After the Higher School Certificate (Form 6) examination, my school principal helped me to volunteer at the maternal and child health clinics for six months from 1970 to 1971 to help a British nurse, Sister Rose.

I spent the first three months in a Bidayuh village Benuk (Bunuk) in Padawan division, then a three-hour bus ride on a winding mud road from Kuching.

The second three months was in Mentu, an Iban longhouse in Samarahan division, a four-hour fishing boat ride to a coastal village, Sebuyau and another eight hours by open longboat upriver.

Both clinics had no electricity. We used pressure lamps when there was a patient for delivery. Normally only wick lamps were used, to save kerosene for the pressure lamps. The kerosene refrigerator provided by UNICEF allowed BCG, DPT and oral polio vaccines to be stored.

The Benuk clinic and simple house for us were in the same compound as the primary school. Shy curious children would come during the breaks to watch us. Ethnic Chinese and white women were rare in the rural areas in those days.

There were rain water tanks for water supply. To save water, we would take our bath and wash clothes in the little shallow stream by the house. The stream water was very cold but clean, except for the months when the farmers would soak sacks of pepper berries in the deeper sections, till the green skins can be rubbed off (to produce white pepper).

Patients would come to the clinic for simple medical conditions and bring their babies for weighing and vaccination. There was the occasional delivery on the wooden examination couch.

Most, however, preferred to call Sister Rose to the home for delivery than come to the clinic. The bus to Kuching was only once a day, and private transport expensive, so going to the hospital was not an option.

I remember once there was a serious flood cutting off the main road. A young man came to ask us to go and deliver his wife. We walked an hour to his village. In several long sections of the road, we had to wade waist-deep in flood water.

By that time, I had learned how to secure my sarong and could work/walk/bathe without the sarong slipping or floating off (jeans were not commonly worn then). We were careful to walk as far from the presumed sides of the road as possible. Flooded roadside drains have drowned even locals who normally could swim like fish.

We finally reached the little house on stilts. The kitchen floor had been cleared for the young woman in labour. We sat on the floor by the woman and read our books, waiting quietly till the time came. The shadows thrown by the flickering lights of the wick lamps and the jungle sounds of the dark night, interspersed with soft grunts of her deep pain was truly surreal.

As with all the rural deliveries I witnessed, there was no screaming nor histrionics. Somehow birth-pangs were so much part of life, native women endured labour pain without fuss. The first cry of the baby as it saluted the world lit up the woman’s face with such joy. In an instant, her long hours of pain vanished.

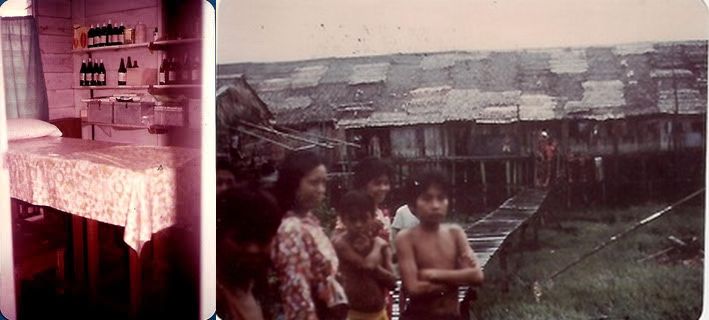

Benuk villagers, unlike Ibans, lived in more individualised houses on stilts. These were extensively connected by bamboo walkways and platforms which were used for drying padi and pepper and for gatherings like mobile clinics.

These walkways were raised above the ground at the level of the houses. They do have some sort of side support – like a single bamboo, more for psychological than structural support. It was not too high of a fall (10 feet?) but the ground below is normally soggy with droppings from humans and freely running pigs and poultry. A soft messy landing indeed, with tons of bacteria to infect the wound should one sustain a fracture!

When we set up clinic (on the open platform) usually at the headman’s house, women would bring their children for check-up and vaccines.

Mentu clinic in Ulu Sebuyau was very similar in its remoteness. The house we stayed in was up a hill from the clinic. There was a flush toilet in the clinic, but our house only had a surface toilet, some planks over an open pit in a little shed a distance away.

Snakes like sheltering in such outhouses. I was advised to carefully shine a torchlight around before use. Apparently, if there are reflections back from a pair of eyes, you should be able to tell if they belonged to a frightened frog or an annoyed snake. From the colour of the eyes or something – I never want to scientifically prove this. I preferred to train my bowels to clinic hours only.

Life was very basic. The nearest floating retail shop was an hour down-river by paddling our little boat. For simple things like sanitary pads, we did what the locals did – recycling pieces of old sarong and washing them out to reuse.

We had a vegetable patch to top up the wild ferns or leaves we could pick freely from the jungle. Every evening we would go there before taking a bath in the river in our sarongs.

The young men in the village love to “mandi jepun” (i.e. totally naked) in the deeper parts of the river. It seemed the most natural thing in the world for these strapping naked young men to stand there (with hands covering where the proverbial fig leaf should have been) and greet us “kini seduai?”. “Where goes thou?” in Iban is about as universal as “have you eaten?” in Chinese. They were not being intrusive, just polite and friendly.

There was no electricity nor TV. Children love to come and watch us. I practiced my Iban on them, whatever I was learning word for word from the Iban translation of the New Testament and a dictionary.

Invariably, they would fall about in fits of giggles, like I had just told the best joke in the world. They would endlessly repeat the words till I got them right. I owe my Iban fluency to them.

I had perhaps my first sense of heavenly intervention in Mentu clinic. A young man ran to tell us that he heard my name being called over the Radio Malaysia Sarawak to attend an interview for a federal scholarship for Medicine in a few days. We had no radio at the clinic and I would have missed the announcement and interview!

The mission nurse and I had to paddle our boat to buy petrol for the outboard engine at the nearest floating shop (we lost one of the paddles half way). It was an hour by outboard engine to the next village, a two-hour walk to the Pantu bus stop to wait for the once-a-day bus about six hours to Kuching. My mother could not recognise me when I turned up, in my sarong, but in time for the scholarship interview.

I was one of four in Sarawak awarded the Colombo Plan Scholarship for Medicine in Canada that year. Unfortunately, after my Higher School Certificate (HSC) results, these were withdrawn, presumably because too many medical scholars never returned to serve their country after graduation.

Despite excellent HSC results, my family was too poor to send me to university. My father said “it’s okay, you can go to the Batu Lintang Teachers training college”.

I got the scholarship for medicine in the University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur.

Dr Tan Poh Tin, proudly Sarawakian, is a paediatrician and public health specialist. She says: “Sarawak – to know you is to love you.”

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.