KUALA LUMPUR, Dec 20 — A doctors’ survey has alleged poor conditions of government health facilities across Malaysia that face regular electricity and water supply interruptions among other infrastructure problems.

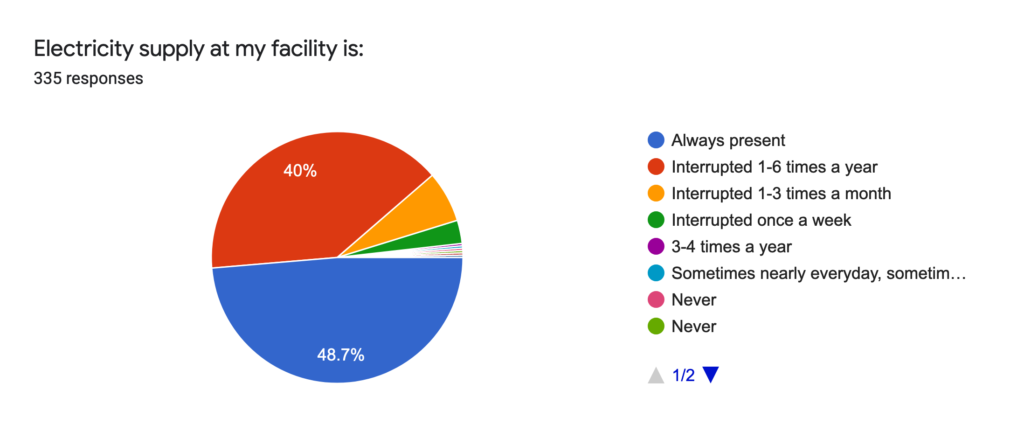

According to the survey conducted from June to November among 337 respondents from government hospitals and clinics in Doctors’ Only Bulletin Boards, a Facebook group of Malaysian doctors, over half of respondents (51.3 per cent) reported electricity supply interruptions at their medical facility at least once a year, with 10 per cent complaining of power cuts up to once a month.

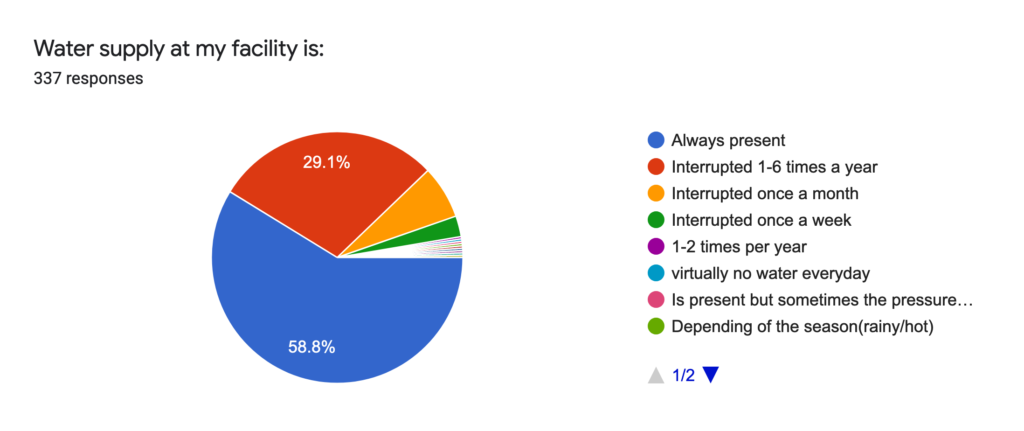

About four out of 10 respondents (41.2 per cent) said their government medical facility faced water supply interruptions at least once annually, with about 10 per cent claiming monthly water cuts.

