KUALA LUMPUR, April 18 — Only slightly more than one in 10 Malaysian women do a pap smear once ever, even though the test is recommended every three years.

On the rare occasion that a woman does a pap exam at a government clinic to screen for cervical cancer, she has to wait three months for the facility to call her, only if results are abnormal. Results are presumed to be normal in the absence of a call.

So, Universiti Malaya consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Woo Yin Ling, along with Australian experts from non-profit VCS Foundation, envisioned a system called ROSE (Removing Obstacles to Cervical Screening) that aims to track all women and to remind them to take a HPV cervical screening test upon hitting 35.

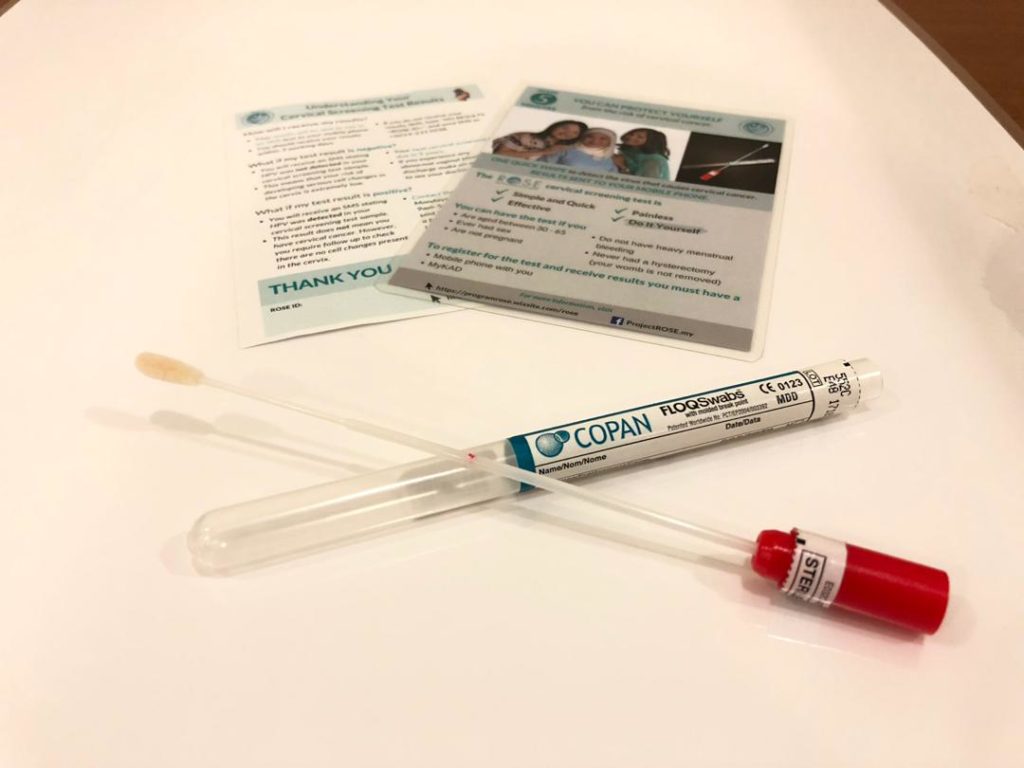

The HPV test, which is more sensitive than a pap smear, is self-administered and produces results in three days.

With a system that reminds women to get screened, provides them the test results, and ensures follow-up for abnormal results, Dr Woo hopes to get all women in Malaysia aged between 30 and 65 taking the HPV test three times in their lifetime.

“Screening is like a whole obstacle race,” Dr Woo told CodeBlue in a recent interview.

“The test is just one obstacle. We really need to move towards any screening intervention as a course of obstacles, at which every obstacle you need to deal with, from getting the women to go to the obstacle in the first place. If we are very good at doing the test, but we’re not good at doing follow-up, which is the next obstacle, we don’t finish the race at all,” she added.

The ambitious ROSE system aims to make it easy for women to screen for cervical cancer with a less intrusive self-sampling method (compared to a pap smear conducted by a health care professional), reduce overload on government clinics by directly sending women the test results, follow up if results are abnormal, and ensure they take the test twice more in their life by registering them in a database.

