KUALA LUMPUR, March 9 — An inquiry into the deadly 2016 blaze at Johor’s Sultanah Aminah Hospital (HSA), the worst hospital fire in Malaysia, found that the government facility operated for years without a fire certificate.

The independent investigation by a seven-member committee led by former Court of Appeal judge Mohd Hishamudin Yunus uncovered, among various disturbing issues, that despite previous fires in the Ministry of Health (MOH) hospital since 2008, the entire HSA management and the ministry did not appear to take fire safety seriously.

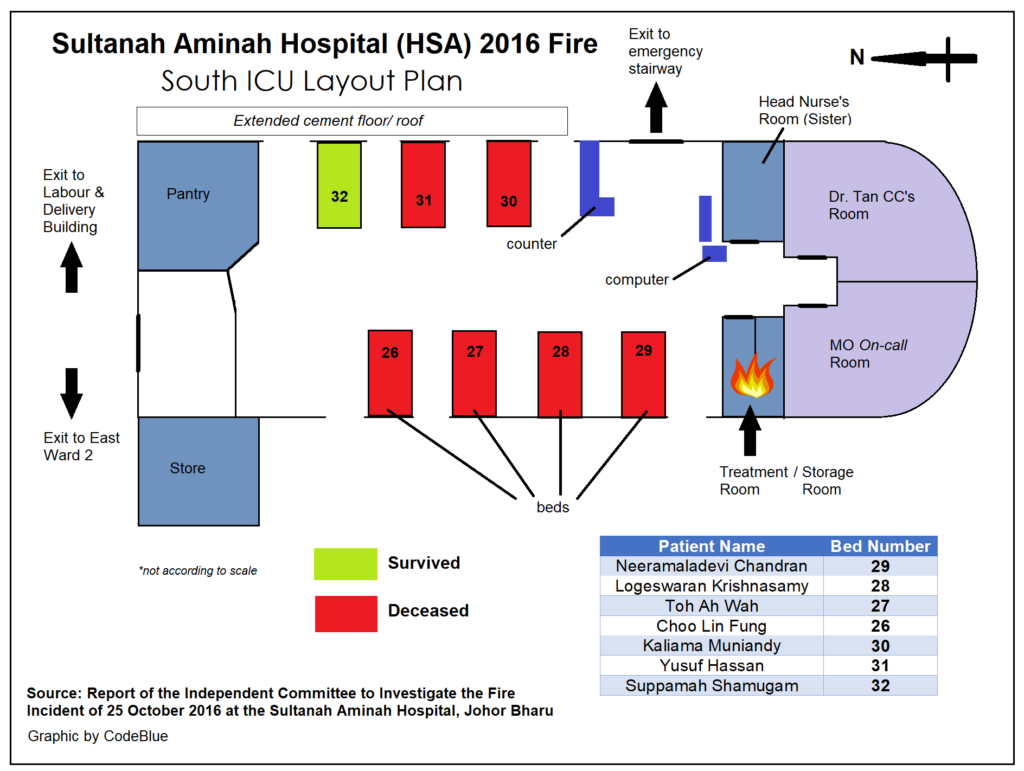

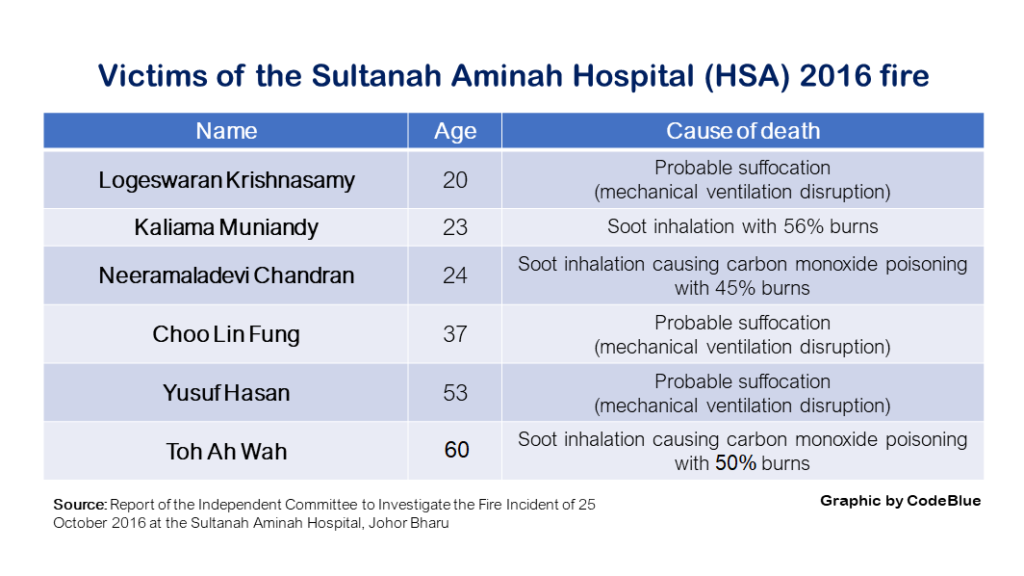

Six patients, most of whom were in their 20s and 30s, died when a fire broke out on October 25, 2016 at the South Intensive Care Unit (ICU) ward in the hospital in Johor Baru, while one patient was seriously injured. HSA is one of the busiest hospitals in Malaysia based on patient load. The main building was constructed between 1938 and 1941, while HSA’s ICU, the first public one in Malaysia, officially opened in 1969.

The Fire and Rescue Department (Bomba), despite being aware that HSA did not have a fire certificate that it had been trying unsuccessfully to obtain since 2002, did not seriously enforce the law on the government hospital either, according to the independent inquiry’s 225-page report, as sighted by CodeBlue.

“It is our finding that one of the underlying causes that led to the deaths of patients and injuries to a patient and several staff of the South ICU was the lack of preparedness on the part of the hospital management and staff.”

Report of the Independent Committee to Investigate the Fire Incident of 25 October 2016 at the Sultanah Aminah Hospital, Johor Bharu

The inquiry found that none of the South ICU staff had undergone training in fire drills or emergency evacuation, despite four previous fire outbreaks in the ward in 2008, 2010, and May and October 14, 2016 before the October 25 blaze.

HSA’s guidelines on fire safety and disaster management, namely the Pelan Tindakan Bencana Dalaman (PTBD), “were never taken seriously or implemented by both the management and staff”.

The public hospital’s Fire Safety Committee was dormant, there was a lack of “pre-incident planning”, there was no “fire plan” to guide the first fire crew on arrival, there was no fire safety officer at the South ICU, there was no emergency response team, and there was no water sprinkler or smoke detector system at the South ICU. A water sprinkler system, according to the inquiry, could probably have averted the fire disaster.

