Malaysia’s Covid-19 data is nothing to shout about. The cumulative number of confirmed cases exceeded 2.5 million on November 6, 2021, and its global ranking in the cumulative number of confirmed cases rose from 89th position on November 18, 2020 to 20th position on September 27, 2021.

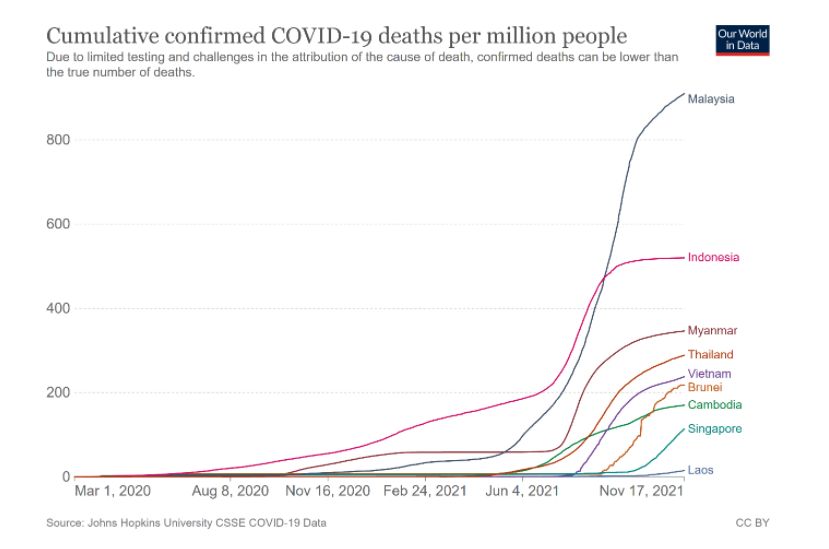

The number of deaths from Covid-19 has already passed 30,000; Malaysia’s deaths per million population is the highest in ASEAN, and the third highest in Asia. This is obvious from the graph below.

Malaysia’s confirmed Covid-19 deaths per million population is about 1.4 times that of the world. It is 1.7, 2.2, 2.6, 2.7, 3.2, 3.9, 5.4, and 9.8 times more than that of Indonesia, the Philippines, Myanmar, India, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Singapore respectively.

According to the Statistics Department, there were 44,307 and 65,584 deaths in the second and third quarters of 2021 respectively. These were 10.1% and 60.5% more than the second and third quarters of 2020 respectively.

There were fatal errors which contributed to the sad statistics above.

It was not just a single error, but a series of errors, some of which occurred concurrently that contributed significantly to the cases and deaths. Some of the major errors are discussed below.

Testing

In the absence of any definitive treatment, the basic public health procedure in managing Covid-19 was, and still is, Find-Test-Trace-Isolate-Surveillance (“FTTIS”).

A statement by the director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 16, 2020 that read “You cannot fight a fire blindfolded. And we cannot stop this pandemic if we don’t know who is infected” is as relevant today as it was then.

This was reiterated in the WHO’s recommendations for national testing strategies, dated June 25, 2021, i.e. “Diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2 is a critical component to the overall prevention and control strategy for Covid-19. It is critical that all SARS-CoV-2 testing is linked to public health actions to ensure appropriate clinical care and support and to carry out contact tracing to break chains of transmission.”

Insufficient testing and by extension, contact tracing were one of the primary contributing factors to the large number of cases and deaths in Malaysia.

On January 21, 2021, the Ministry of Health (MOH) stated that there were 68 facilities then that were conducting reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests.

Their capacity of 70,000 then could be ramped up to a maximum of 100,000 daily. At the start of the pandemic, there were 23 facilities that could conduct about 1,000 RT-PCR tests daily.

The MOH stated it was then looking into the establishment of new testing facilities in Tawau and Lahad Datu, which the then-Sabah chief minister requested in April 2020.

Although the MOH had targeted to increase its testing capacity to 150,000 tests daily, no target date was mentioned.

RTK-Ag tests which gives a result within 30 minutes was first made available to the public in Selangor in November 2020.

According to MOH data, 57,329 RT-PCR and 38,118 RTK-Ag tests were done on January 21, 2021. The tests carried out first exceeded 150,000 tests on July 28, 2021, when 151,298 tests (73,500 PCR and 77,798 RTK-Ag) were done, six months after the MOH announcement of this target on January 21, 2021.

The WHO’s benchmark for the adequacy of testing was a positivity rate of 5 per cent or less.

According to MOH data, there was undertesting for 10 weeks since November 6, 2020, with positivity rates exceeding 5 per cent. The MOH circular dated January 13, 2021, which directed that testing be done only on the symptomatic was met with questions from health care professionals about its rationale.

Later, a replacement circular issued on February 17 directed that all close contacts of a positive case be tested.

The positivity rate then went below 5 per cent. However, the positivity rate exceeded 5 per cent again from mid-May for 22 weeks, was in double digits from mid-July, reached a weekly high of 14.3 per cent from September 12 to 18, and then declined to 4.88 per cent from October 17 to 23.

The MOH’s claim, at one time, of the adequacy of a positivity rate of less than 10 per cent was a pathetic excuse, especially when it has always adhered to WHO guidelines.

Reports of delays in getting the results of tests raised many eyebrows. The admission that there was a backlog of more than a week in getting test results in Sabah was very disturbing, especially when this problem had yet to be addressed more than 18 months after the pandemic began despite exhortations from various quarters.

