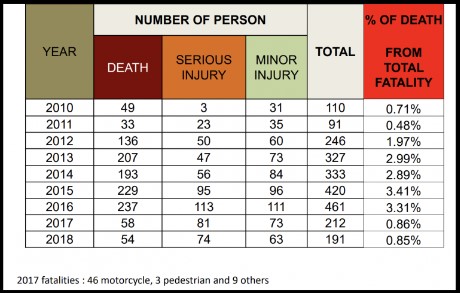

Civil liberties are tricky, especially in Malaysia that tends to have excessive State intervention in social and business spheres, regardless of the government of the day. Nowhere is this tested more than in the grey issue of consuming alcohol that has been intertwined with the emotive problem of drunk driving, despite drunk driving only contributing less than 4 per cent of fatal road traffic accidents annually between 2010 and 2018.

According to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, the proportion of drunk driving in fatal road traffic accidents in Malaysia ranged from a low of 0.48 per cent (33 cases) in 2011 to a high of 3.41 per cent (229 cases) in 2015. This dropped to 0.85 per cent (54 cases) in 2018.

Cilisos reported that drunk driving accidents comprise a low proportion of total road traffic accidents in Malaysia that range from 450,000 to 570,000 annually. Yet, instead of tackling real road safety issues underlying the hundreds of thousands of yearly road traffic accidents, our government and lawmakers – across the Pakatan Harapan and Perikatan Nasional administrations – train their myopic view on the fewer than 500 annual drunk driving crashes.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Malaysia has the third highest fatality rate from road traffic accidents in Asean and Asia, behind Thailand and Vietnam, with physician Dr Milton Lum saying that Malaysia’s road traffic fatality rates are similar to those of some African countries. WHO’s Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018 found that Malaysia recorded a 23.6 per 100,000 road traffic death rate in 2016, or 7,152 reported road traffic deaths, compared to single-digit fatality rates in developed countries.

The WHO report said road traffic deaths in Malaysia involving alcohol comprised less than 1 per cent of fatalities.

More than half of road traffic deaths in Malaysia involve motorcyclists, according to a 2012 study that reported only 75 per cent of motorcyclists involved wore helmets. Road accidents (5.4 per cent) were the fourth most common cause of death in Malaysia in 2016, behind ischaemic heart disease (13.2 per cent), pneumonia (12.5 per cent), and cerebrovascular disease (6.9 per cent).

Even if policymakers want to ignore the bigger public health picture of Malaysia’s deadly roads by focusing myopically on drunk driving, the Road Transport (Amendment) 2020 Bill passed by the Dewan Rakyat does nothing to address drunk driving. There is no evidence that harsher punishments deter intoxicated people from making the impaired judgment of getting behind a wheel. Instead, as the Malaysian Bar says, the revised law will cause “disproportionate” emotional and financial hardship for the families of convicted offenders.

The Bill incomprehensibly treats the act of killing someone from reckless or dangerous driving as a lighter offence (punishable with five to 10 years’ jail), than causing injury from drunk driving that is punishable with seven to 10 years’ jail. The Bill also imposes a heavier penalty for causing death from drunk driving with 10 to 15 years’ jail, compared to causing death from reckless or dangerous driving with five to 10 years’ jail. Why should both types of driving be treated differently when they result in the same outcome – death?

Finally, the minimum seven years’ imprisonment for causing (any) injury from drunk driving is completely disproportionate to the offence when you compare it to legislation for other crimes that cause physical harm, like voluntarily causing grievous hurt that is punishable with maximum seven years’ jail and fine.

So, lawmakers are basically saying that intentionally dismembering someone is a less serious crime than bruising one unintentionally in a drunk driving accident.

Even causing death by negligence is only punishable with up to two years’ jail, or a fine, or both. Voluntarily causing hurt only gets a maximum one-year jail sentence, or up to RM2,000 fine, or both. Basic principles of criminal justice dictate that death is more serious than injury, and that intent matters.

