KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 30 – A new report has shown further evidence of discrimination and xenophobia in public health care settings against undocumented persons who are denied treatment due to their status.

The Ministry of Health’s (MOH) Circular 10/2001 requiring all government health care workers to notify the police of undocumented persons seeking treatment at public hospitals and clinics is indirectly encouraging xenophobic attitudes among civil servants, according to the “Left Far Behind: The Impact of Covid-19 on Access to Education and Healthcare for Refugee and Asylum-seeking Children in Peninsular Malaysia” report by the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS) Malaysia and the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) Malaysia.

The report cited a lack of empathy among government health care and civil society workers, who refuse to provide treatment to refugees, suggesting they seek care at private facilities instead because of a lack of documentation.

This was exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic that fuelled xenophobic sentiments against refugees, particularly when they are unable to communicate or pay for their treatment.

Juita Mohamad, director of economics and business unit at IDEAS, called for the withdrawal of the 2001 MOH circular and the removal or reduction of non-citizen fees at public hospitals.

“The existence of Circular 10 increases the fear among refugees and asylum seekers, and acts as a deterrent for many to seek health care unless absolutely necessary,” said Juita, who spoke on behalf of the report’s health care authors at Diode Consultancy. “There are ethical implications for physicians too as it is in conflict with the motto of ‘do no harm’,” Juita added.

Circular 10 reasons that the MOH has alloted large provisions for the health and safety of Malaysian citizens, and that illegal immigrants take up a sizable portion of these provisions meant for Malaysians.

It was estimated that as of October 2000, over two decades ago when the circular was issued, the number of undocumented migrants were 402,150, with Sabah having the largest number of undocumented migrants at 250,000 or 62.2 per cent.

Sabah Health Department data at the time showed that 8.4 per cent of treatment given to the state’s undocumented migrants were inpatient care, and 22.2 per cent involved childbirth.

Health Needs Of Refugee And Asylum-Seeking Children

Although Malaysia is not a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, which safeguards the rights of refugees, it is party to the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and the 2006 UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), both of which protect the interests of refugee and asylum-seeking children.

Malaysia has also made several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) commitments in health care, education, and non-discrimination in a pledge to leave no one behind.

The report found that the health care needs for refugee and asylum-seeking children were unchanged during the pandemic as they were prior to the Covid-19 outbreak, based on survey and interview responses from a total 40 health care workers who serve Malaysia’s refugee and asylum-seeking populations.

These included common primary care presentations such as fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, and worms. This pattern was seen in boys, but child protection issues came up as one of the top three presentations seen among girls prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Respondents reported that the main health conditions that affected refugee and asylum-seeking girls included issues arising from child marriage, teenage pregnancy, child abuse, and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV).

For children with disabilities, similarly, malnutrition was reported as one of the top three presentations, while for children with no reported disabilities, malnutrition appeared as a common presentation but not among the top three that occurred prior to the pandemic.

The report noted, however, that while the nature of the presentations seen did not change significantly during the pandemic, the causes of morbidity did.

Health care workers believed that the main causes of morbidity were poor hygiene conditions, low parental health literacy, and inadequate information about parenting.

But complex stress and stressors from the refugee’s experiences and displacement journey, compounded by barriers, financial issues, and cultural displacement were described as major causes of morbidity that worsened during the pandemic.

