KUALA LUMPUR, July 29 — Private hospitals are expensive because they spend on preventive measures for worst-case scenarios to avoid lawsuits from patients, Thomson Hospital Kota Damansara’s CEO said.

Nadiah Wan said private hospitals provided an emergency team on standby in an operating theatre all the time, in case a patient needed an emergency surgery or resuscitation.

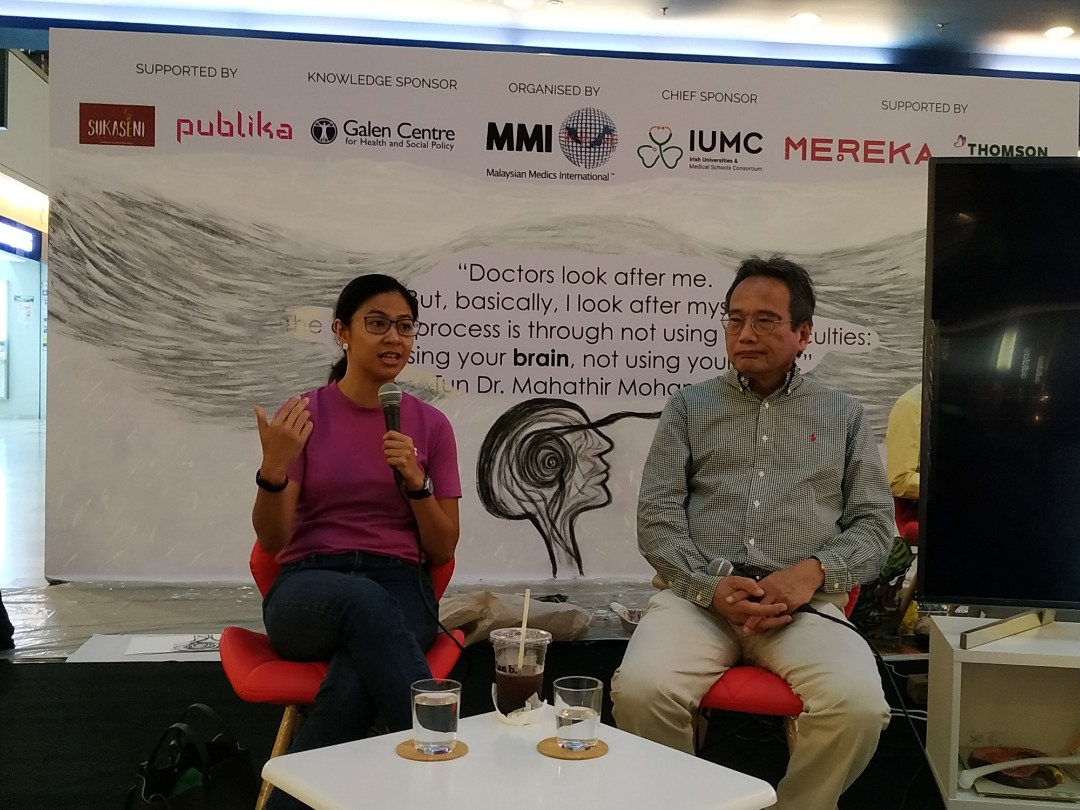

“So, ‘just in case’ actually costs a lot of money,” Nadiah told Malaysian Medics International’s (MMI) “The Good Doctor: A Health Care Festival” at Publika recently.

“At present moment, our health care technology and knowledge is very good. We can keep people alive for a very long time. They can live with cancer, they can live with diabetes for 20, 30 years, but that costs a lot of money.

“So the cheapest way to manage your health care costs is actually to not fall sick in the first place. But this is a message that a lot of people don’t like to hear, but unfortunately, it’s true,” added the CEO of the Selangor-based private hospital.

Nadiah said hospitals ran many backup systems and equipment 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for things like infection control and operating theatres.

She also highlighted the threat of litigation from patients, noting that while people in the past understood that certain medical procedures carried certain risks, “tolerance for risks” was now very low.

“So if something were to go wrong, you’ll start getting lawyer’s letters, you’ll start getting demands for compensation. So that is actually influencing hospitals and doctors to actually do more than required, to actually protect themselves just in case,” said Nadiah.

She acknowledged that while some may complain about their doctor ordering a CT scan for a simple condition like persistent stomach ache, for example, the doctor may look at it as a possible case of appendicitis that could lead to complications if it was not diagnosed in time.

“A lot of these things that are happening, especially in tertiary hospitals, people expect things to be done. And the doctors have to do certain things just to double check to make sure. And that results in a higher cost of care.”

Monash University consultant endocrinologist Dr Khalid Abdul Kadir claimed that people now demanded a battery of tests because of increased information, or misinformation, on the internet about illnesses.

He pointed to patients demanding CT scans for simple conditions like headaches.

“If I don’t do a CT scan, they’ll say I’m not good enough, they go to another doctor. But we have to justify to insurance companies why we want to have a CT scan when I could easily diagnose that all she has is a tension headache,” Dr Khalid told the MMI conference.

He also highlighted the problem of lawsuits from dissatisfied patients and pointed out that doctors, particularly surgeons and obstetricians, were forced to pay insurance premiums as high as over 1.5 or two months’ worth of income every year.

“Why is this so? Because public again is demanding the highest level of care,” said Dr Khalid, citing a High Court ruling in Malaysia about two and a half years ago that stated specialists or consultants could not make mistakes, unlike general practitioners (GPs).

“So, to protect ourselves, we have to do certain tests to make sure we don’t miss things,” he added. “If the public is aware that it is they themselves who are demanding more and more from doctors and health service, then they should realise they have to pay for it.”

When asked about medical specialists leaving the civil service for the private sector, Nadiah highlighted a Health Ministry ruling that requires hospitals to have resident, or full-time doctors, for any service that they want to provide.

She pointed out, however, that certain fields like paediatric surgery may have doctors conducting congenital surgery in multiple hospitals because such an operation may not be very common in one particular location. But the Health Ministry requires doctors to serve full-time if a hospital states that they provide such inpatient services.

“I understand why they do it – they’re very worried about continuity of care if something were to happen to the patient,” said Nadiah.

“But the flip side is that hospitals are then incentivised to make sure, pay them an income or whatever, so that they state they’re resident in that hospital. So a lot more of, sort of, trying to get these residents out and into the private sector just so we can provide that service.”

Then-Health Minister Dr S. Subramaniam reportedly said in January 2018 that the number of medical specialists quitting public hospitals was rising annually because of the much bigger salaries in the private sector, noting that 170 government specialists resigned in 2017, up from 158 in 2016.

Dr Subramaniam said then that the government tried to curb the exodus of specialists by introducing flexible working hours from January 1 last year, so that they can spend one day a week to do research, lecture at universities, or work in the private sector.

But Nadiah highlighted inflexibility and stigma against Malaysian doctors working part-time, unlike in countries like Australia that are fine with doctors practicing in both public and private institutions.

“And I think over here in the public service, there is a stigma for doctors who are seen to be working in the private sector who are there just to make money,” she observed.

“And actually, frankly, I’ll be happy to allow my doctors to work in the public sector part-time because I might not need them all the time.

“But it’s seen as if like once they leave the Ministry, that’s it, the door is closed for you. I think it’s a major waste because there are not many of these people around.”