Only two fire extinguishers were available at the South ICU at the time of the October 25, 2016 blaze — a CO2 fire extinguisher that was found to be ineffective for that type of fire and a powder fire extinguisher that malfunctioned at the critical moment. The fire disaster, said the investigating committee, could have also been averted by the use of a suitable fire extinguisher at the time.

“Considering the number of staff present in relation to the number of patients in the ward (seven in number), and based on the evidence, we are of the opinion that the patients, or at least some of the patients, especially the patients nearer the exit doors, could have been saved had the staff been given some serious training on evacuation of patients in time of emergency.”

Report of the Independent Committee to Investigate the Fire Incident of 25 October 2016 at the Sultanah Aminah Hospital, Johor Bharu

“Instead, being untrained and unprepared for such an eventuality, the staff appeared not to be too concerned initially of the impending danger when the fire first appeared, but, subsequently, panicked when the smoke started to engulf the ward to such an extent that they were unable to even release the brakes of the beds and to push the same out of the wards,” said the inquiry.

Despite a small electrical fire that broke out at the South ICU on October 14, 2016, 11 days before the deadly blaze on October 25, and two previous electrical fires at HSA in early January 2010 (also at the South ICU) and on April 17, 2010 [at an AHU (air handling unit) room], the independent investigation found that the hospital management did not follow up on fire safety awareness.

“Instead, both the management and staff became complacent to the dangers of electrical fire.”

The fatal fire broke out in the storage room (described by HSA as the “treatment room”) of the South ICU at about 8.50am on October 25, 2016, with the Fire and Rescue Department receiving a call from the hospital at about 8.56am. But the inquiry found that Bomba, when alerted, wrongly believed that it was only a “mere electrical fire” and not the case of the hospital being on fire.

So, only one fire engine with a seven-member crew arrived at the scene at 9.05am, nine minutes after the call for assistance. The second fire engine arrived 26 minutes later at 9.22am, and the third 44 minutes later at 9.40am. The turntable ladder only arrived 50 minutes later at 9.46am.

However, according to the Fire and Rescue Department’s protocol, a fire like the one at HSA should have had three fire engines, equipped with a turntable ladder, arriving simultaneously at the scene within 10 minutes of the call for assistance, the inquiry heard.

