Each year on April 17, the global haemophilia community celebrate World Haemophilia Day to raise awareness and increase support for people with haemophilia and other inherited bleeding disorders.

With so much attention and resources poured into the Covid-19 public health emergency, it is easy to forget that thousands of people are living every day with conditions and illnesses which require constant treatment and cannot afford deferment or interruption in their therapies.

For more than 1000 individuals living with haemophilia registered in Malaysia, measures such as the restrictions under the Movement Control Order are cause for concern and anxiety, particularly as they affect the ability to seek medical treatment which may require crossing state borders.

Haemophilia is a genetic disorder where the blood is unable to clot properly, and it takes longer than normal for bleeding to stop. Depending on the severity of the condition, it can lead to life-threatening, bleeding episodes caused by innocuous events such as a bump or a cut. It can even go undetected for years until a routine medical procedure causes uncontrolled bleeding.

In order for blood to clot, it requires blood platelets along with proteins called clotting factors. A person with haemophilia has low levels of one of two clotting factors, factor VIII or factor IX. More than half of those affected have severe haemophilia, where their factor levels are less than 1%.

There are two main types: haemophilia A and B. In A, there is a deficiency of factor VIII and in haemophilia B, there is a lack of factor IX . Haemophilia A affects around 1 in 5,000 male births, while haemophilia B is less common and only affects around 1 in 25,000 males.

A chronic condition, having haemophilia doesn’t mean that a person bleeds faster. They bleed for longer periods of time. It can be fatal.

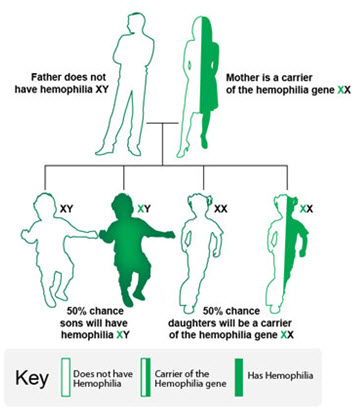

Haemophilia is known as a sex-linked condition because the genes which govern factors VIII and IX are situated on the female (X) chromosome. A boy born to a mother who has the gene has a 50% chance of having haemophilia. Her daughters have a 50% chance of being carriers, which may in turn affect their sons.

As a result, though it is possible for girls and women to have the disorder which will cause complications during menstruation and childbirth, haemophilia is more common in boys and men.

There is no cure for this condition.

A century ago, the average life expectancy of a person living with severe haemophilia was just 16 years, due to the lack of treatment options. In 1960, this was about 20 years. Most would not live beyond late thirties. They died from either external or internal bleeding.

However, treatment became available and progressed significantly over the past decade. Initially, patients had to rely on regular blood transfusions after a bleeding episode which caused them to be vulnerable to chronic joint damage and communicable diseases.

Today, even severe haemophilia can be treated. With options ranging from primary prophylaxis treatment with regular intravenous injections of the missing clotting factor, to on-demand treatment, people living with the chronic condition can live active, healthy and productive lives. Bleeds can be prevented and controlled. There is no reason for them to not have the same access to opportunities as anyone else.

However, managing the condition can still be difficult. Those living with the condition or caregivers may face medical, psychological, social and financial challenges. A strong support network is vital as part of comprehensive care.

As a result of the Malaysian government’s commitment to providing quality treatment and care for those living with haemophilia, people with the chronic condition are living much longer.

When a person has haemophilia, he spends a lifetime of being told what he cannot do. Hopefully, with the public’s support and increased availability of newer treatment, he can start looking forward to seeing a future with no limits to what can be achieved.

Azrul Mohd Khalib is CEO of the Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.