A study published in 2020 in the Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine on ambulance response time in Universiti Sains Malaysia Hospital (HUSM) in Kelantan, found that 84.7 per cent of 300 ambulance calls studied from January 2016 to January 2017 had delayed response time. The average ambulance response time at HUSM was 14.1 minutes.

Local researchers attributed distance, location type, and ambulance mechanisms as factors for the delayed response time of which distance was found to have the largest effect.

Another study published in 2020 in the Borneo Journal of Medical Sciences showed that having pre-dispatched ambulances deployed at hotspots during peak hours (8am-10am and 4pm-6pm) in Sabah led to a significant reduction in average ambulance response time from 17.31 minutes to 12.23 minutes.

Despite the various strategies deployed to reduce response time, Malaysia still lags behind international standards of eight minutes. In any case, a cardiac arrest patient would have suffered severe brain damage or died, with brain death setting in after four minutes.

Many studies have shown that a higher survival rate for OHCA is more likely among patients who receive bystander CPR. A study in Denmark published in 2016 linked bystander CPR while waiting for an ambulance to a doubling of 30-day survival for OHCA patients, even in cases of long ambulance response time.

However, absolute survival associated with bystander CPR declined rapidly with time. Researchers noted that decreasing ambulance response time by even a few minutes could potentially lead to many additional lives saved every year.

Lessons From Kumaraveloo’s Case

“It’s better that we learn from this incident,” Dr Ammar said. “The public should be aware of these types of incidents and know that there are ways for them to help.”

Firstly, the public is highly encouraged to learn basic life support skills, particularly CPR and the use of AED devices.

Secondly, information is critical. “When you are calling 999, you have to be willing to help to provide information and intervention, if required. For example, you can say, ‘What should I do while you’re coming?’ and that could trigger the call receiver or the person on the line to advise you on what to do while waiting for the ambulance to come,” Dr Ammar said.

Thirdly, Dr Ammar said it is high time that the government takes interest or a bigger role in looking at creating awareness to the public on CPR and AED. “That’s the only way forward – educating the public on their role in these types of cases when it happens.”

He said the government can also do more to improve prehospital care services, which require more manpower and ambulances to cover certain areas with a reduced response time.

“We’ve been asking this for so many years. It’s hard to get that political will to show the way and to provide because it goes back to dollars and cents, which is not something that typically catches the eye or interest of the government.”