Medical Costs, Fear Of Arrest Among Major Health Care Barriers

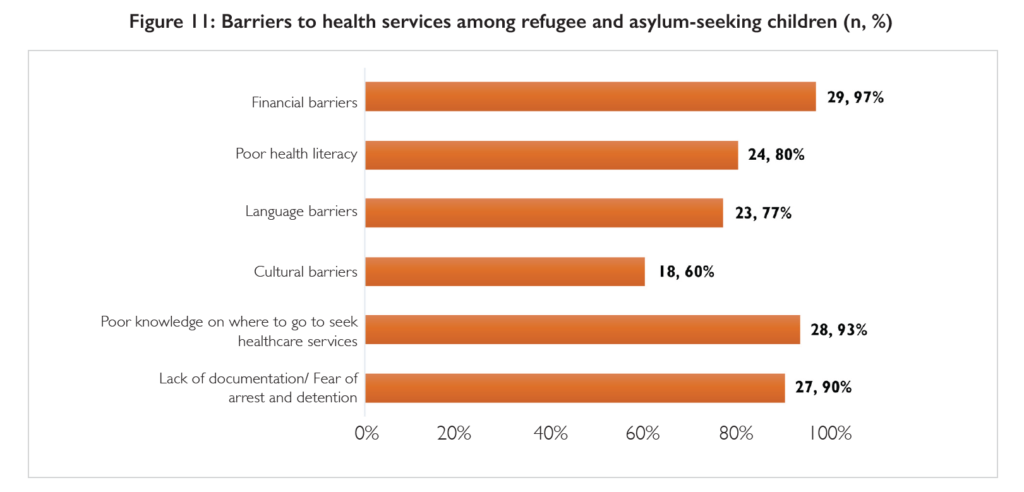

Barriers to health services for refugee and asylum-seeking children include financial barriers, sociocultural barriers, fear of arrest, inconsistent application of harmful policies, xenophobia and discrimination, lack of knowledge of health care services, and lack of state support.

Of all the challenges identified, cost was the primary barrier to health care access.

“Participants described this as a major and primary barrier to access to health care. These costs include cost for care, such as transportation, interpretation, testing and investigation treatment. And also admissions, multiple follow-ups and also multiple visits.

“Access to antenatal care, secondary care, and also childhood vaccinations is also quite limited due to the relatively high cost,” said Juita.

While countries such as the United Kingdom provide free medical services to asylum-seekers and refugees and their dependents, others like the United States opt to provide refugees with health insurance through Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Programme, and Refugee Medical Assistance, among others.

In Malaysia, refugees with UNHCR documentation are provided with a 50 per cent discount. This, however, does not offer much assistance after the government moved to double overall fees for foreign patients in 2016, according to the report.

The MOH further introduced a policy that limited medication prescription to foreigners to only five days, restricting the effectiveness of treatment for children by increasing cost-related barriers with the need for multiple follow-up visits.

Other major barriers to health care for refugees and asylum-seekers include fear of arrest, xenophobia, and sociocultural barriers such as language.

The report stated that while the risk of arrest is greater among undocumented immigrants, documented immigrants, too, risk arrest, particularly in the face of bribery and exploitation of those with documents.

According to Juita, the risk of arrest is linked to xenophobia and also health policies such as MOH’s Circular 10. “So being undocumented often led to the mistreatment and discrimination at different health facilities. And it also led to delays in seeking health care,” Juita said.

Health care workers surveyed in the study perceived cultural and language barriers to be the top two main sociocultural barriers in treating refugees asylum-seekers.

“During the pandemic, there were no legal options to hire interpreters from refugee communities, so there were no interpretation services in government services. There is also a lack of sociocultural sensitisation in NGOs and government facilities,” Juita said.

In addition to language barriers, 63 per cent of participants reported that public health care services did not employ appropriate child-friendly language when conducting health promotional activities.

And in the absence of case management services or interpretation support, children – especially unaccompanied children – struggled to access the health care system.

Juita also highlighted the lack of state support when it came to the availability of services for the protection of these children’s health.

According to the report, the Social Welfare Department (JKM) did not intervene in cases of child abuse, marriage or teenage pregnancy cases when it came to refugee and asylum-seeking children. JKM defended their inaction, saying such services are only for Malaysian children.

Juita described the view taken by JKM as having an “incorrect understanding and application of the Child Act 2001” which provides for all children in need of care and protection.

Policy Recommendations

In addition to the withdrawal of MOH’s Circular 10 and the reduction or abolishment of fees, the IDEAS-Unicef report also calls for the implementation of a health insurance or financing scheme that will allow refugees to contribute to their health care, ensure that health policies which apply to all are applied consistently and fairly, and applying the Child Act and the UNCRC, UNCRPD, and CEDAW to all children, among other things.

The report also suggests the establishment of networks and referral pathways for available services, having sensitisation workshops for health care workers to combat stigmatisation and discrimination, and deploying guidelines and best practices for NGO clinics to ensure they meet the needs of refugee and asylum-seeking children.

Meanwhile, targeted health programmes for specific needs can be created to not only aid refugee children but help all children living in Malaysia as it strengthens child protection and SGBV services.

This includes the establishment of case management programmes with health care facilities for all children, the provision of comprehensive care for all SGBV survivors that covers the understanding of trauma, and the expansion and deepening of existing multisectoral outreach services that target children at risk of abuse, the exploitation of children, and children with special needs.

The report also recommends continued strengthening of partnerships and coordination between refugee-specific health care service providers and health care workers in the public and private spheres, and the establishment of referral pathways from organisations offering health care for refugees to services offered by JKM.