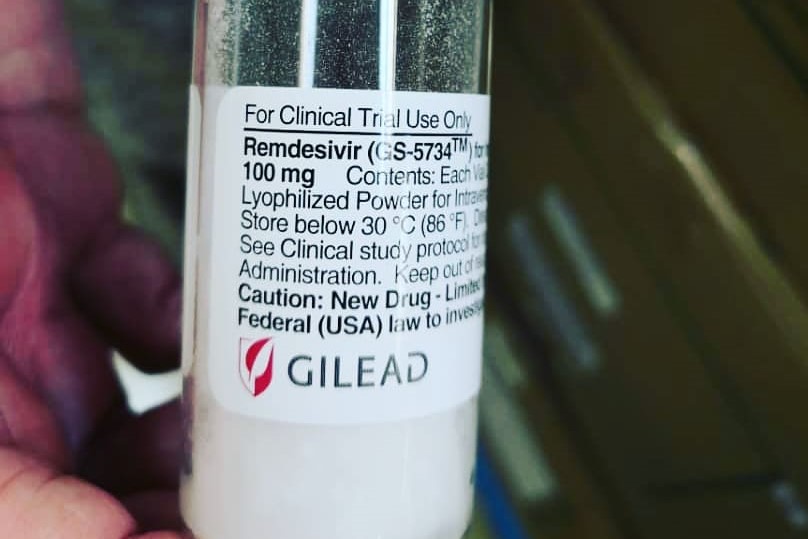

Gilead Sciences recently excluded Malaysia, as well as Singapore and Brunei, from obtaining generic versions of remdesivir — the frontrunner potential treatment for Covid-19 – in recent deals the US pharmaceutical giant struck with five generic companies in India and Pakistan.

Gilead’s exclusion of Malaysia from these non-exclusive voluntary licencing agreements — which allow those generic companies to manufacture and distribute the antiviral drug to 127 poor and some middle-income countries — has angered federal lawmakers, who pointed out that Malaysians were risking their lives participating in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) global clinical trial on remdesivir and other potential Covid-19 medicines.

The Ministry of Health (MOH) declared that Malaysia would use “other means” of accessing remdesivir if the experimental medicine was proven effective for Covid-19. But Health director-general Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah stopped short of saying if Malaysia would resort to compulsory licencing to obtain cheaper generic versions of remdesivir without patent owner Gilead’s consent, which is what we previously did in 2017 with sofosbuvir (brand name Sovaldi) — a breakthrough drug, also by Gilead, that cures Hepatitis C.

The Malaysian Health Coalition – a group of health professional societies – has urged the pharmaceutical industry to publish the criteria for inclusion in the voluntary licencing agreements for remdesivir, arguing that Malaysia, which already underspent on health even before the Covid-19 pandemic, may not be able to spend much. A lecturer in pharmacy similarly argued there was no reason for remdesivir to be “highly priced”, saying that even a price tag of US$390 (RM1,700) for the treatment might be too expensive for many Malaysians.

Two Members of Parliament – Klang MP Charles Santiago and Bandar Kuching MP Dr Kelvin Yii — from centre-left party DAP argued that although Malaysia is classified by the World Bank as an upper middle-income country, the gap between the rich and the poor is wide. Thus, Malaysians shouldn’t be left out of any treatment on the basis of their socio-economic status. Charles told pharmaceutical companies not to profit during a pandemic and said Covid-19 treatment should be considered a “public good”.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), a US nonprofit that analyses drug pricing and is said to often find drugs to be overpriced, justified a cost-effective price of up to US$4,500 (RM19,636) per treatment course for remdesivir, assuming that the medicine has some mortality benefit. If remdesivir only shortens hospital stays, then the value-based price drops to US$390 (RM1,700). A US clinical trial found that remdesivir cut recovery time for Covid-19 by four days and suggested, but did not prove, that the drug could prevent deaths.