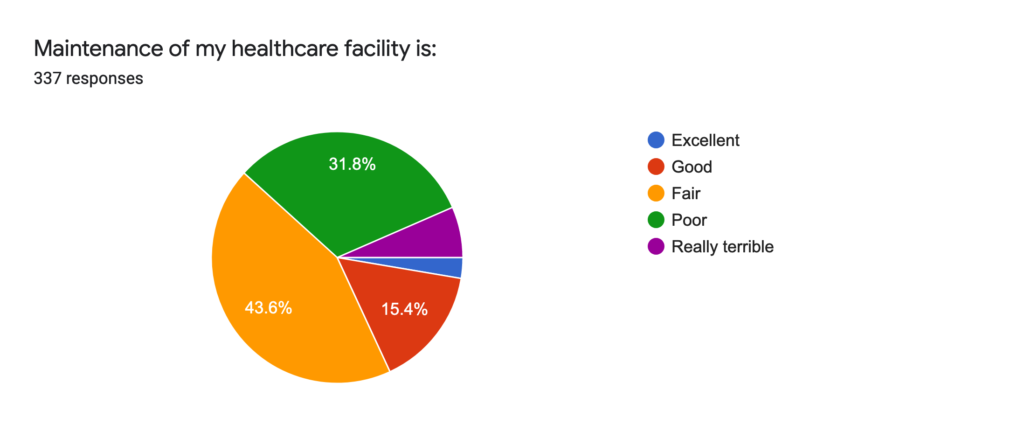

About 38 per cent of doctors rated the overall maintenance of their public health facility to be “poor” or “really terrible”. About 44 per cent gave a “fair” rating. Only about 18 per cent rated the conditions of their facility as “good” or “excellent”.

The government hospitals with reported power and water cuts up to six times a year included Sultanah Aminah Johor Bahru Hospital and Segamat Hospital in Johor, as well as Raja Permaisuri Bainun Hospital in Ipoh, Perak.

Other public health facilities reportedly experiencing water and electricity supply disruptions between one and six times annually were based in Sarawak — Bintulu Hospital, Sibu Hospital, and Balai Ringin government health clinic in Serian — as well as Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Queen Elizabeth II Hospital, Keningau Hospital, and Pitas Hospital in Sabah.

A respondent complained that Kepala Batas Hospital in Penang suffered water cuts every month, while electricity supply was disrupted up to six times a year.

Another claimed that Raja Perempuan Zainab II Hospital in Kota Baru, Kelantan, had “virtually no water everyday”, besides suffering power cuts between one and six times annually.

Duchess of Kent Hospital in Sandakan, Sabah, reportedly experienced water cuts every week and electricity supply disruptions up to six times a year, or more frequently. Kota Belud Hospital in the state also allegedly faced monthly water cuts and weekly electricity supply disruptions. The Membakut government health clinic in Beaufort reportedly faced weekly water cuts, while power cuts occurred up to six times a year.

Sri Aman Hospital in Sarawak reportedly faced up to monthly water cuts and electricity supply disruptions up to six times annually.

A majority, or 60 per cent, of the problems cited in public health facilities were old and failing equipment such as operating equipment or anaesthetic machines, as well as infrastructure issues like cracked walls, broken lights, or collapsing ceilings.

A whopping 80 per cent of doctors said their issues were still not resolved even after two years of filing complaints. Only 7.5 per cent of respondents said complaints were resolved within a month.

Survey author Dr Timothy Cheng said a medical officer (trainee specialist) from a Selangor tertiary hospital told him that the operating theatre in his facility has been malfunctioning for a year due to leaky ceilings and humidity issues.

The issues, he said, were resolved after renovation, but certain major equipment were damaged, causing a delay in operations and patients to be transferred to other centres.

“Health care facility issues have been plaguing the Ministry of Health for a long time and this is only the tip of the iceberg,” Dr Cheng wrote.

“Audits that are held ever so frequently are merely a show and a waste of money.”

Dr Timothy Cheng

“How often have we received instructions to ‘wear white coats’, ‘fill up the wards” before an audit? The hospital is suddenly a flurry of paperwork and files, just to fulfill the requirements of certain certifications. Walls and walkways are suddenly painted and new signboards even installed,” he said.

“From the results of the survey, it is evident that we need a better evaluation and assessment system of our health care facility and infrastructure as the current methods are ineffective. An open channel for those on the ground to file direct complaints rather than go through a bureaucratic process should be started to enable better reporting of facility failure.”

Out of the 337 respondents working in government clinics and hospitals, 73.5 per cent were medical officers and 19 per cent were specialists, while the rest were house officers and staff nurses or paramedics.

Most respondents in the survey didn’t name the public health facility they were employed in. Some respondents could also be working at the same government centre.