Increased testing is probably one of the most crucial tools of non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) due to substantial asymptomatic transmission in Covid-19.

According to the latest estimates, asymptomatic individuals are responsible for transmitting close to 60 per cent of all infections. Therefore, only by ramping up testing capabilities can countries capture wider circles of asymptomatic cases, asymptomatic case contacts and individuals without obvious exposure.

Furthermore, test results prompt individuals to self-isolate, inform health officials about the pandemic state and guide policymakers in their decision to deploy other NPI strategies such as closing/opening schools, various economic sectors, etc.

The reported daily new infection cases do not even begin to tell the story. Epidemiologists continuously warn us that the number of detected cases is lower than the number of actual cases. The main reason for that is testing limitations.

Therefore, the daily number of confirmed cases combined with the daily number of tests, or rather the dynamic of their proportion over time, may begin to inform us how Covid-19 transmission and containment management unfolds in the actual population.

There are few ways to look at the dynamic of daily confirmed cases vis-à-vis daily new tests. One method is so-called per cent positive or test positivity rate — simply the percentage of tests that return positive, which is calculated as (positive tests)/(total tests) x 100 per cent.

Some scientists prefer using the opposite metric — test-to-case ratio calculated as (total tests)/(positive tests) and indicating how many tests it takes before one of them return positive.

However, it is crucial to understand that what matters is not only how many people being tested but also who have been tested.

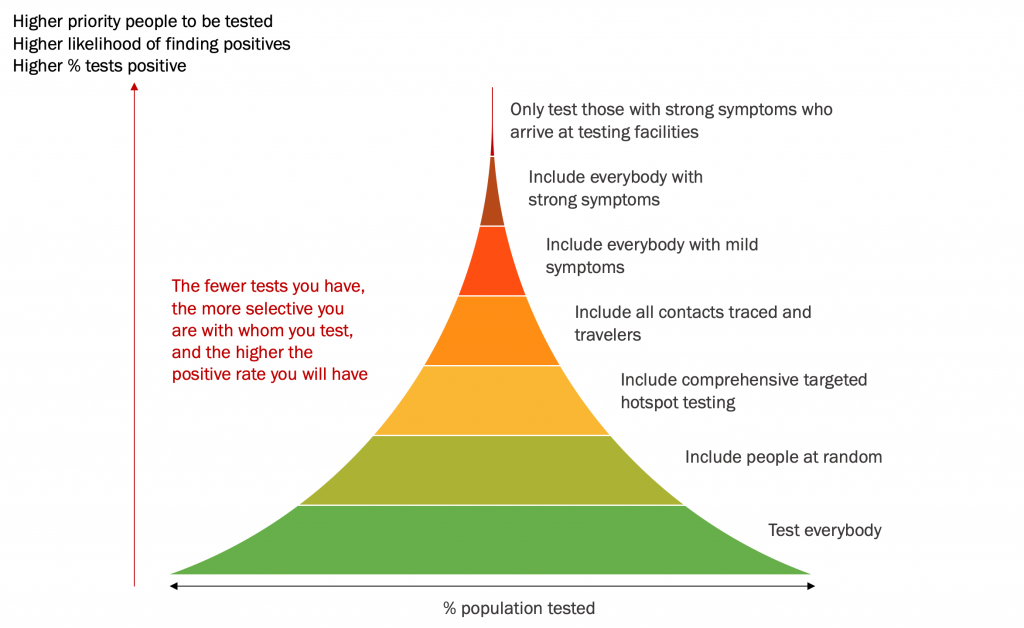

Understanding various categories of those who can be tested and who are most likely to be tested (Figure 1) brings us an understanding of why epidemiologists recommend keeping test positivity rate low and how it can be achieved.

High test positivity may indicate that those are mainly tested who are more likely to turn out to be positive — for example, people with strong or mild symptoms who themselves arrive at testing facilities or close contacts.

In other words, high test positivity indicates that testing is not wide enough to capture those who might not even know they are infected (asymptomatic and presymptomatic cases).

At the same time, a too-high test positivity may indicate the too-wide spread of infection in the community — meaning no matter how much you increase the number of tests, including even random people, if the spread in the community is too wide, low values of test positivity may not be achievable.

Thus, in any case, a high positivity rate implies inadequate pandemic control.

It is the pertinent question: what should be a benchmark positivity rate? The World Health Organization (WHO) currently suggests that the positivity rate should remain at 5 per cent or lower for at least two weeks before a region under the surveillance can be considered for reopening.

However, more recent discussion in the scientific community based on the experience of countries worldwide suggests that rates as low as 1 to 3 per cent would be a better indication of the pandemic being under control.