ICER also gave a cost-recovery pricing model for remdesivir at about US$10 (RM44) for a 10-day course, setting zero costs of research and development based on the argument that remdesivir was previously developed as a part of a suite of treatments for Hepatitis C, and that Gilead had likely recouped such sunk costs in the successful launch of its other Hepatitis C drugs. The California-based biotech company previously courted controversy in 2015 for charging US$84,000 (RM360,000) for a full course of treatment of sofosbuvir.

Gilead should have included Malaysia in its voluntary licencing agreements for remdesivir, just like how it previously announced on August 24, 2017, the expansion of its sofosbuvir generic licencing agreements to include Malaysia, Thailand, Ukraine, and Belarus.

Unfortunately, instead of taking up Gilead’s offer of lower-cost versions of the Hepatitis C drug, the then-Barisan Nasional (BN) administration used a compulsory licence to enable an Egyptian company, Pharco Corp, to manufacture and export generic versions of sofosbuvir to Malaysia without Gilead’s consent.

The price of sofosbuvir dropped to about US$300 (RM1,200) for a full course of treatment of the generic version from US$11,000 (RM45,000) for the original drug, according to then-Deputy Health Minister Dr Lee Boon Chye from the Pakatan Harapan (PH) administration.

I do not believe that compulsory licencing is the answer to the remdesivir problem. First of all, a political scientist at the London School of Economics, as quoted by STAT, noted that if remdesivir is as difficult to produce as Gilead claims, then compulsory licences won’t likely achieve much.

Secondly, compulsory licencing won’t necessarily guarantee widespread access of remdesivir to Covid-19 patients in Malaysia. We can look at our experience with sofosbuvir. By taking such a drastic step that damaged Malaysia’s intellectual property reputation, we would have expected to cure the majority of an estimated 400,000 to 500,000 people in Malaysia with Hepatitis C.

Instead, an MOH hepatology official reportedly said last November – just before the novel coronavirus pandemic hit the world this year – that only 4,500 Hepatitis C patients received sofosbuvir, just 0.9 per cent of an estimated half a million Malaysians with the liver infection. Why was the treatment rate so low despite slashing the drug price by 37.5 times? Was it because of irregular supply from the manufacturer, or other issues?

Would more Hepatitis C patients have been treated if Malaysia had agreed with Gilead’s voluntary licencing terms? An Imperial College London study, funded by Unitaid and Doctors Without Borders (MSF), found a link between voluntary licencing for Hepatitis C medication and increased access to treatment in low- and middle-income countries, saying these agreements could contribute annually to an additional 54 to 69 people receiving Hepatitis C treatment per 1,000 individuals diagnosed with the viral infection.

Malaysia’s renewal of the compulsory licencing agreement for sofosbuvir is up this year. It’s unclear if the Perikatan Nasional (PN) government — which includes BN that signed the agreement in the first place – will renew it, or let it lapse in exchange for remdesivir for Covid-19 patients that currently number at 1,323 people (the number of those who require hospitalisation may actually be lower because Malaysia places everyone who tests positive in hospital, regardless if they need treatment or not).

The argument that Malaysia doesn’t spend enough on health care and that Malaysians shouldn’t be denied access to treatment based on their income, while valid, erroneously presumes that all residents in Malaysia can only afford to pay one single price for remdesivir. However, I don’t believe that the Malaysian government should necessarily give a 99 per cent subsidy and charge Malaysians only RM1 for any medicine that is proven to treat or cure Covid-19.

Health care shouldn’t be treated like welfare – there is a cost to everything; the goal is simply to ensure that as many people as possible can pay the price.

If even the bottom 40 per cent (B40) can buy a TV or a cheap mobile phone for a few hundred ringgit, why can’t they purchase medicine for that price? As for Malaysians who buy imported cars or don’t think twice about dropping RM50 for brunch, they can certainly afford to pay RM2,000 for remdesivir. And for the rich who make RM20,000 a month, a RM4,000 drug price may not severely dent their earnings. The Malaysian government shouldn’t underestimate people’s willingness to pay for medicine.

Charging a grossly minimum sum like RM1 for health care leads to wastage because people generally don’t appreciate free things. Even a packet of no-frills nasi lemak costs more than RM1. Any medicine that can cure Covid-19 – one of the biggest disasters to hit the human race – must surely be more expensive than a meal of rice, ikan bilis, and sambal thrown together.