Rather than focus on long jail terms (which were already significant in the original Road Transport Act with minimum three years’ jail for causing death while drunk driving), policymakers should look at various policies to prevent driving under influence, such as publicising sobriety checkpoints, as recommended by the US’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The aim is to prevent one from getting behind the wheel while intoxicated in the first place, not to “catch” offenders in the act of drunk driving. Or Malaysian policymakers could think about how to work with ride-hailing companies to provide rides to people after drinking, as some ride-hailing drivers may be reluctant to pick up drunk passengers. The government should also promote a culture of designated drivers and carpooling, like in developed countries.

The haste in passing the badly drafted Road Transport amendment Bill, however, shows that the government isn’t really interested in resolving overall road safety issues, or even drunk driving. Lawmakers were simply caving in to pressure from religious fundamentalists who are intent on imposing their way of life on other Malaysians with different lifestyles.

Drunk driving, and purported health and safety issues, are just used to lend a veneer of legitimacy to religious fundamentalists’ desire to suppress everything they find offensive. They know that the vast majority of drinkers in Malaysia are responsible, but they ignore the statistics and turn a blind eye to the thousands of annual road traffic deaths caused by motorcyclists, dangerous driving, and poor safety standards that burden our under-funded health care system and leave families poor with the loss of breadwinners.

Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin made a “joke” at a Perikatan Nasional convention Tuesday that “it may be a good thing” if pubs and nightclubs “don’t open at all” after the end of the Recovery Movement Control Order (RMCO). If it was indeed a joke at a predominantly Malay-Muslim gathering, it was extremely inappropriate for the prime minister to jest at hardworking Malaysians who may end up jobless, since nightspots would have been closed for at least nine months since March until the end of the year when the RMCO is scheduled to end.

The Federation of Malaysian Entertainment Industry made a good point that if physical distancing was the reason to continue keeping nightspots closed, then political, religious, and public gatherings should be banned as well. Bars and nightclubs in various countries have employed safe distancing strategies, like plastic barriers separating DJs and guests at a nightclub in Bangkok, Thailand; protective screens at pubs in England; or having patrons dance from physically distanced chairs at a Dutch nightclub in the Netherlands.

Religious conservatives say that people can just drink at home. That’s not the point. The point is that Malaysians have the constitutional right to personal liberty – which means the freedom to live our lives as we see fit as long we don’t harm other people. That includes the freedom to socialise outside with friends with a drink or two.

We have the right to consume alcohol in public – in pubs, bars, or nightclubs – just like how people have the right to drink teh tarik with friends at mamak restaurants.

We will not hide our way of life by drinking in private at home because Malaysia is a diverse country with people of varying lifestyles.

People who choose not to drink – for whatever reason, be it religious or otherwise – can just avoid patronising pubs, rather than force everyone else to follow their way of life.

I have friends, including Muslims and Christians, who drink. I also know some Christians who do not consume alcohol. A friend of mine doesn’t imbibe because she’s allergic to alcohol. Claiming that all religions prohibit alcohol consumption is a poor excuse for wanting to close down pubs or ban alcohol, as different people interpret their faith differently. Again, it’s a personal choice that should not be taken away by the State.

If it’s a matter of health, there are various studies on the risks and benefits of drinking moderately. People have the right to make decisions over their personal health, whether it’s drinking a glass of wine at a social outing, or eating fast food without exercising until you die of a heart attack. Policymakers simply need to promote health education so that people make healthier choices, rather than ban everything that affects our health. Nearly one in five Malaysian adults is diabetic, but no one is asking for a ban on mamak restaurants or sugary drinks. Malaysia still has problems with illegal narcotics even though we have among the harshest drug laws in the world.

Closing down the nightspot and entertainment industry in Malaysia will lead to unemployment, at a time of historically high job losses during a pandemic, and hurt tax revenue. The government collected RM3.6 billion in tax revenue from alcohol sales between May 2018 and September 2019. That money funds everything, from welfare programmes to religious departments.

Civil liberties are not just about fighting for the “good” things, like the right to practice religion. It’s also about protecting our freedom to make personal choices that may seem “bad” to other people. If we do not speak up for our constitutional right to personal liberty over the latter, religious fundamentalists will slowly chip away at our freedoms until they take away even the “good” things.

Boo Su-Lyn is CodeBlue editor-in-chief. She is a libertarian, or classical liberal, who believes in minimal state intervention in the economy and socio-political issues.