The data on the Covid-19 situation in Malaysia is an indictment of its management.

The number of positive cases exceeded 1.5 million on 20 August 2021. It took 482, 65 and 27 days to exceed 500,000, 1 million and 1.5 million cases respectively.

At its current trajectory, it will exceed 2.0 million cases shortly. In the global league of cumulative reported cases, Malaysia was in the 23rd position on August 28, 2021, up from 39th on May 31 and 85th on November 18, 2020.

The number of total reported deaths exceeded 15,000 on August 26. It took 519, 39 and 21 days to exceed 5,000, 10,000 and 15,000 deaths respectively.

On August 20, the number of daily cases and daily reported deaths per million population exceeded that of India, Indonesia, and Philippines the only Asian countries with more cases than Malaysia.

It took more than 18 months for the Ministry of Health (MOH) to disclose that the estimated actual prevalence of Covid-19 is three times that of every reported positive case.

The disclosure revealed a fundamental flaw in the management of Covid-19 in Malaysia i.e. insufficient testing and by extension, insufficient contact tracing and isolation of positive cases. Undetected infected individuals would continue to spread the infection in the community.

Insufficient testing, and by extension, inadequate contact tracing, are one of the primary contributing factors to the continuing large number of cases and deaths.

In the absence of any definitive treatment, the basic public health procedure in managing Covid-19 is still Find-Test-Trace-Isolate-Surveillance (FTTIS).

The statement of the director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 16, 2020, “You cannot fight a fire blindfolded. And we cannot stop this pandemic if we don’t know who is infected”, is as relevant today as it was then — more so, with the current Covid-19 situation in Malaysia.

Testing And Public Health

Testing is part of a comprehensive strategy to suppress viral spread and save lives. It should be strategic, make the best use of available resources and link to clear public health goals.

Testing can identify symptomatic and asymptomatic cases, inform clinical management, and support contact tracing.

As individuals can become infectious within days of viral exposure and before symptoms develop, there is only a narrow window within which to identify them before they infect others.

As such, rapid testing is vital for effective contact tracing, with contacted individuals advised to isolate themselves pre-emptively while awaiting test results.

Some salient statements in the WHO’s recommendations for national testing strategies, dated June 25, 2021, include:

- Diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2 is a critical component to the overall prevention and control strategy for Covid-19.

- Countries should have a national testing strategy in place with clear objectives that can be adapted according to changes in the epidemiological situation, available resources and tools, and country specific context.

- It is critical that all SARS-CoV-2 testing is linked to public health actions to ensure appropriate clinical care and support and to carry out contact tracing to break chains of transmission.

- All individuals meeting the suspected case definition for Covid-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2, regardless of vaccination status or disease history.

- Individuals meeting the suspected case definition for Covid-19 should be prioritised for testing.

- If resources are constrained and it is not possible to test all individuals meeting the case definition, the following cases should be prioritized for testing: individuals who are at risk of developing severe disease; health workers; inpatients in health facilities; the first symptomatic individual or subset of symptomatic individuals in a closed setting (e.g. long-term care facilities) in the setting of a suspected outbreak.

- Considerations for the use of self-testing should include improved access to testing and potential risks that may affect outbreak control.

Delays in getting results impedes the effectiveness of testing.

The admission that there is a backlog of more than a week in getting test results in Sabah is very disturbing. That this problem has yet to be addressed more than 18 months after the pandemic began, is very disturbing.

