There’s much to be proud of when it comes to Malaysia. The previous three decades in particular have brought about development in leaps and bounds which have translated to a better and much improved quality of life for us compared to that of our parents and grandparents.

Consider, for example, the life expectancy of the average Malaysian. Back in 1970, just several years after the formation of Malaysia, one expected to live up to 64 years. Today, it is 74.7 years, with a male child born in 2016 expected to live up to 72.6 years and a female child up to 77.2 years.

Much of this is due to a health care delivery system on par with that of developed countries which can lay claim to coverage of more than 90% of the population being able to access at least basic services within a 5km radius of their home, while 81% live within 3km of a health facility.

For us, universal health coverage isn’t an aspiration, it’s a reality.

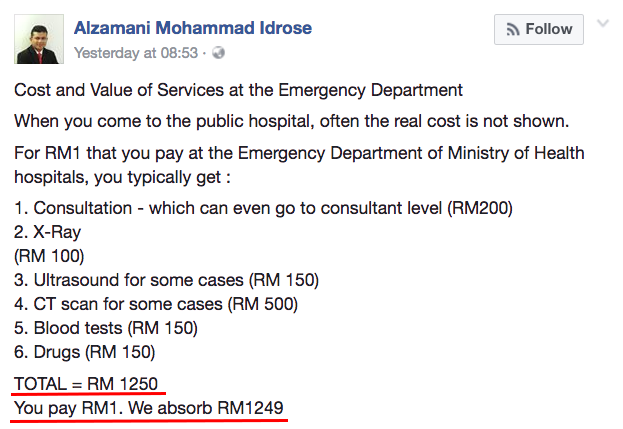

With charges between RM1 and RM5 for outpatient and specialist care respectively, Malaysians are able to access high quality treatment and care at government clinics and hospitals.

At the outpatient level, this could be inclusive of consultation with a doctor, some tests and even a month’s worth of medication. Patients pay a fraction of the costs expected for common surgical procedures such as an appendectomy. In many instances, an appeal can be made for even that to be waived or a further discount to be given.

It is not an exaggeration to say that this health care delivery mechanism comprising both public and private bodies, despite its shortcomings, is the envy of many countries in the Asian region, particularly those still developing their economies.

However, it might be past time for us to take an honest look at the system.

There are essential overhauls and reforms needed to be done to ensure that health care remains accessible, affordable to Malaysians and, most importantly, sustainable for years to come.

One such reform urgently needed is in the area of health care financing.

Let’s face it. Healthcare does not cost RM1. It never has and never will.

Every single patient entering the public system had more than 90% of their actual costs borne by the Government using the public purse.

But this purse isn’t bottomless and demands on it are getting ever bigger.

A direct consequence of having people live longer, an increasing ageing population and more non-communicable diseases is a health burden which gets progressively larger and heavier each year.

Unfortunately, simply increasing expenditure on health care would not solve the problem. It is true that Malaysia currently spends 4.3% of its GDP on health, which is below the average for upper middle-income countries. We could spend more.

It is also true that health spending per capita in Malaysia increased 2.5 times in 17 years, from RM641 in 1997 to RM1,626 in 2014.

The total healthcare expenditure in Malaysia for 2017 was RM52bil with the public-private ratio being 55:45.

The Inland Revenue Board collected RM114bil in 2016. It may sound a lot but consider the fact that only 10% out of 14 million workers nationwide paid income tax that year. The majority didn’t make enough to require them to pay tax.

This is also the same source of funding for everything else in the national budget, such as infrastructure development, welfare, education, defence and sports.

It is easy to point the finger at private clinics and hospitals, the pharmaceutical industry and other actors in the health care sector, and blame them for the escalating cost of medical care.

Hearing the amounts paid in the private health sector in comparison to the charges in public facilities for similar treatment, more than 39% come from out-of-pocket spending with patients and families risking financial trouble, it is understandable for people to get upset and outraged.

But the reality is that there is little difference in actual costs between public and private health care delivery. The impression that treatment in public facilities is cheaper is misleading and creates animosity and hostility towards private service providers.

The current level of subsidisation is increasingly untenable and unsustainable. If we are to ensure and maintain what we have today, urgent reforms are needed.

So what can we do?

The ideal would be for a single-payer, multiple-provider system where public and private institutions would be equally accessible to the patient. This would be the most efficient and cost-effective system.

However, it would also require a massive upheaval and overhaul which could be severely disruptive in the short term. It would also necessitate the setting up of institutional structures and systems which might not currently be in place. However, this should be the long-term goal.

One approach which we can take right now would be to get behind the idea of a national health insurance scheme, an idea currently being seriously considered by the Health Ministry.

Maintaining Malaysia’s current two-tier system would require a multi-payer approach. Imagine being able to make a monthly contribution to a national pool of funds similar to what you already do under Socso.

This would be applicable to all workers and be based on a sliding scale linked to monthly income and age. There would be collective pooling of both funding and risk. People would be able to opt out.

People already with their own insurance should be able to keep it but also be given the choice to also contribute to the national scheme. They would then be able to access both public and private facilities.

Those contributing only to the national scheme would be entitled to access the public health care system.

The above suggestions do not change much of the status quo regarding access but it does widen the funding base.

It would begin to address the issue by co-sharing the burden and responsibility of financing the health care system. It has the potential to stabilise public subsidisation and allow space for cost-containment while maintaining access and quality to essential services.

Azrul Mohd Khalib is Chief Executive Officer of the Galen Centre for Health & Social Policy

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.