If there’s a lesson to be learned from the entire MySejahtera chain of events, it is that public health is grounded in trust.

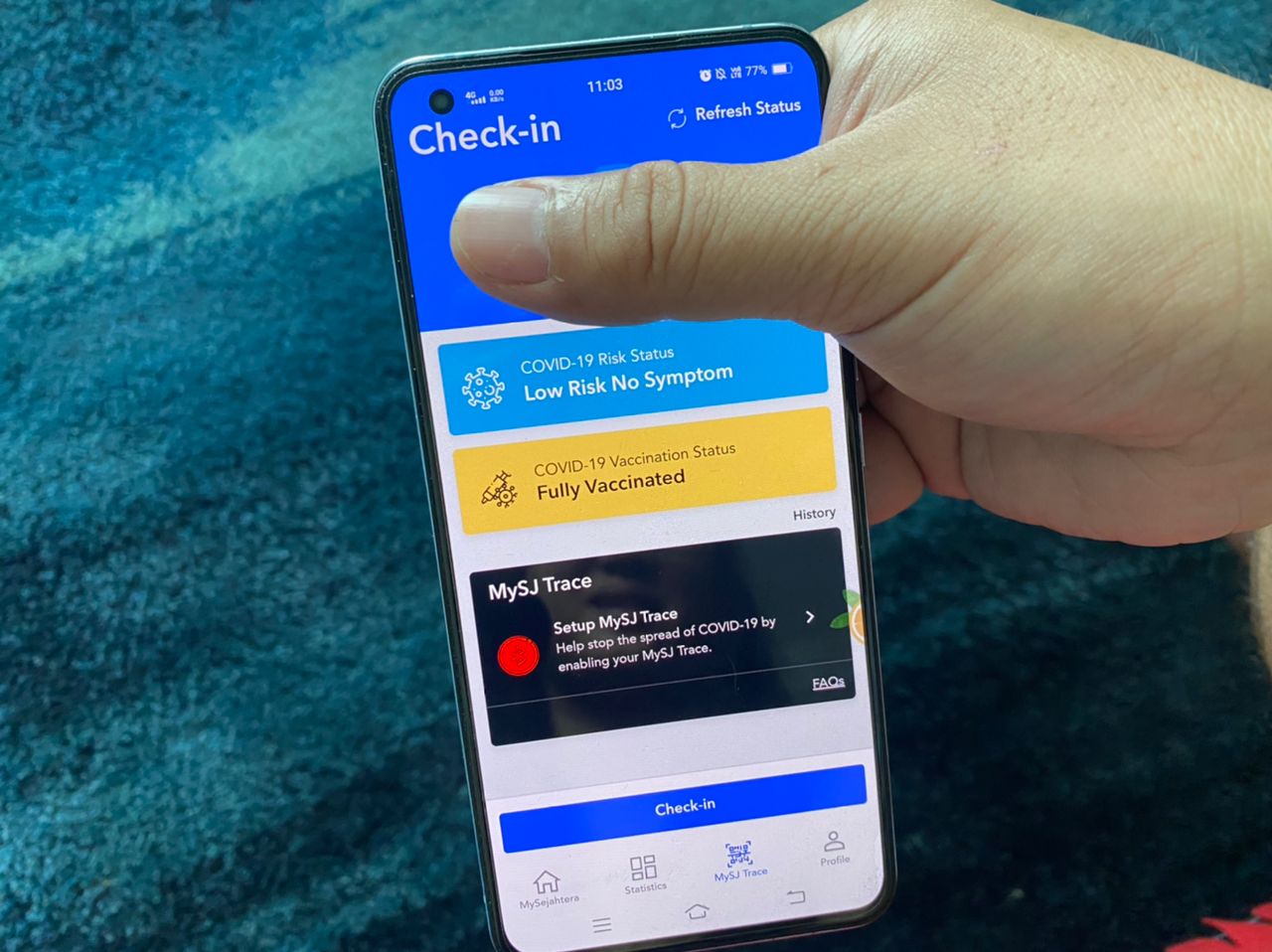

What is, no doubt, a Covid-19 app that was painstakingly built and has amassed 38 million users over the past two years of the pandemic, can be deemed irrelevant overnight with the erosion of trust, marred further by the public’s eagerness to put Covid rules behind them.

It took only two days for daily MySejahtera check-ins to fall by millions after controversy broke out, another two weeks before it declined further by 30 per cent, and just over a month before the government appeared to have succumbed to public pressure to lift check-in conditions.

The number of unique users checking in on MySejahtera fell 97 per cent from a high of 11.6 million last November 3 to about 309,000 on May 15 this year. About 113,000 of the 309,000 unique users are based in the Klang Valley with an estimated 8.4 million population.

Despite visible signs of waning trust in MySejahtera, the government seems adamant to push ahead with longstanding plans to expand the use of the app beyond Covid, with the end goal of making it more deeply entrenched in public health.

While there is an eventual need for a seamless electronic medical record system and a more real-time approach to monitor non-communicable diseases (NCDs), policies alone, no matter how good their intent, are not self-executing – they need to be followed and trusted to work.

The government, or the Ministry of Health (MOH), in particular, doesn’t seem to understand the importance of getting public trust, confidence, and buy-in when it comes to personal data and what more, unique individual health records.

The government’s cavalier attitude with our personal data – not putting a contract in place from the start, allowing DMs (direct messages) of private medical data to unverified social media accounts, and an apparent “confusion” over the appointment of the app’s developer KPISoft Malaysia Sdn Bhd (now Entomo Malaysia Sdn Bhd) – not only allows the “cancer” of mistrust to spread, but reveals a standard way of doing things that is rotten to the core.

Even if current Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin manages to broker a “lower priced” deal with Entomo or MySJ Sdn Bhd, there is no guarantee that his successor will not reject any commercialisation proposals as mooted before – what more with MySJ shareholders and Entomo embroiled in not one, but two potentially prolonged and expensive legal disputes.

As it stands, there is no clear indication that the MySejahtera debacle will die down. To many, the government mandated Covid app has been greatly compromised.

In fact, carrying the MySejahtera baggage risks creating an even more chronic perception that threatens to undermine MOH’s other public health efforts, including mask mandates, contact tracing efforts, Covid reporting, home surveillance orders, and a potential fourth Covid vaccine shot, as the country moves into a new phase of the pandemic.

Not only should the government develop or contract a new app to replace MySejahtera, with proper terms and legislations in place, the public should also be educated on digital health.

With trust in the deficit, the federal government should go the extra mile to regain public confidence by being transparent and not undermine the public’s intellect by hiding behind broad and outdated grey area laws.

The public needs to understand what digital health means, going forward, as the app’s legitimacy lies in public consent. Any form of top-down coercion is unethical.

A new government health app, done right, may not have 38 million registered users, but it will mean keeping the bigger national digital health agenda alive.

Editorials represent the views of CodeBlue as an institution, as determined through debate in the newsroom. CodeBlue’s Editorial Board comprises editor-in-chief Boo Su-Lyn, and health writers Alifah Zainuddin and Kanmani Batumalai.