During the fire, there was only one clear escape route from the South ICU, through the main door. The emergency exit door just outside the ward, accessible via a side emergency exit door of the South ICU, was locked, apparently for “security” reasons, with the key kept in a key box. But witnesses gave the inquiry conflicting evidence about where the key box was located.

The route from the South ICU to the outside emergency exit door was also obstructed by a counter. A steel cabinet in the lobby area outside the side emergency exit door of the ward posed another obstruction.

The inquiry also found that emergency lights and exit door sign lights were not working at the time of the incident, resulting in total darkness in the South ICU ward when the lights went off.

“This total darkness and the engulfing smoke made evacuation efforts extremely difficult.”

Old Electrical Wirings

According to the investigation, the electrical wiring at the main building of HSA was at least 15 years old. After a fire due to electrical overloading, HSA made a funding application in 2010 for electrical rewiring, but it was not approved, supposedly because “rewiring was not a priority”, according to witness testimony.

The South ICU was also infested with rats, leading to the strong possibility that the old electrical cables had been attacked and torn by rodents over the years.

The investigating committee believed that the immediate cause of the October 25, 2016 fire was due to electrical arcing, coupled with the presence of leaked medical gases rich in oxygen in the ceiling space of the storage room, where the fire was first spotted. The inquiry said the high usage of oxygen could be due to gas leakages in the gas piping system. The medical gas supplied to the bed head panel was distributed through the full height wall panel from the ceiling space. So if there had been a gas leakage within the wall panel or the ceiling space, the gas would be trapped inside the ceiling space.

Torn cables, said the inquiry, are very susceptible to arcing. Arcing is a luminous discharge of electricity across air gaps. This process could have occurred silently and invisibly. The fire, according to the inquiry, likely spread rapidly within the ceiling, causing the ceiling to collapse and to release hot and thick black smoke that engulfed the entire South ICU within seconds.

“The tragic incident of 25 October, 2016 could have been avoided if the government had manifested grave concern over the conditions of the electrical cabling/wiring in the hospital and treat rewiring of the hospital with utmost importance,” said the inquiry.

Weak Management At Hospital Level On Fire Safety

“The whole management of HSA, from the director downwards to the operating levels in the wards, failed to take fire safety seriously despite the incidence of fires in the main building of HSA since 2008,” said the investigation.

It noted that HSA did not appear to have a risk management system, pointing out that basic fire safety training activities like fire drills and evacuation drills were not done effectively.

Dr Rooshaini Merican, the Johor state health director at the time of the October 2016 fire and HSA director from 2011 to September 2016, admitted to the inquiry that the Pelan Tindakan Kebakaran (incorporated into the Pelan Tindakan Bencana Dalaman, PTBD) was not given serious emphasis as the hospital “has a lot of other plans which must be given serious emphasis.”

“This appears to be the prevailing attitude at HSA,” said the investigation.

HSA deputy director (management) Sarina Atipah — who held the position since February 2016 and was also the PTBD deputy chairwoman at the time of the October 2016 fire — told the inquiry that she had never seen the Pelan Tindakan Kebakaran and considered the committees for the PTBD and for the Pelan Tindakan Kebakaran as being “one and the same”.

She also reportedly found that many members of the various overlapping HSA committees on disaster management and fire safety had no longer worked in HSA. It was only after the October 25, 2016 fire that new committee members were appointed and sent for training with the Fire and Rescue Department. HSA also installed smoke detectors in the main building and reviewed the provision for fire extinguishers and emergency exits after the deadly fire.

“The committees dealing with fire safety and disaster management at the HSA did not function effectively at all.”

Report of the Independent Committee to Investigate the Fire Incident of 25 October 2016 at the Sultanah Aminah Hospital, Johor Bharu

The inquiry noted that fire safety officers at HSA units or wards were not appointed, while ICU staff did not go through fire drills or received training on evacuation procedures during emergencies.

When the Malaysian Society for Quality in Health (MSQH) only agreed to partial accreditation for HSA for one year and identified areas of concern, including fire safety issues and the lack of a fire certificate, HSA did seek additional funds to address these concerns. But when MOH’s Engineering Services Division rejected the hospital’s funding application for electrical rewiring, HSA did not seriously pursue MSQH accreditation, the inquiry found.

Instead, HSA sought ISO accreditation that did not address fire safety. This decision to apply for ISO, said the inquiry, could only be made by the HSA director with the agreement of MOH’s senior management.

Weak Governance At Ministry Level On Fire Safety

“It would appear that the ministry did not take matters pertaining to fire safety seriously. There was no seriousness in requiring government hospitals to obtain fire certificates or to have old wiring replaced or to seriously implement fire safety guidelines,” said the investigation.