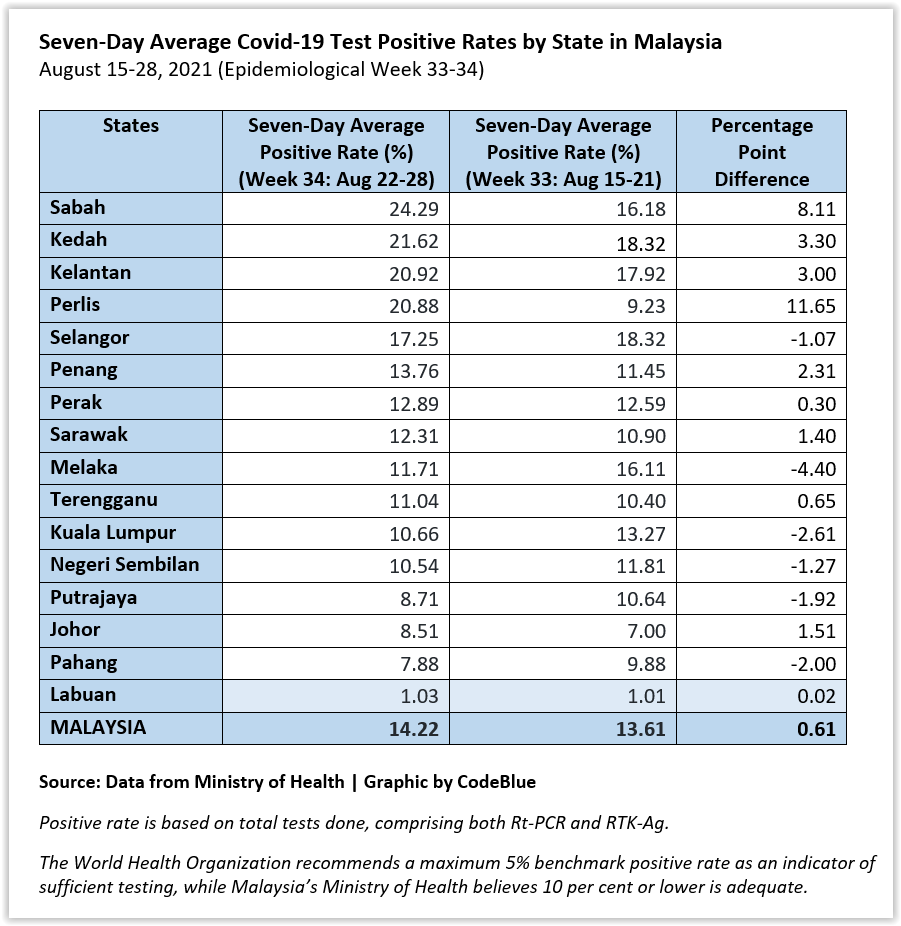

That there is inadequate testing is obvious from the table below, with wide variations in the positivity rates by states and territories.

According to the WHO, testing is considered adequate if the positivity rate is 5 per cent or less.

MOH data indicate that the positivity rate has exceeded 5 per cent since mid-May, and in double digits since mid-July. What were the reasons for this deterioration? The MOH has yet to provide an explanation.

The claim that a positivity rate of less than 10 per cent is adequate is a pathetic excuse, especially when the MOH has adhered markedly to WHO guidelines.

There are several means to scale up testing. They include use of rapid antigen tests, pooling of samples, point of care testing, self-testing and utilisation of private sector facilities by the MOH.

While self-test kits have been approved for sale in pharmacies and health care facilities, the MOH has yet to come out with public information about the potential benefits and harms of self-testing.

Covid-19 self-tests cannot be treated like pregnancy self-tests.

The rakyat has a right to know what is Malaysia’s national strategy for testing and the role of self-testing. The MOH’s silence is deafening.

Contact Tracing

The usual version of contact tracing starts when someone who tests positive for Covid-19 is identified and advised to isolate (quarantine). A contact tracer interviews this person to find out who may have been exposed to them while infected, usually 48 hours before the positive test or before symptoms appear, if any.

Close contacts, i.e. those who have spent more than 15 minutes close to the infected person are of interest. This would include household members and anyone who shared meal or office space, schools, health care facilities, prisons, public transport, etc.

Tracers then call or visit these contacts to inform them about testing and quarantine so that they do not spread the virus to more people. This helps in breaking the chain of transmission.

Manual contact tracing is laborious and time-consuming, and becomes increasingly difficult with widespread community spread. The increase in diagnosed cases leads to large numbers of secondary contacts who must in turn be identified, tested and isolated. The increasing case burden results in delays which may decrease the effectiveness of contact tracing further.

Once the disease burden exceeds contact tracing capacity, most secondary cases are contacted too late, and tracing will have little further effect on viral spread.

The WHO’s benchmark for successful Covid-19 contact tracing is to trace and quarantine 80 per cent of close contacts within three days of confirmation of a case – a goal which few countries have achieved.