“I don’t think that’s a big ask,” said Dr Woo. “That’s a human right.”

Low-level community activities are currently conducted under the ROSE system, pending the launch of a ROSE foundation that is expected within a month, according to Dr Woo.

Cervical cancer is the third most common cancer in women in Malaysia, according to the Malaysian National Cancer Registry Report 2007 to 2011. Dr Woo said only 12.9 percent of women in Malaysia took a pap smear once in their life, usually after giving birth, while the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) target is 70 percent HPV screening coverage for women aged 35 to 45.

How ROSE works

For a start, the ROSE system will target patients at government clinics and ensure that they don’t unnecessarily take the HPV test every year by registering their IC number in a registry compliant with the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA). They only need to take it every five years where resources permit, while WHO suggests two tests a lifetime.

According to Dr Woo, the HPV test, which simply requires women to insert a swab into their vagina themselves, under ROSE’s 2017 pilot programme at government clinics was done for 50 to 60 patients daily, compared to just five pap smears that could be offered by these overloaded clinics that saw about 1,000 patients a day.

“We didn’t need a room, we didn’t need a bed, we didn’t need the staff. The women just registered and did it themselves behind a curtain,” said Dr Woo. “So the solution was very simple and can be incorporated in the clinics immediately.”

A woman simply registers for ROSE on her mobile with her IC number at the government clinic, gets instructions on how to do a self-test, and the test results come to her phone in less than three days.

In cases of abnormal results, the ROSE system enables patients to phone a ROSE-dedicated number and ask questions, after which they will be directed to a government hospital.

“What happens in most public healthcare facilities, whether it’s public hospitals or clinics, after a pap smear, the nurses tell them: ‘If you don’t hear from us, that’s good news’. But in their busyness, I have seen them slip through the net with abnormal results,” said Dr Woo.

“So what this solution or the registry does is it ensures it’s a closed loop for that particular woman. That’s essentially the ROSE solution.”

WHO director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus wrote a letter last January 8 to Dr Wan Azizah and Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad to commend the ROSE project.

“I especially endorse your women-centred approach through use of self-sampling coupled with HPV DNA testing as well as e-health technologies to minimise barriers to uptake of screening services,” he said in the letter sighted by CodeBlue.

When the system matures, Dr Woo proposed that the Health Ministry work with the National Registration Department so that ROSE can track all women upon hitting 35 and start the cervical cancer screening process for them.

For private sector patients, Dr Woo said ROSE did not yet target them, but suggested that the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) or the Social Security Organisation (Socso) reach out to them.

“EPF, at age of 40, they may be able to send out a letter or email or SMS that says, ‘Have your cervical screening done, wherever it is’.”

UM’s joint venture with VCS Foundation

Universiti Malaya launched last January a joint venture on the ROSE project with Australia’s VCS Foundation, a non-profit that works on cancer prevention, particularly cervical cancer. Researchers say Australia will be the first nation to effectively eliminate cervical cancer by 2035.

Dr Woo said the joint venture would be a social enterprise that provides free HPV tests, which are three times more expensive than pap smears, to under-served people in Malaysia, starting with Sabah and Sarawak. A pap smear costs less than RM50.

“When we execute it, we hope to collaborate with LPPKN (National Population and Family Board) and Klinik Kesihatan,” she said. LPPKN runs its own clinics.

Dr Woo expressed hopes of making the ROSE social enterprise sustainable, such as by selling the HPV test to private clinics or by providing consultancy or training services. She expected the ROSE foundation to be launched in a month, pending the completion of paperwork.

She planned for ROSE to play a similar role as VCS Foundation that operates a registry of participants of health programmes and manages screening and vaccination data for the state of Victoria in Australia.

“They’re legislated by the state to run the system, but the data belongs to the government,” said Dr Woo.

She said a registry was necessary for Malaysia to monitor cervical cancer follow-up for its population.

“So we need to legislate and make sure the policy is there to monitor. We’re not saying the whole exercise needs to be borne by the government. We’re just saying the government needs to legislate and monitor, but the private sector can do it.”

ROSE, she said, encapsulated data management, a call centre, education, and engaging with policymakers.

“ROSE will be with the patient and health provider every step of the way.”