We refer to the recent posters released on the Ministry of Health’s (MOH) social media platforms on the use of diclofenac as a suppository in children with fever. It is obvious that the creators of these infographics have not verified the content with their paediatrician colleagues in MOH.

This incident is not unlike an earlier report in the New Straits Times on January 4, 2020, that bore the headline “Health Ministry: Stop using NSAIDs to treat children for fever.”

Many of us in the paediatrician fraternity are aghast at this inaccurate and outdated information for the treatment of fever, which is causing unnecessary fear and panic among the parents of our little clients.

Cracking The Science

A few colleagues have shared an article from the National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Authority (NPRA), which was supposedly the basis for these two posters.

The article which was published in April 2023 and titled “Off-Label Use of Diclofenac Suppositories to Treat Fever in Children: Potential Risk of ‘Acute Necrotising Encephalopathy of Childhood’ (ANEC)” stated that there were “two reports of suspected ANEC potentially related to the off-label use of diclofenac suppository for treating fever in children”.

It is pertinent to ask for the specifics of the two cases, in particular if influenza was diagnosed, or there were positive isolates for human herpesvirus (HHV)-6/7, rotavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, mycoplasma or E coli and salmonella (Haemolytic Ureamic Syndrome), or whether ANEC was due to other causes such as metabolic disorders, excitotoxicity, and causative agents of cytokine storm.

This is because the articles referenced by the authors were very specific on the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), e.g. diclofenac sodium and mefenamic acid, which was shown in several cases in Japan to be associated with a significant increase in the mortality rate of influenza encephalopathy.

The researchers in Japan hypothesised that the NSAIDs triggered influenza encephalopathy by either increasing the risk of thrombosis or vascular endothelial injury. (see graph below)

As most cases of ANEC are from Japan, with very few reports outside the land of the rising sun, there have been no studies to verify the association of NSAIDS with the poor outcome of influenza encephalopathy.

Seven out of the nine cases in the report from Turkey were influenza ANEC, but without mention of use of NSAIDs. The ANEC in three brothers of consanguineous parents is in a familial form, though they have not been linked to a mutation in the coding region of RANBP2 (RAN-binding protein 2).

Closer to home, the NPRA article quoted a case report from Universiti Putra Malaysia, whereby a post-mortem of the case was found to be negative for influenza A and influenza B virus, herpes simplex virus, coxsackie virus A, B and 16, enterovirus 71 and 70, echovirus and poliovirus. Gram stain and Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture did not reveal any organism.

Two other cases from Hospital Tuanku Ja’afar, Seremban, found the patient to be positive for Respiratory Syncitial Virus (RSV) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae serology (IgM titre 1:640).

It would be justified to express caution in the use of NSAIDs in influenza with the solitary report from Japan, but to extrapolate it to all forms of fever, irrespective of the cause of fever (elakkan pengunaan supositori diclofenac pada kanak-kanak yang mengalami demam panas) is not based on sound clinical evidence.

To suggest that it might actually increase the risk of febrile convulsion may actually be far-fetched. The febrile child who is running a fever of 39 to 40°C has a 3 per cent risk of developing a seizure. The fever as a cause of the seizure is more likely to be mitigated by diclofenac than by paracetamol, due to the greater anti-pyretic effect of rectal diclofenac.

A study published in the Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal states that rectal diclofenac is a suitable choice for children’s fever treatment, especially in those patients with poor or critical conditions, significantly decreasing the rectal temperature as compared with suppository Paracetamol within the first hour.

Regressing To Tepid Sponging

The MOH poster goes on to suggest “Jadi, nak buat apa? Gunakan kaedah sponging”.

Studies have shown that tepid sponging has minimal medium to long-term effects on temperature. Paediatricians have stopped prescribing tepid sponging many years ago, as it does not reduce core body temperature.

Only anti-pyretic drugs can bring down the fever. This practice is aligned with recommendations of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) which states:

- Tepid sponging is not recommended for the treatment of fever.

- Children with fever should not be underdressed or over-wrapped.

Tepid sponging is time-consuming and may cause distress to both the child and parent. It may also cause shivering if the cooling is too much or too quick. and can lead to vasoconstriction and an increase in temperature and metabolism.

The key role of the health care professional is to accurately and promptly diagnose the source of the fever and treat the underlying disease appropriately, which will reduce morbidity and mortality.

Recommendations from every clinical practice guideline agree on prescribing antipyretics only with the aim of relieving the child’s discomfort caused by fever. There is also a consensus on the type of recommended anti-pyretics, which are paracetamol or NSAIDs.

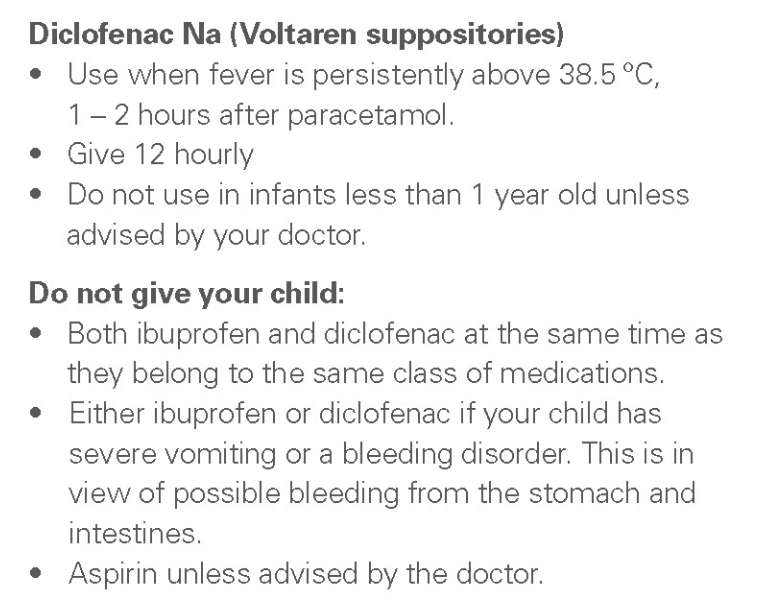

The following two screenshots illustrates the use of medication for fever in children at the Kandang Kerbau Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore.

In conclusion, the issuing of statements or information needs to be meticulously researched and referenced with the relevant experts, as doing so without scientific evidence can cause not only confusion, but also potential harm to patients.

Dr Musa Mohd Nordin, Prof Dr Zulkifli Ismail and Prof Dr Azizi Omar are paediatricians.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.