Book Review

The Private Healthcare Sector in Johor: Trends and Prospects

Meghann Ormond & Lim Chee Han (2018)

Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute (47 pages)

This ISEAS monograph would be of special interest to regional (health services) planners and would-be investors in the private hospital and medical tourism industries.

The authors begin with useful background information on epidemiological and demographic trends, macroeconomic and health systems indices for the public as well as private healthcare sectors in Johor, against the backdrop of the regional development priorities of the Iskandar Malaysia (IM) special economic zone 1.

The state of Johor accounted for 11.9 percent of Malaysia’s population in 2016, 8.6 percent of private hospital beds nationwide, and 10.7 percent of private hospital admissions nationwide (2013)2. It is unclear whether this indicates a surfeit, or a dearth, in the supply of private hospital beds in the state, given that Johor ranks fifth in median monthly household income among the states and federal territories of Malaysia3.

But what is clear is that healthcare entrepreneurs in the hospitals and medical tourism industries have bought into the glowing projections of demand for inpatient services 4, in anticipation of the growth of the population of Iskandar Malaysia, touted improbably as Malaysia’s emerging Shenzhen – 1.5 million in 2006, projected to reach 3 million by 2025 (including many PRC nationals among the planned-for 700,000

residents of Forest City5).

Topped off by an expected influx of medical tourists from Singapore and Indonesia, this was supposed to catapult Johor into the ranks of Penang and Melaka as Malaysia’s premier medical tourist destinations.

The authors noted that beginning 1 March 2010, newly enacted legislation in Singapore allowed residents to use their Medisave funds on hospitalisation and day surgeries in selected Malaysian hospitals with an approved working arrangement with a Medisave-accredited institution or referral centre in Singapore… In the six months following the policy implementation, a significant proportion of Singapore residents pursuing care in Malaysia were doing so for obstetrics and giving birth. Others sought coronary angiograms, cataract surgery, total knee replacement and total hip replacement. However, the proportion of Singaporean “health tourists” in Johor appears to have remained relatively small since 2010.

How small?

…roughly half of all medical tourism in Johor comprises foreigners residing in Malaysia, while the other half comprises “health tourists”. Indonesians made up 90.5 per cent of all “health tourists” in Johor in 2015, while Singaporeans, the second largest group of “health tourists” in Johor, comprised only 4.3 per cent. The persistently small number of Singaporean “health tourists” has troubled the region. There were initially hopes that this number would grow in the wake of [the] Singaporean legislation…

A notable strength of this monograph was its differential tallies of “genuine” medical tourists as distinct from other foreigners who had not travelled to Malaysia expressly for the medical treatment that they nonetheless received (such as resident foreign workers, foreign students, foreign retirees, vacationing tourists, business travellers).

But there is a subtle nuance that may have escaped the authors, viz. Malaysian expatriates working and residing in Singapore, who still retained their Malaysian passports, and constitute, as permanent residents in Singapore, a special niche market of diasporic medical tourists6.

As patients in Johor’s private hospitals, were they counted as medical tourists by the collating and reporting systems for statistics on medical tourism? Or were they excluded (undercounted) from the numbers

reported for foreign nationals traveling to Malaysia expressly for the purpose of seeking medical treatment?

In 2017, the Singapore Department of Statistics recorded 526,600 permanent residents (PRs) on the island, without specifying their national origins7. In the census of 2010, 385,979 persons were recorded as

Malaysian-born residents in Singapore8, without specifying how many had become citizens of Singapore, and how many remained as PRs.

It is safe to assume that the number of Malaysian nationals who are working in Singapore as permanent residents, or as resident non-PR holders of work permits, are in the hundreds of thousands.

What about Forest City? Notwithstanding (temporary?) hiccups9, will this be a captive market of half a million resident PRC nationals accessing private healthcare at half the cost of comparable services in Singapore?

