Poliomyelitis (“polio”) made a comeback after 27 years when it was announced on 8 December 2019 that a 3-month old Malaysian boy from Tuaran, Sabah, was admitted to the intensive care unit with polio.

Subsequently, it was announced on 10 January 2020 that two unimmunised migrant children aged 11 years and 8 years in Kinabatangan and Sandakan were diagnosed with polio.

The polio virus strain in all three cases were found to have the same genetic relation to the strain in the Philippines outbreak in September 2019.

As all the three children had not travelled outside of Malaysia, it was very probable that they had contracted the virus from carriers who were not showing symptoms.

The last documented case of polio was in 1992 and the last outbreak in 1977 with 121 cases due to wild polio. The World Health Organization (“WHO”) declared Malaysia polio-free in 2000.

Immunisation coverage

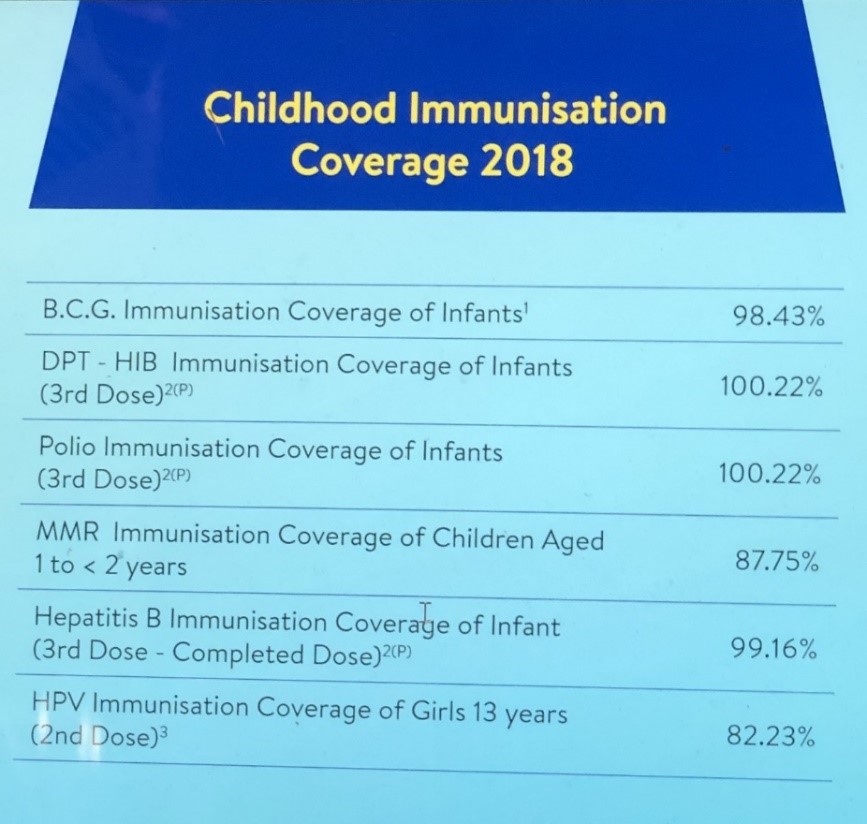

According to the Health Ministry, the immunisation coverage for polio for 2018 was 100.22%!

This data is questionable as mathematics teaching will have to radically change to get a percentage coverage of more than 100 per cent.

The more important question is whether the data included the children of migrant workers. The documented migrant workers numbered 2.7 million in 2017 with an estimated two to four million additional undocumented workers.

It is very unlikely that the Health Ministry data included that of children of migrant workers, as migrant workers have difficulties accessing immunisation for their children, resulting in many who are unimmunised.

The general consensus is that a population is protected against a disease when there is 95 per cent immunisation coverage.

As such, polio should not have occurred in Malaysia if it did indeed have the 100 per cent immunisation coverage, according to the Health Ministry data.

It is therefore evident that the Health Ministry data is fundamentally flawed with consequent impact on health policy and implementation.

There would be difficulty obtaining data of the children of undocumented migrant workers. However, what would the actual polio immunisation coverage be if it included the data of the children of documented migrant workers?

UNICEF’s warning

The Sabah Assistant Minister of Education and Innovation, who at the material time was a consultant with United Nations Children’s Fund (“UNICEF”), was reported to have stated that the Health Ministry ignored UNICEF’s call, five years ago, to immunise the undocumented population in Sabah.

“Figures from the Home Ministry state that there are some 500,000 undocumented persons in Sabah and 95 per cent of the children from this group had not been immunised…the health minister had responded that a fee of RM40 for registration and additional RM40 for one vaccine would be charged to non-citizens and the undocumented.”

Could the current polio outbreak have been averted had action been taken on UNICEF’s call five years ago?