The delays impeded the effectiveness of testing and contact tracing, allowing the virus time and space to continue its spread in the community.

It took the MOH more than 18 months to disclose that there were an estimated three cases for every detected case.

It was patently clear, from the above, that there was insufficient testing, and by extension, contact tracing, for many months.

What were the reasons for this? Was it due to insufficient testing capacity because of unavailability of test kits, insufficient personnel or both? It could not be budgetary constraints, as hundreds of millions were allocated for management of Covid-19.

The costs of test kits were miniscule compared to that of the ventilators, ambulances and other high-end equipment purchased? Were priorities misplaced? Were there other reasons?

The MOH has yet to provide plausible explanations. The inescapable impression was that it was a case of penny wise, pound foolish.

While there has been rhetoric about moving from a pandemic to endemic state, there is still, as yet, no National Testing Strategy.

Contact Tracing

The WHO’s benchmark for successful Covid-19 contact tracing was to trace and quarantine 80 per cent of close contacts within three days of confirmation of a case — a goal which few countries have achieved.

Some scientists have considered the WHO benchmark insufficient. They said that modelling suggested that even if all cases isolated and all contacts were found and quarantined within three days, the epidemic will continue to grow.

They also said that 70 per cent of cases need to isolate, and 70 per cent of contacts need to be traced and quarantined in a day to slow viral spread.

What is known, however, is that contact tracing has been done manually by the MOH. When the numbers of positive cases surged, public health care workers could not cope.

This has, and will continue to, impact significantly the numbers that can be traced with a consequential impact on community spread.

The Expert Advisory Group (EAG), in its meeting with the then health minister on March 26, 2021, had advised for automated notification and declaration of close contacts via MySejahtera, with a cut-off point of 24 hours.

The EAG noted, in its September 13, 2021 report, that there were inadequate human resources at district health offices for contact tracing investigations.

The MoOH has provided little information about its contact tracing activities, in particular, its compliance with the WHO’s recommended benchmark or the EAG’s advice.

The need to ramp up testing and contact tracing has been addressed in a previous article.

Health Care Professionals

Health care professionals (HCPs) have been, and continue to be, society’s last line of defence against Covid-19. When a single HCP is infected by the virus, the burden for other HCPs increases markedly.

HCPs have sacrificed much, both physically and mentally, with many still reeling from the effects of their caring for infected patients.

Many HCPs have been infected. The Dewan Rakyat select committee on health, science and innovation was informed by the MOH on September 14, 2021, that 23,411 HCPs have been reported infected since March 2020, with 2,258 cases in 2020, and 21,153 until September 2021.

On October 14, 2021, the Senate was informed that 19,989 HCPs were infected, with 17 deaths reported.

Yet, the services of doctors go unappreciated. This was obvious from the extension of the contracts of contract doctors by only six months in April 2020.

The MOH’s response to reports of doctors who resigned owing to work pressure from caring for Covid-19 patients was dismissive, to say the least.

HCPs were forbidden from communicating with the media with non-compliance subject to disciplinary action. Yet, this did not stop doctors from publicising in the media the difficulties and deficiencies they encountered in treating Covid-19 patients. That doctors had to highlight such shortfalls was an indictment of the top management.

When the #hartaldoktorkontract hashtag came into the public domain, threats of deregistration were the initial response, although trade disputes are not grounds for deregistration by the Malaysian Medical Council.

Although there has been attempts to resolve the contract doctor issue since then, the whole episode has not only left a bad taste in the mouth, but must have surely impacted doctors’ morale and contributed to burnout.

It is a universally accepted that there is an association between doctors’ burnout, sub-optimal care, and patient safety.

Interface With Private Sector, University Hospitals And NGOs

The private sector and university hospitals offered their services to the MOH in April 2020 when the government stated that it was taking a whole-of-society approach towards battling Covid-19. Notwithstanding the rhetoric, the MOH gave the impression that it would be managing the situation itself, without the need for any assistance from the private sector and university hospitals.

Although university hospitals services were taken up from about the middle of 2020 onwards, their roles were secondary to that of the MOH.

On January 7, 2021, 46 senior medical professionals wrote an open letter to the then-prime minister stating their apprehension and concern about the Covid-19 situation, as the national metrics then reflected a very bleak picture of the pandemic management.

Private hospital services were only taken up in January 2021, when there was a surge of cases and MOH facilities were overwhelmed. Staff from the private hospitals had a steep learning curve, as they had not managed any Covid-19 cases until then.

In response to the open letter to the prime minister, the government formed the EAG on February 8 to provide professional input on strategy setting and operations. The last report of the EAG on September 13 noted that there were many gaps between their recommendations and what eventually transpired.

The private GPs who offered their services for Covid-19 vaccinations in early 2021 had to comply with conditions prescribed by the MOH that were not user-friendly.

Many GPs had to address the question of whether their services were really welcomed. Despite recent modifications of some of thee conditions, there are about 2,000 GP clinics providing vaccinations, out of about 7,000 clinics nationwide.

Interactions with NGOs were not coordinated. In this respect, some MOH state directors were more proactive, while there were others who did not reach out to the NGOs.

Dr Milton Lum is a Past President of the Federation of Private Medical Associations, Malaysia and the Malaysian Medical Association. This article is not intended to replace, dictate or define evaluation by a qualified doctor. The views expressed do not represent that of any organisation the writer is associated with.