My anaesthetist brother-in-law who owns and operates a 20-bedded hospital in Kuala Lumpur, was approached awhile back by a PRC construction company interested in buying over his hospital to service the healthcare needs of their 40,000 work-force. Is this a sign of the times to come?

The monograph does not shed light on questions which public enterprise specialists may find intriguing, for example why the Johor Corp, alone among all state economic development corporations (SEDCs), achieved such prominence, through its Kumpulan Perubatan Johor (KPJ) conglomerate10, as a health services GLC (government-linked company)11. What were the contingent circumstances, if any?

To what extent was KPJ in competition with the federally-controlled IHH-Parkway Pantai chain of hospitals12? Would it have mattered if Johor had been retained by the Barisan Nasional coalition in the 14th General Election? Or vice versa?

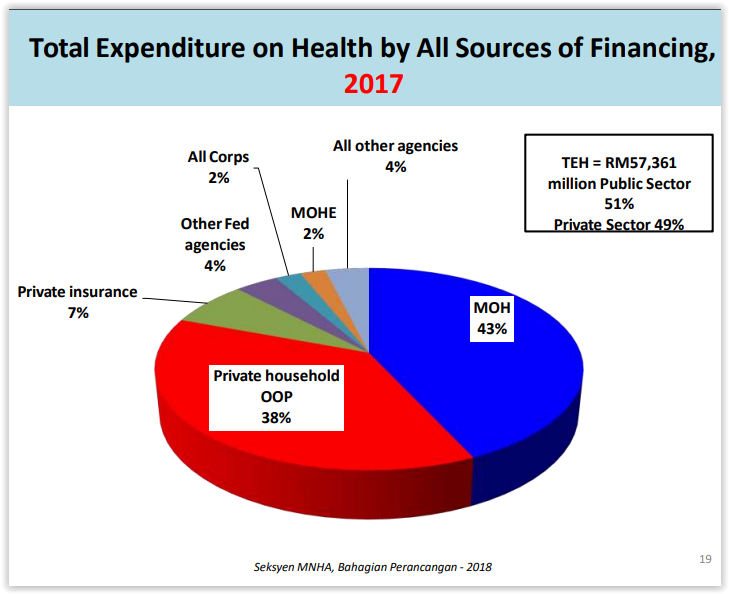

As Malaysia’s government-linked entities built up their stakes in the commercial healthcare sector, a succession of health ministers have argued – using a rhetoric of targeting – that Malaysians who could afford it should avail themselves of private healthcare services (suitably encouraged thus with income tax rebates, and hefty 1st class patient charges if they were subsequently referred to government health facilities).

This would allow the government to target its limited healthcare resources on the “really deserving poorer citizens”. This has much intuitive appeal, and indeed “targeting” is often the persuasive face and generic template for the commercialization of essential social services13.

Less obviously, a policy of selective targeting would detach a politically vocal, well-connected and influential middle class from any remaining stake in public sector healthcare, hastening the arrival of a rump, underfunded, decrepit public sector for the marginalized classes.

Is there an alternative to this emerging two-tier healthcare apartheid?

The Malaysian government’s answer to this is a putative national health insurance scheme which would eventually cover the entire population. This would probably entail employer and employee contributions to a publicly-managed health insurance fund (including the self-employed), along with patient co-payments and supplementary federal allocations, which would finance a defined benefits package.

Among other things, this Social Health Insurance (SHI) scheme was envisaged as a vehicle which could open up access to underutilized capacity and specialist expertise in the private healthcare sector, subject to a standard fee schedule applicable to all healthcare providers.

Would private facilities and private practitioners be allowed to opt out of the scheme, if they chose to concentrate on more lucrative niche markets (e.g. affluent patients, and medical tourists)? Or would they be prevailed upon to undertake their ‘national service’, given the pervasive public ownership of the for profit healthcare sector?

An alternative scenario, which relies on more progressive taxation regimes to expand and upgrade the public sector for universal access to no-frills quality care on the basis of need, which dispenses with much of the administrative and transactional costs of a parallel system for managing SHI enrollees’ contributions, its eligible pool of beneficiaries, and its provider payment systems, is notably absent from the options under consideration.