Philippines cases

The Philippines Department of Health (“DOH”) declared a polio outbreak on 19 September 2019 with two cases caused by vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2). Environmental samples taken from a waterway in Davao on 22 August 2019 tested positive for VDPV2. In addition, VDPV1 was also isolated from environmental samples collected in Manila in July and August 2019.

The World Health Organization (“WHO”) announced on 24 September 2019 that it estimated that the risk of further spread within the Philippines was high due to “limited population immunity (coverage of bivalent oral polio vaccine (OPV) and inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) was at 66 per cent and 41 per cent respectively in 2018) and suboptimal AFP (acute flaccid paralysis) surveillance.

The WHO announced on 9 December 2019 that the case in Tuaran, Sabah, was a “rare strain of poliovirus called circulating vaccine-derived polio (cVDPV) Type 1. These polio viruses only occur if a population is seriously under-immunized. The Sabah polio case is genetically linked to the ongoing poliovirus circulation in the southern Philippines.”

The Philippines outbreak was reported about two months before the Tuaran case. Given the proximity of Mindanao to Sabah and the mobility of the populations, the question arises as to whether the Health Ministry responded to this red flag. Was preventive immunisation of all children in Sabah considered during this window of opportunity?

World Health Organization recommendations

The WHO’s Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (2005) held its meeting on 11 December 2019 at WHO headquarters. It was convened by the WHO Director General with members, advisers and invited Member States attending via teleconference.

The Committee reviewed the data on wild poliovirus and circulating vaccine derived polioviruses (cVDPV) and made recommendations to Indonesia, Malaysian, Myanmar, and Philippines.

The WHO’s press statement on 20 December 2019 was reiterated on 7 January 2020. “These countries should:

- Officially declare, if not already done, at the level of head of state or government, that the interruption of poliovirus transmission is a national public health emergency and implement all required measures to support polio eradication; where such declaration has already been made, this emergency status should be maintained as long as the response is required.

- Ensure that all residents and long¬term visitors (i.e. > four weeks) of all ages, receive a dose of bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine (bOPV) or inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) between four weeks and 12 months prior to international travel.

- Ensure that those undertaking urgent travel (i.e. within four weeks), who have not received a dose of bOPV or IPV in the previous four weeks to 12 months, receive a dose of polio vaccine at least by the time of departure as this will still provide benefit, particularly for frequent travelers.

- Ensure that such travelers are provided with an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis in the form specified in Annex 6 of the IHR to record their polio vaccination and serve as proof of vaccination.

- Restrict at the point of departure the international travel of any resident lacking documentation of appropriate polio vaccination. These recommendations apply to international travelers from all points of departure, irrespective of the means of conveyance (e.g. road, air, sea).

- Further intensify cross¬border efforts by significantly improving coordination at the national, regional and local levels to substantially increase vaccination coverage of travelers crossing the border and of high risk cross¬border populations. Improved coordination of cross¬border efforts should include closer supervision and monitoring of the quality of vaccination at border transit points, as well as tracking of the proportion of travelers that are identified as unvaccinated after they have crossed the border.

- Further intensify efforts to increase routine immunisation coverage, including sharing coverage data, as high routine immunisation coverage is an essential element of the polio eradication strategy, particularly as the world moves closer to eradication.

- Maintain these measures until the following criteria have been met: (i) at least six months have passed without new infections and (ii) there is documentation of full application of high quality eradication activities in all infected and high risk areas; in the absence of such documentation these measures should be maintained until the state meets the above assessment criteria for being no longer infected.

- Provide to the Director-General a regular report on the implementation of the Temporary Recommendations on international travel.”

A Health Ministry official stated on 27 December 2019 that it would not adhere to WHO’s recommendations for now. No reason was given.

Summary

In summary, answers are urgently needed for some of the pertinent questions the polio outbreak has thrown up.

Would the polio immunisation coverage data be reviewed and revised to include that of documented migrant children? Such revision would provide more accurate data to guide health policy and implementation.

Could the current polio outbreak have been averted had action been taken on UNICEF’s call to immunise the children of undocumented migrant workers five years ago?

Should immunisation be administered to all children of migrant workers, whether documented or undocumented? Communicable disease knows no boundaries. There is a human rights, public health, and economic case for every child to be immunised if we want to prevent communicable diseases from affecting citizens and non-citizens alike.

What has been the cost of containing the polio outbreak to date?

Now that three cases of polio have been reported to date, would the Health Ministry revise its previous decision not to adhere to WHO’s recommendations? If not, the question arises as to what factors will lead to a revision of its decision.

To attribute the polio outbreak to the migrant workers would be simplistic.

A constructive approach would view it from the perspective of immunisation coverage of the whole population.

Dr Milton Lum is a past President of the Federation of Private Medical Practitioners Associations, Malaysia and the Malaysian Medical Association. This article is not intended to replace, dictate or define evaluation by a qualified doctor. The views expressed do not represent that of any organization the writer is associated with.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.