KUALA LUMPUR, May 27 — A general practitioner (GP) at a corporate clinic has defended GP clinics charging more than pharmacies for medicines, citing delayed payments from corporate clients and managed care organisations (MCOs) or third-party administrators (TPAs).

The primary care doctor also cited GPs’ low consultation fees that have stagnated at RM10 to RM35 for more than three decades and rising operating costs for clinics over the years.

Dr Chong Khah Shin, who operates Klinik Genting Sdn Bhd on the eighth floor of Wisma Genting on Jalan Sultan Ismail here, said his clinic applies a markup of 25 to 30 per cent on medicines, in line with the recommended selling price (RSP) set by pharmaceutical companies.

“We follow pharmaceutical companies’ recommended selling price. Usually, they recommend a markup of about 25 to 30 per cent. We follow the recommended selling price,” Dr Chong told CodeBlue during a clinic visit on May 16.

About 80 per cent of the medicines stocked at Klinik Genting are branded.

The clinic primarily serves corporate clients — largely Genting Group employees and patients covered under insurance or corporate health panels such as AIA, Allianz, and Etiqa, as well as MCOs or third-party administrators (TPAs). Walk-in patients are rare, as lobby security limits public access.

Dr Chong said delayed payments from companies and MCOs are common and create a significant administrative burden.

“A lot of times, when you run a corporate clinic, a lot of companies don’t pay us on time. Not like cash patients. You treat them, they pay cash, and finish. We have to keep chasing, chasing, and chasing (companies and MCOs). We’re always following up, and then they’ll say, ‘Oh, this invoice is missing,’ so we have to redo it and print it again. It’s a lot of work and it takes time,” he said.

“On average, it takes about two to three months. We also have delays that are one to two years. So, how do GPs cover all of this? Medicine.”

Dr Chong also pointed to other cost pressures. He charges RM15 per consultation — well below the RM35 cap set under the Private Healthcare Facilities and Services Act 1998, a rate unchanged for over 30 years — despite higher overheads than typical neighbourhood clinics.

Klinik Genting employs six to eight staff, including an accountant and a pharmacist. The clinic has two consultation rooms, multiple treatment and staff rooms, and a front area with separate registration and dispensing counters. By comparison, many GP clinics operate with two to three staff and occupy smaller premises, such as shoplots or residential units.

“Some companies, if you go to the clinic a few times, they’ll call and ask why the patient is coming so many times,” Dr Chong said, referring to efforts by employers and MCOs to curb clinic visits post-Covid.

A previous check by CodeBlue found prices for medicines such as Zyrtec, a branded antihistamine by GlaxoSmithKline, and Dyna Charcoal tablets to be roughly 40 per cent higher at GP clinics than at nearby pharmacies or on online platforms.

A Berita Harian report also found that private clinics charged between 23 and 75 per cent more for common and chronic medications than community pharmacies.

When asked about the price difference, Dr Chong said pharmacies often sell medicine “almost at cost” or “RM1 cheaper”, but rely on pushing supplements and membership programmes to make up the margin.

“If you talk about prescription medicine, how do you fight with them? We cannot fight with them. Just imagine, you buy a medication for RM100, some pharmacies sell it for RM99. But the moment you enter, the staff will start pushing supplements, asking you to sign up for membership lah, all of that. Clinics don’t do that.”

Patients Rarely Engage With Drug Price List

During CodeBlue’s three-hour visit to Klinik Genting last May 16, most patients appeared to be regulars collecting prescribed medications without undergoing consultation or making payments. Billing was handled by their employers or insurers.

Only one patient — a woman who accompanied her domestic worker for an injection — appeared to pay in cash. She was also the only one who flipped through the clinic’s price list.

Roughly nine patients visited the clinic that Friday, mostly working-age and middle-aged adults. About half came solely to collect previously prescribed medications — typically over-the-counter items or supplements — and completed their visits within five minutes without seeing the doctor.