In this connection, the Health Ministry should perhaps take note of the recent work of Adam Wagstaff at the World Bank, who summarized thus his longtitudinal analyses of an OECD database spanning 1960-2006 and twenty-nine countries: “adopting social health insurance in preference to tax financing increases per capita health spending by 3-4 percent, reduces the formal sector share of employment by 8-10 percent, and reduces total employment by as much as 6 percent. For the most part, social health insurance adoption has no significant impact on amenable mortality, but for one cause – breast cancer among women – social health insurance systems perform significantly worse, with 5-6 percent more potential years of life lost”14

1 – Growing population spurs demand in Iskandar Malaysia https://www.nst.com.my/property/2017/04/232342/growing-population-spursdemand-iskandar-malaysia

2 – National Healthcare Establishment and Workforce Statistics (Hospital) 2012-2013, January 2015, Ministry of Health Malaysia

3 – Report of Household Income and Basic Amenities Survey 2016, Department of Statistics Malaysia

4 – https://www.straitstimes.com/business/companies-markets/patients-can-use-medisave-at-gleneagles-medini

http://www.regencyspecialist.com/patient-guide/for-singapore-patients-medisave/

5 – $100 billion Chinese-made city near Singapore ‘Scares the Hell Out of Everybody’ https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2016-11-

21/-100-billion-chinese-made-city-near-singapore-scares-the-hell-out-of-everybody

6 – this is a distinctive subgroup of medical tourists who are discriminating consumers of health services in their countries of origin, comfortable with a familiar linguistic and cultural milieu, with networks of family and friends, and therefore much less in need of agents or intermediaries to help them navigate the Malaysian healthcare system

7 – https://www.singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/population/population-and-population-structure/latest-data

8 – https://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/cop2010/cop2010adr

9 – China investors still bullish on Malaysian real estate

https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2017/08/28/china-investors-still-bullish-on-malaysian-real-estate/

https://www.ft.com/content/c30286c6-0563-11e7-ace0-1ce02ef0def9 China capital controls leave buyers of foreign property in bind

https://www.malaymail.com/s/1339591/china-capital-controls-leave-buyers-of-foreign-property-in-bind-video Forest City is not for foreign

buyers – PM http://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/forest-city-not-foreign-buyers-%E2%80%94-pm

10 – In 1979, the corporate arm of the Johor state government launched its first commercial hospital. Over the next 25 years, this inaugural venture grew into the largest chain of private hospitals in Malaysia, KPJ Healthcare (twenty-six hospitals in Malaysia, with another two in

Indonesia). Indeed, KPJ is now a publicly-listed healthcare conglomerate which offers not just inpatient care, but a diversified portfolio of services including hospital management, hospital development and commissioning, basic and post-basic training for nurses and allied health professionals, laboratory and pathology services, central procurement and retailing of pharmaceutical products, healthcare informatics, and laundry and sterilization services.

11 – GLCs are defined as companies that have a primary commercial objective and in which the Malaysian government has a direct controlling stake (i.e. ability to appoint board members, senior management, make major decisions for the GLCs including contract awards, strategy, restructuring and financing, acquisitions and divestments etc.) either directly or through government-linked investment companies.

12 – http://www.ihhhealthcare.com/about-overview.php

13 – Chan CK (2011) Aspects of Healthcare Policy in Malaysia: Universalism, Targeting, and Privatization. Global Social Policy 11:143-146.

14 – Adam Wagstaff (2009) Social Health Insurance vs. Tax-Financed Health Systems – Evidence from the OECD. Policy Research Working Paper 4821. Development Research Group, Human Development & Public Services Team, World Bank. Washington, DC: IBRD

This review was published in the Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 91, Part 2: 173-176.

Dr Chan Chee Khoon is a consultant and health policy analyst. He is a member of the Citizen’s Health Initiative.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.