The WHO benchmark has been considered insufficient by some scientists who state that modelling suggests that even if all cases isolate and all contacts are found and quarantined within three days, the epidemic will continue to grow.

They state that 70 per cent of cases need to isolate and 70 per cent of contacts need to be traced and quarantined in a day to slow viral spread.

Some salient statements in the WHO’s recommendations for Covid-19 tracing dated February 1, 2021 include:

- Contact tracing – along with robust testing, isolation and care of cases – is a key strategy for interrupting chains of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and reducing Covid-19-associated mortality.

- Contact tracing is used to identify and provide supported quarantine to individuals who have been in contact with people who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 and can be used to find a source of infection by identifying settings or events where infection may have occurred, allowing for targeted public health and social measures.

- In scenarios where it may not be feasible to identify, monitor and quarantine all contacts, prioritization for follow-up should be given to contacts at a higher risk of infection based on their degree of exposure; and contacts at a higher risk of developing severe Covid-19.

- Digital tools can enhance contact tracing for Covid-19, but ethical issues around accessibility, privacy, security and accountability need to be considered as they are designed and implemented.

- Ideally, contact tracers should be recruited from their own community and have an appropriate level of general literacy, strong communication skills, local language proficiency and an understanding of the local context and culture. Contact tracers should be informed on how to keep themselves safe.

- Close and consistent engagement with communities is critical for successful contact tracing.

The MOH has provided little information about its contact tracing activities, in particular, its attainment of WHO’s recommended benchmark or otherwise.

It would not be unreasonable to infer from the paucity of information that there are marked deficiencies in contact tracing.

Failures

The reality is that failures occur at every stage of the test-trace-isolate sequence. People get infected and do not know it or there is a delay in getting tested.

Results can take days to be positively confirmed. Not everyone isolates while waiting for results, nor does everyone who tests positive isolate.

Not everyone can provide details of their close contacts. Not all contacts are reached or isolate while waiting for results.

The reasons for failures are complex and systemic. Malaysia’s contact tracing uses antiquated technology and is underfunded.

Overstretched public health staff have to overcome public distrust and scepticism about the government’s efforts to rein in Covid-19 which is also fuelled by policy flip-flops.

The dearth of data stymies analysis for decision-making.

Yet there are countries which have successful contact tracing including China and South Korea. A measure that worked included tracing multiple layers of contacts.

A study in Hong Kong found that 19 per cent of cases of Covid-19 were responsible for 80 per cent of transmission, and 69 per cent of cases didn’t transmit the virus to anyone. Any new case is more likely to have emerged from a cluster of infections than from one individual, so there was value in going backwards to find out who else was linked to that cluster.

Japan recognised this early and adopted cluster-focused contact-tracing; it traces contacts up to 14 days before symptom onset, rather than the usual 48 hours.

Digital technology has been shown to be helpful e.g. software that streamlines conventional contact tracing, use of data surveillance techniques, use of mobile phone location data, and smart phone applications that inform users that they might have been exposed to the virus.

These technologies can automate contact tracing and ease the burden of public health staff but it requires widespread adoption and adherence.

Contact tracing applications have met with privacy concerns which the authorities have to address by providing sufficient reassurance to the public.

Ramp Up Testing And Contact Tracing

It is myopic for anyone to think that vaccination is the silver bullet for the widespread community spread of Covid-19 in Malaysia. The message from WHO is unambiguous.

Although vaccination is an important intervention, other interventions are required.

As there is no definitive treatment, the basic public health procedure in managing Covid-19 is still FTTIS.

It is time that the government get back to basics and ramp up testing and contact tracing. The target should be to attain and maintain the WHO benchmark of 5 per cent positivity rate, as well as to trace and quarantine 80 per cent of close contacts within three days of confirmation of a case.

The public disclosure of such data will go a long way in improving public trust.

Dr Milton Lum is a Past President of the Federation of Private Medical Associations, Malaysia and the Malaysian Medical Association. This article is not intended to replace, dictate or define evaluation by a qualified doctor. The views expressed do not represent that of any organisation the writer is associated with.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.