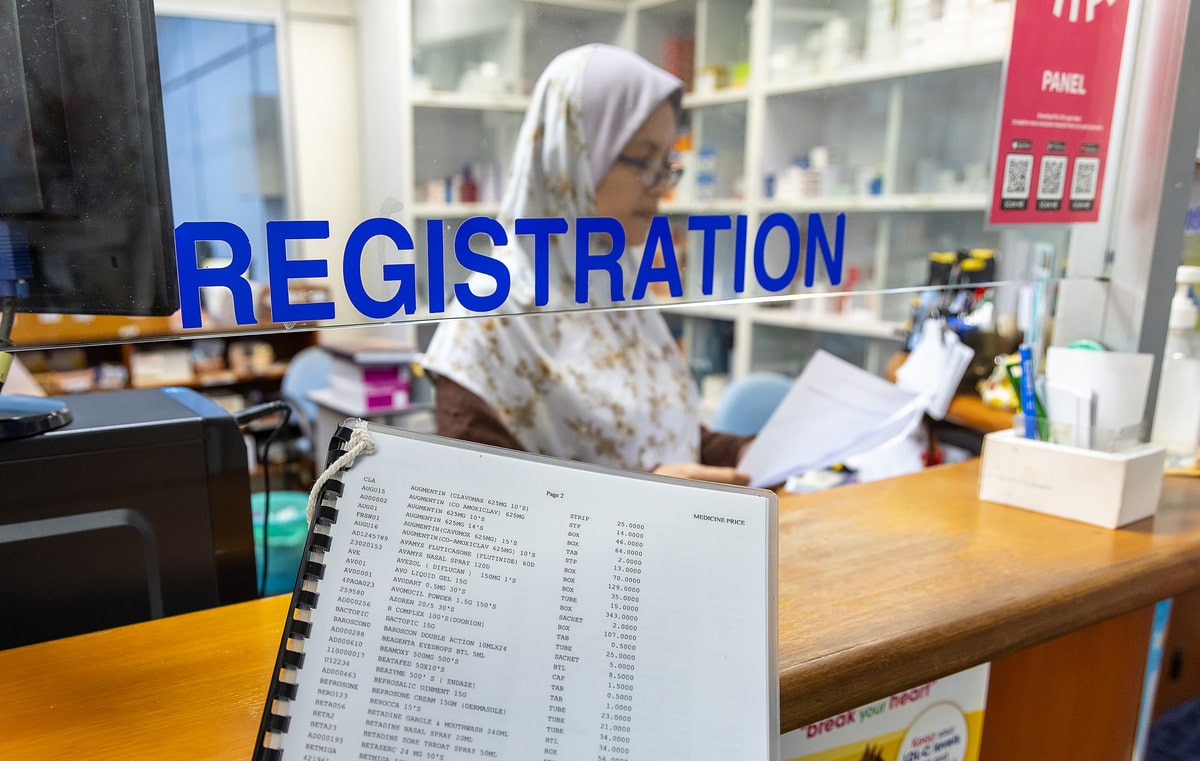

Klinik Genting displays its medication price list at the registration counter. The list, laminated and bound in a 26-page A4 flip-through format, resembles a menu. Despite its visibility, few patients engaged with it.

“Patients are more interested in the medical and supplement brochures (across the room) than the price list,” Dr Chong said.

Compiled by the clinic’s pharmacist over two weeks, the list includes 1,295 items — roughly 51 items per page — arranged alphabetically by brand name. Items no longer in stock are manually marked with an ‘X’.

The list was compiled in a rush to meet the May 1 enforcement date for the mandatory price display ruling. It will soon be updated again to comply with detailed guidelines issued by the Ministry of Health (MOH). The regulation, enforced by the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry (KPDN), is currently in a three-month educational phase.

Klinik Genting’s price list covers a wide range of items, from common medicines like Panadol to skincare products such as Cetaphil cleansers, as well as gloves, surgical masks, orthopaedic supports, creams (e.g. Candazole), lozenges (e.g. Difflam), Covid-19 test kits, and supplements like Blackmores and Pharmaton.

Klinik Genting stocks about 80 per cent branded medicines, with limited generic options. Prices vary significantly — from as low as 50 sen per tablet for generic metformin 500mg (for diabetes), to RM1,442 for Profortil (180s, a male fertility supplement), and RM2,560 for Neuroaid (180s, a supplement for stroke recovery and cognitive support).

Patients who stopped only at the dispensing counter likely missed the price list, which was positioned at the registration area. Those who did approach the counter typically glanced at the first page but did not flip through the list, except for the cash-paying patient.

One sales representative who visited the clinic took photos of the price list to compare pricing for their company’s products — the only other person observed showing interest in the display.

Only a few patients sought consultations that day, with most asking if Dr Chong was available. With strong doctor-patient trust and few paying out of pocket, there appeared to be little reason to question the cost of medications, even when prices are significantly higher than those at local pharmacies.

For now, Dr Chong says complaints are rare — likely because most patients never see the bill.