KUALA LUMPUR, June 5 – Parliament’s health committee leader Dr Kelvin Yii today warned the government that the current medicine shortage would likely rip through the entire health care system due to global supply disruptions, unlike previous perennial shortages.

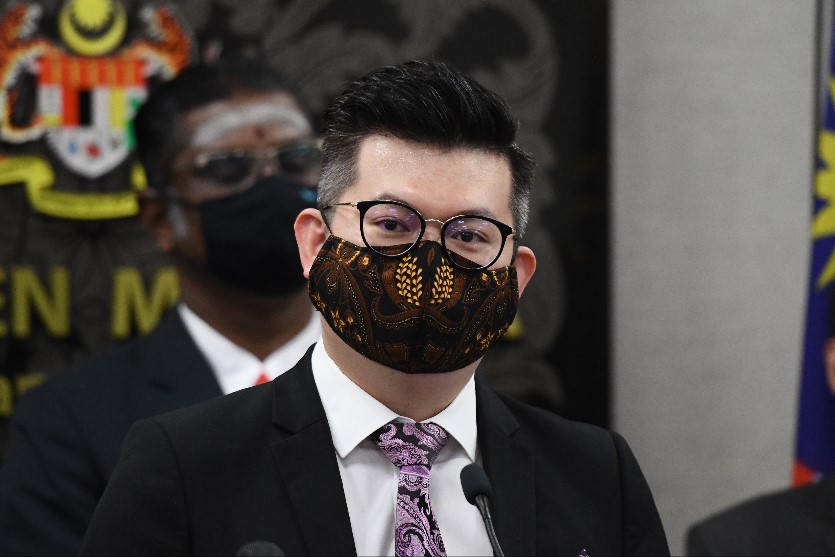

Dr Yii, who chairs the Dewan Rakyat health, science and innovation committee, told the government to take the current medicine shortage seriously, highlighting Malaysia’s vulnerable position as a net importer of pharmaceutical products.

He cited world trade experts who believe that it will take up to a year for global supply chains to get back to normal, following the Covid-19 pandemic and China’s recent two-month lockdown in the commercial hub of Shanghai.

World trade expert Vincent Stamer told German news outfit DW last month that he expects global supply chains “won’t get back to normal this calendar year”, as port and shipping bottlenecks are difficult issues to resolve. He added that some “easing” should be seen in the next 12 months, but only if China doesn’t impose further lockdowns in its zero Covid policy.

“This issue is slowly rippling through the system now, and it’s only a matter of time before the public really feels it, especially once the stockpiles are gone, including generic drugs, then it may be too late to do anything,” Dr Yii said in a statement today.

“While the Ministry of Health (MOH), including Deputy Health Minister Datuk Dr Noor Azmi Ghazali has come out to downplay the seriousness of the issue and the shortage of medicines is under control, this issue cannot be taken lightly as these shortages are unlike previous shortages, as this will hit the entire health care system, both public and private, since it’s a global supply issue.”

While Malaysia has always had minor medicine shortages in the public health care system towards the end of the year, such as cancer drugs, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused massive disruptions of global supply chains that were worsened with harsh lockdowns in China this year and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war.

Dr Yii told MOH to spell out clear short-term, mid-term, and long-term policies to mitigate the impact of the current medicine shortage on the health care system.

The DAP health spokesman suggested that the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA) immediately undertake an extensive audit and stock count of all pharmaceutical stock across public and private health care facilities to understand the full extent of the country’s medicine shortage.

“It is also important they determine manufacturing capacities of manufacturers, turnover rate, and stock holding.”

He added that local and multinational pharmaceutical manufacturers must ensure sufficient manufacturing capacity of both innovator and generic drugs tor stockpiling.

“Then, I believe MOH should compel concession companies, such as Pharmaniaga and other central contracts companies, to prioritise their stocks and supplies to MOH facilities, where more than 70 per cent of the general population goes to.

“Such supplies should then be properly distributed based on a ‘ring strategy’ to ensure areas of highest needs get them first.”

The DAP health spokesman said MOH could also issue an advisory to health care providers to begin rationing certain medicine supplies now to buffer against the high likelihood that current stockpiles may not be enough.

“Wastage of medicines should also be reduced by reconsidering prescription quantities and duration upon patients being reassessed.”

Dr Yii told the government to consider exploring new pharmaceutical markets in other countries for alternative suppliers and brands of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs manufactured in Indonesia or Egypt.

“Such arrangements can be done through import permits to ensure adequate supply in our country for the time being.”

China is the world’s number one supplier of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and pharmaceutical intermediates – components required to produce medicines.

Over the long term, Dr Yii said the government should plan a national medicine security strategy to boost local production of APIs, as Malaysia’s entire supply of finished pharmaceutical products is either directly imported, or indirectly imported for local manufacture via the import of APIs.

“While this likely is a temporary issue, but how temporary it will be is still unknown and when it comes to essential items such as medication, it must not be taken lightly.”

Private hospitals and general practitioner clinics have complained about a shortage of medications like antibiotics and OTC drugs for fever, flu, and cough and cold, including paediatric medicines, such as cough and flu syrups for children.

Local pharmaceutical suppliers attribute Malaysia’s current medicine shortages to the recent China shutdowns and the Russia-Ukraine war that exacerbated global supply challenges sparked by prolonged global lockdowns during the past two years of the pandemic, amid a surge of local and global demand as countries reopened this year.

The Malaysian Association of Pharmaceutical Suppliers (MAPs), which represents local pharmaceutical importers, projects Malaysia’s medicine shortage to worsen and spread across all therapeutic segments. Suppliers told private medical practitioners to expect shortages of raw materials for medications to continue until September or until the end of the year.