The committee noted that priority projects requiring less funds were more likely to be funded by MOH, rather than more critical but expensive projects, like replacing old wiring.

MOH, said the inquiry, rejected HSA’s request in 2010 for a special allocation for electrical rewiring, despite previous fire outbreaks in the South ICU since 2008. MOH also denied funding for sprinkler and smoke detection systems in the South ICU. The ministry further rejected HSA’s purported applications for an electrical engineer.

Then-MOH’s Engineering Services Division director Hj Jalal allegedly told the inquiry that his division rejected HSA’s funding request for electrical rewiring because funds for hospitals were limited, and only “critical” projects were supported.

“He also said that funds were allocated according to the priority that was identified by each state, and the electrical rewiring of HSA was apparently not on the high-priority list from the Johor state health department,” said the inquiry, noting that electrical rewiring was only listed high on Johor’s priority list after the fatal 2016 fire.

The investigation blamed not only the HSA management for failing to implement fire safety guidelines and legal requirements, but also MOH for not ensuring their implementation or providing the resources needed.

“Whilst the PTBD (Pelan Tindakan Bencana Dalaman) guidelines were issued, the ministry failed to ensure that they were implemented, a major failing that contributed to the fire disaster that occurred at the HSA on 25 October, 2016.”

Report of the Independent Committee to Investigate the Fire Incident of 25 October 2016 at the Sultanah Aminah Hospital, Johor Bharu

Dr Nor Aishah Abu Bakar, head of MOH’s patient safety unit, reportedly told the inquiry that HSA scored only 53.85 per cent in its annual safety audit in 2016, the lowest among hospitals in Johor. Putrajaya Hospital achieved 100 per cent, while Seremban Hospital achieved 0 per cent. HSA’s performance, according to her, was below MOH’s 70 per cent target and was considered unsatisfactory.

Although MOH supported the global movement on patient safety by launching Malaysia’s Patient Safety Council in 2004, “the management of quality and safety at HSA level was weak, lacked leadership, and was inclined to focus only on routine administrative issues. Ministry’s guidelines were not implemented effectively.”

Illegal Act And Broken By-Laws

According to the independent investigation, the circuit protective conductors (CPCs) for the ICU electrical system had been disconnected from the earth terminal, posing a “serious danger” of electrical fire in the event of an overcurrent.

“Disconnecting CPCs from the earth terminal is certainly a bad practice and an illegal act,” said the inquiry, citing Section 33C of the Electricity Supply Act 1990 and Regulation 34 of the Electricity Regulations 1994. “Such an act had made the building totally unsafe.”

The design specification of the storage room where the fire was first spotted, said the inquiry, broke by-law 139 of the Uniform Building By-laws 1984 or the Uniform Building By-laws 1986 of Johor (UBBL). HSA staff, however, had referred to it as a “treatment room”, which the committee believed may have been the original purpose of the room.

The storage room, according to the inquiry, stored several combustible items in substantial quantities that could be considered hazardous. Among the items kept in the storage room were Toyogo-brand plastic containers, built-in cabinets, swabs, syringe sets, plastic materials, disposable dressing sets, bandages, gamgee tissues, and a refrigerator containing ice packs and medicines.

According to the UBBL, such high-risk areas are required to be designed as separate fire risk areas with full compartmentation of the floors, ceilings, and walls, and including fire-resistant doors. The walls must be fire-rated and must be constructed up to the soffit of the upper floor slab. The doors must have door closers, hinges and door handles approved by the Fire and Rescue Department.

Non-compliance with by-law 139 requirements in the design specification of the storage room “had caused the fire to spread quickly such that the staff did not have sufficient time to evacuate the patients and themselves from the South ICU.”

The investigation found that the “inappropriate building materials” used in the construction of the South ICU had also contributed to the severity of the fire.

Under by-law 136 read with the 8th Schedule of the UBBL, the South ICU must be constructed with the size of compartmentation of not bigger than 2,000 square metres. The compartmentation must be constructed with a minimum of one-hour fire resistance partition elements and a fire resistance door.

“It is our finding that the South ICU was previously renovated and was installed with non-fire rated doors that compromised the fire resistance performance of its compartmentation,” said the inquiry.

The main entrance door to the ICU, the inquiry found, had been replaced with an automatic sliding glass door that did not comply with the fire resistance compartmentation requirement of the UBBL. The secondary emergency exit door was also built without complying with the fire resistance door requirement.

“The installation of these doors compromised the fire compartmentation of the South ICU, thus allowing fire to easily spread to other areas.”

