KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 4 — Physicians have questioned why the Ministry of Health (MOH) does not negotiate with pharmaceutical companies for lower drug prices, instead of rejecting outright expensive treatments.

They pointed out that the United Kingdom and even Thailand frequently negotiate with drug makers for cheaper prices.

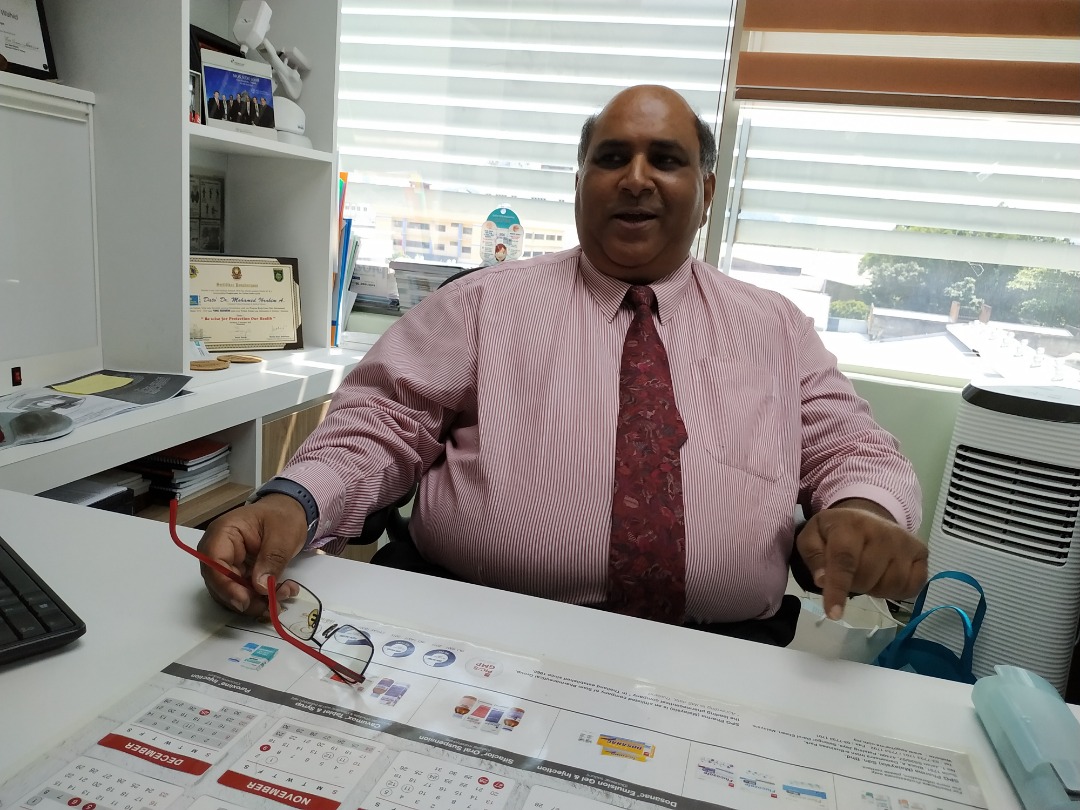

“The problem with the Blue Book and the government system is, like you say lah, you don’t know what happened to it. The thing gets submitted, you look at it, and they say ‘mahal sangat, cannot afford, reject’. The problem is they never negotiate,” Beacon Hospital medical director Dr Mohamed Ibrahim Abdul Wahid told a recent forum on advanced breast cancer organised by the Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy here.

The Blue Book refers to MOH’s formulary that lists drugs which MOH routinely pays for and provides in its facilities. Public university hospitals have their own individual formularies.

“So if actually they turn around and say, ‘Look, you charge me RM10,000 for, let’s say Herceptin (trastuzumab), cannot afford. But if you charge me RM4,000 for Herceptin, I might consider listing it for Blue Book for, you know, 100 patients or 200 patients. And this is my budget at RM4,000 for 200 Herceptin patients a year, or X number of doses a year’,” Dr Ibrahim added, referring to a targeted therapy for cancer.