In a methodologically rigorous worldwide study conducted by Dr Ravindra Prasan Rannan-Eliya, the executive director of the Institute for Health Policy in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and his team, the researchers found that of all NPI measures, the testing intensity was the most influential and was highly statistically significant.

Dr Ravindra and his colleagues also found that almost all countries that reduced transmission to levels compatible with elimination were testing at test-to-case ratio levels of 100 and above, equivalent to test positivity rate one per cent and below.

As a policy recommendation, the researchers then suggested the following. At test positivity rate as low as one per cent and below, when the virus is close to elimination (the reproduction number is substantially below one), increases in testing could be traded for relaxing other interventions, such as school and economic sector closures.

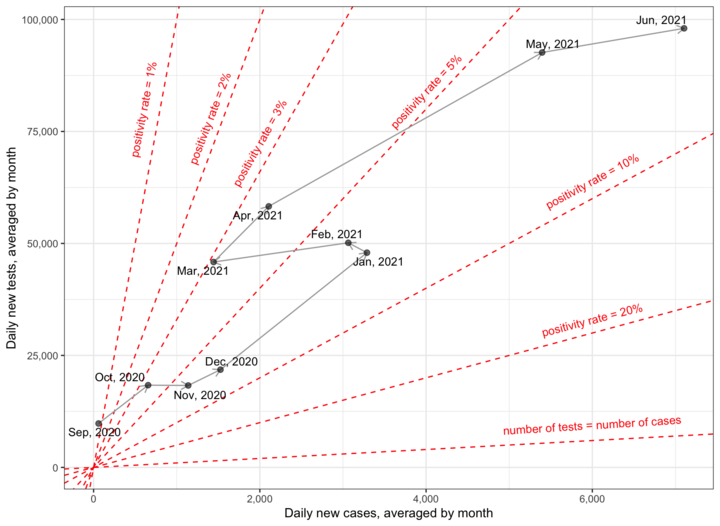

The graph below plots Malaysia’s daily new cases versus daily new tests (both averaged by month to declutter the chart) from September 2020 till June 9 2021. The dashed red lines indicate various levels of positivity rates.

As we can see from the graph, Malaysia’s positivity rate was below one per cent only until September 2020 (to be precise, until two weeks before the Sabah election). Already in October 2020, we have crossed above three per cent, and in November 2020 above five per cent.

This was the time when according to science, we should have immediately ramped up the testing volume multiple folds to get the pandemic under control which would be much more feasible when our contact tracing and healthcare facilities were not overwhelmed yet.

However, we can see that daily tests remained well below 25,000 on average, and only in January 2021 were increased two folds.

During Phase Five, which lasted from January 1, 2021 till March 31, 2021, when certain states with high Covid-19 cases were placed under MCO 2.0 from January 13, 2021 till March 4, 2021, the positivity rate gradually reduced to just above three per cent, indicating that the pandemic was being brought under control.

And again, the testing volume should have been much higher even at that time. Also, given the still relatively high positivity rate, any SOP relaxation should have been carefully considered.

Instead, the Ramadhan bazaar and Terawih prayer relaxation came as untimely jeopardies, with positivity rate measures spiralling out of control ever since.

As of now, Malaysia’s positivity rate is still hovering around seven per cent, and therefore, recently observed new daily case reductions should not be interpreted outside this alarming context.

Only a falling positivity test rate observed while maintaining or increasing testing volume can be seen as a bit of good news.

The above data visualisation indicates that Malaysia has never tested its population wide enough, at least since September last year.

The reality might be even gloomier when we consider that the above graph is based on data that includes not only PCR tests but also rapid antigen tests, when it is generally recommended to include only PCR tests in positivity rate calculations.

It is understood that government health authorities made decisions within given constraints — financial, technology, human resources etc. However, given the strategic importance of testing volume, as worldwide experience over one and half year with the pandemic indicates, we might want to ascribe a higher priority to it — next to probably only fast-tracking the national vaccination programme.

Importantly, even New Zealand, which could be rightfully considered an outlier with its outstanding ability to nearly eliminate the spread of Covid-19 in its community, continues testing its population extensively to date.

As Our World in Data site states, “Without testing, there is no data. Testing is our window onto the pandemic and how it is spreading.”

Without sufficiently wide testing, not only in terms of numbers, but also going far beyond close contacts, we are stumbling around in the dark.

Our decisions might be inadequate, and we might be sending the wrong signals to the public, thus unwillingly inciting complacency.

On the contrary, transparent reporting of the figure pertaining to the positivity rate (including the breakdown by the type of tests performed and geographic locations) could help us to acquire more stable prevalence information, make better decisions and bring more coherence to cooperation among various levels of our society in fighting this pandemic.

Rais Hussin and Margarita Peredaryenko are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.