So far, no studies have been published on wastage in government health facilities, though there have been anecdotal reports from doctors and pharmacists about drugs like insulin left gathering dust in people’s homes. MOH reportedly disposed almost RM2 million worth of expired medicines in two years from 2014 to 2015.

If Malaysia does eventually have tens of thousands of people requiring hospitalisation for Covid-19, the government could consider a co-payment model like in South Korea and share costs of remdesivir with individuals, depending on their income levels. The bottom 10 per cent, or hardcore poor, can receive perhaps 99 per cent subsidy from the government, with the percentage of cost-sharing going up commensurately with one’s income. The government could also work with insurance companies to reduce out-of-pocket payments. Malaysia should do bulk purchasing for any Covid-19 drug, instead of MOH, university hospitals, and private hospitals all buying it separately.

So how much should remdesivir be priced in Malaysia? A US law school professor specialising in intellectual property told STAT that US$1,000 (RM4,364) was the sweet spot, with some profit to incentivise other pharmaceutical companies to develop better drugs, but not too lucrative that it discourages Gilead from further investigating the benefits of remdesivir that has yet to be proven to prevent death.

Business Insider quoted a biotech analyst who estimated that Gilead could make US$1 billion (RM4.36 billion) on remdesivir by the end of the year if the drug maker sells one million treatment courses in the US and internationally based on a US$1,000 placeholder price tag, which he described as “pretty reasonable” in modern drug pricing. Gilead, which has yet to set a price for remdesivir, reportedly said in a quarterly financial filing that its investment in remdesivir this year could reach up to US$1 billion or more, much of it for boosting manufacturing capacity.

Arguments that pharmaceutical companies shouldn’t make profit during a pandemic are usually driven by emotion. How much profit is considered “reasonable”? 10 per cent? 30 per cent? 60 per cent? What’s the rationale for these margins? If companies don’t make profit, why should they (i.e. people running the companies) be motivated to take risks and spend lots of money, talent, and other resources to create the best possible medicines?

In a capitalist system, money is the best motivator. While some may find this unpalatable for lifesaving products like medicines, the fact remains that producing treatment takes work, just like any other human endeavour, and people cannot work for free.

Talent must be rewarded so that we are incentivised to attain even greater achievements; otherwise, we remain stuck in mediocrity.

Until the centre left find a coherent alternative to capitalism, without simply railing against billionaires, capitalism remains, so far, the most adequate system of filling basic needs while encouraging innovation and improvement of the human condition.

The market, not the State, is the best determinant of prices, including in health care. In the case of Covid-19, bulk purchasing for an effective treatment or vaccine will likely reduce prices. Allowing drug makers to make profit could also incentivise competing companies to produce even better medicines for Covid-19, with competition driving prices down. This may widen access to treatment, rather than forcing an arbitrary price for a “public good” that could inadvertently remove access altogether, if no therapies are made at all.

The value of a cure for Covid-19 – which has killed nearly 350,000 people globally, devastated economies, and brought the world to a standstill – shouldn’t be purely derived from its price tag.

The price of saving lives, resuming economic activity, and being able to touch our loved ones is, frankly, incalculable. So, simply pushing for a low or affordable price for drugs or vaccines that can effectively treat or prevent Covid-19 undermines the real value of returning to the Old Normal of socialisation. Put another way — how much are we willing to pay, or give up, to go back to normal?

The last point I wish to make is that Malaysia must decide if it wants to remain a developing country and ask to be treated like poorer economies such as Bangladesh, or if it wants to be a high-income developed nation with a knowledgeable population.

We can’t ask for dirt-cheap drug prices and, at the same time, demand respect as a regional leader. Intellectual property is crucial in developing a knowledge economy. We should aim to have top scientists in the life sciences who can one day, hopefully sooner rather than later, create breakthrough treatments. Wouldn’t we want to protect their intellectual property rights?

Boo Su-Lyn is CodeBlue editor-in-chief. She is a libertarian, or classical liberal, who believes in minimal state intervention in the economy and socio-political issues.