“And that throws the ball back at the drug company and lets the drug company then make the decision whether they want to cut down that price. If they really desperately want to put the drug in the Blue Book, they can.”

Dr Ibrahim, a consultant clinical oncologist who used to sit on the Blue Book committee 10 years ago, said the problem is that pharmaceutical manufacturers don’t know what is MOH’s budget or how much it’s willing to pay for medicines.

“The system is so inflexible and it’s so rigid that they actually tie themselves in a very difficult situation.”

According to Dr Ibrahim, Beacon Hospital has established a corporate social responsibility programme since 2010 to provide discounts to low-income patients and those with insufficient medical insurance who undergo radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy. The original trastuzumab targeted therapy is given to breast cancer patients for only RM2,500 per cycle in a buy-one-free-one subsidy programme, with the original cost ranging between RM7,000 to RM8,000.

“We do have access to new and innovative drugs — they help cancer patients survive, like immunotherapy for lung cancer. Those days, you survive three to six months, they said ‘go home and die’. But today, with all the targeted therapy, things have advanced. Now, almost one-third of patients are surviving five years,” he said.

MOH is currently pushing for price regulations on innovative drugs, even though pharmaceutical multinational corporations have warned the government that this could affect their investments into Malaysia.

National Cancer Society of Malaysia (NCSM) medical director Dr M. Murallitharan said that even though MOH claims to provide good coverage of medicines, the newest treatments, 20 to 25 per cent of drugs, are not available in MOH hospitals. And the medicines that are provided in these government hospitals have limited availability in a “quota” system.

“So if you get cancer in January, you’re better off. There’s still quota, you can get the drugs. If you get cancer in June, July, August, September, unlucky you get in October, you better pray until January next year. This is, unfortunately, the truth,” Dr Murallitharan told the forum.

According to the public health physician, drug makers submit their products for listing on the Blue Book based on the medicines’ effectiveness, safety, and “the only dimension that matters seemingly for MOH, which is the cost of the drug”.

He also complained about how MOH doesn’t explain their rationale in refusing to fund certain treatments.

“They always just reject. So you don’t know, you’re going to the mountain, looking up to the gods, and you’re just praying when you submit the new drug. You don’t know if the cost is too high, too low. Nobody knows. They just come back reject.

“Or even worse, another common strategy, they’ll just be quiet, ‘don’t know, don’t know, don’t know. Not yet meeting, not yet meeting, not yet meeting’.”

“Price is not everything.”

Dr M. Murallitharan, National Cancer Society of Malaysia medical director

Dr Murallitharan also explained that various public university hospitals under the Ministry of Education (MOE) have their own separate formularies to decide which drugs they want to provide, such as UMMC, Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia (HUSM), and Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (HUKM). UiTM and Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) are also opening public hospitals.

“It’s a slow uptake process into the formulary. They have their own process and waiting time before a drug gets approved. Again, the problem is this whole control mechanism. Whether I want to put it into my version of my Blue Book, whether it’s MOH or MOE, is always based on cost.

“Moment someone says no budget, don’t approve into the Blue Book. It’s a very blunt edged sword.”

He said while public university hospitals give patients the option of buying medicines from outside, this is not practiced in MOH hospitals to avoid putting pressure on patients.

Dr Murallitharan pointed out that the UK has plenty of successful direct negotiations with drug makers on originator medicines that are produced by only one manufacturer.

“Under this new Malaysia Baru, people are scared to negotiate directly. In different countries, very successful direct negotiations have been done,” he said.

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends which medicines the NHS should fund based on the treatments’ effectiveness and value for money, unlike in Malaysia where MOH decides which drugs it should pay for in its own facilities.

Dr Murallitharan said not all drugs can be substituted with generics and biosimilars may sometimes only be 30 to 40 per cent cheaper than innovator medicines.

“What do we do in the meantime? A big stakeholder in the Ministry Of Health’s cancer control division told me, ‘It’s okay, we’ll just wait for all the drugs to be generic’.

“So in the meantime, it’s 10-15 years, so everyone just mati lah.”