The gypsum partition wall used for the construction of the South ICU was not of the fire resistance type either, as it ended just above the ceiling level, but did not extend to the soffit of the upper floor slab. Thus, the ceiling space of the storage room and the ceiling space of the South ICU patients’ bed area were connected above the ceiling level, violating by-law 139 for the separation of fire risk areas.

“The committee finds that the fire started from the ceiling space above the storage room and spread very quickly to the ceiling space above the patients’ bed area,” said the inquiry.

“If the storage room had been constructed in accordance with the UBBL (Uniform Building By-laws), the risk of the fire spreading could have been reduced, and the fire probably might have been contained within that risk area inside the storage room.”

Report of the Independent Committee to Investigate the Fire Incident of 25 October 2016 at the Sultanah Aminah Hospital, Johor Bharu

The Area Valve Service Unit (ASVU) serving the South ICU ward, according to the independent investigation, was located inside the ward — that was then on fire and was not accessible — which means that the AVSU for the South ICU medical gas supply was not turned off when the fire occurred. The medical gas supply system was only shut down after the fire was brought under control at about 3pm that day.

One of the two ASVUs in the South ICU and a gas terminal unit were located inside the pantry of the ward, which the inquiry described as an “unacceptable and unsafe practice.”

“Medical gas main shut-off valves must be easily accessible and should not be located at a high-risk area such as kitchen, pantry, or linen storage area.”

HSA And Government’s Defence

The six patients who died in the October 2016 fire at HSA were Logeswaran Krishnasamy, 20; Choo Lin Fung, 37; Toh Ah Wah, 60; Yusuf Hasan, 53; Kaliama Muniandy, 23; and Neeramaladevi Chandran, 24.

Neeramaladevi’s parents have filed a negligence lawsuit against the HSA director, the Johor state health director, and the government over their daughter’s death in the fire.

The HSA director and the government have since denied negligence. All three defendants also claimed in their defence that HSA staff prioritised patient safety, were “frequently trained” for emergencies, and were “trained and experienced”. They also claimed that maintenance and repairs on electrical wiring and facilities at HSA followed standards and procedures. They further alleged that HSA prepared an efficient evacuation plan and that all rescue efforts were conducted quickly and efficiently.

Then-Health Minister Dr S. Subramaniam in the Barisan Nasional government reportedly told Parliament on October 26, 2016 that MOH and Medivest Sdn Bhd, a hospital support services company serving HSA, did prepare a fire prevention standard operating procedure and a contingency and emergency response plan.

The seven-member independent investigating committee, which was appointed by Dr Subramaniam, comprised chairman Hishamudin, deputy chairman Dr Abu Bakar Suleiman (former Health director-general), and members Adanan Mohamed Hussain (former Public Works Department director-general), Soh Chai Hock (former Fire and Rescue Services Department director-general), Shahronizam Noordin (manager of Occupational Health Safety Division, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health), Ezumi Harzani Ismail (member of the Board of Architects, Malaysia), and Mohd Zailan Sulieman (senior lecturer, School of Housing, Building and Planning, University of Science Malaysia).

The committee conducted its inquiry in 2017, after hearing evidence from 40 witnesses and receiving 217 exhibits. The witnesses included medical officers, nurses, a pharmacist, and a cleaner at the scene of the October 2016 fire at the South ICU; firefighters from the Fire and Rescue Department who put out the fire; technical experts from the Fire and Rescue Department, the Public Works Department, and the Energy Commission that probed the fire; and the-then Johor state health director, who was the former HSA director.

The investigating committee handed its report to MOH in June 2018 under the Pakatan Harapan (PH) administration. On October 2, 2019, the Cabinet decided that MOH was to publish the report. Then-Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad did not do so.

However, Dzulkefly confirmed with CodeBlue on February 24 this year that the HSA report has been declassified as a state secret.

After a political tussle, PH lost federal power last March 1 when Muhyiddin Yassin — leading a new coalition called Perikatan Nasional comprising Bersatu, Umno, MCA, MIC, and PAS, supported by Sarawak’s GPS — was sworn in as prime minister. The new health minister is Dr Adham Baba, while Deputy Health Minister I is Dr Noor Azmi Ghazali and Deputy Health Minister II is Aaron Ago Dagang.

Part 2: Why Bomba Didn’t Charge ‘Fire Hazard’ Sultanah Aminah Hospital

Part 3: Company Gave HSA Faulty Fire Extinguisher, Falsified Data: Inquiry Hears

Part 4: Take Legal Action Against Medivest, HSA Fire Inquiry Tells Government