Since the 1970s, and long before the launch of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Surgical Initiative (2005), Sarawak has been training housemen and medical officers (MOs) to perform caesarean sections, appendicectomies, and many surgical, orthopaedic and obstetric emergencies prior to their postings in district hospitals.

This was in recognition of the serious shortage of specialists, the vastness of the state, and the great difficulty in transportation, costs of referrals, and the delay therefrom.

This is why senior doctors reacted incredulously to the Borneo Post article Marudi Hospital Conducts First Successful Open Appendectomy Surgery and the health director general’s tweet.

The Marudi Hospital Director had, on December 16, 2022, posted on her Facebook page that she and her medical officers had achieved a historical milestone by performing the first open appendicectomy under the WHO’s Global Surgical Initiative. She added that previously, such cases had to be referred to specialists at Miri Hospital.

Doctors who had previously worked in Marudi Hospital were quick to correct the wrong impression this headline gave.

Paediatric oncologist Dr Ong Eng Joe tweeted: “This report is incorrect. This is not the first time appendicectomy was done successfully in Marudi Hospital. It was done by Medical Officers when I was a Medical Officer there in 1998-2000 and even before that”.

To the Borneo Post he emailed: “Please correct this report. Improving surgical capabilities and facilities in the rural hospitals is laudable but rewriting history is not.”

Dr Rahman Gul wrote: “I worked in Marudi in the early 1990s with Dr Rosy, Dr Rehan (GP Malacca), Dr Thomas Samuel (Perkeso). Operating on ruptured appendices, laparotomies, ectopic pregnancies, perforated gastric ulcers, lacerated livers, hernias, caesareans, instrumental deliveries were, but a daily, usual occurrence.

“Others before me, Dr Kamalak Kannan Thangavelu (MOH Baram), Dr Faizul (DMO Miri), Dr Toh and God knows how many more before us, did the same and maybe even much more without batting an eyelid.

“Why did we undertake such tasks? Two reasons: logistics, and also, failure was not an option.

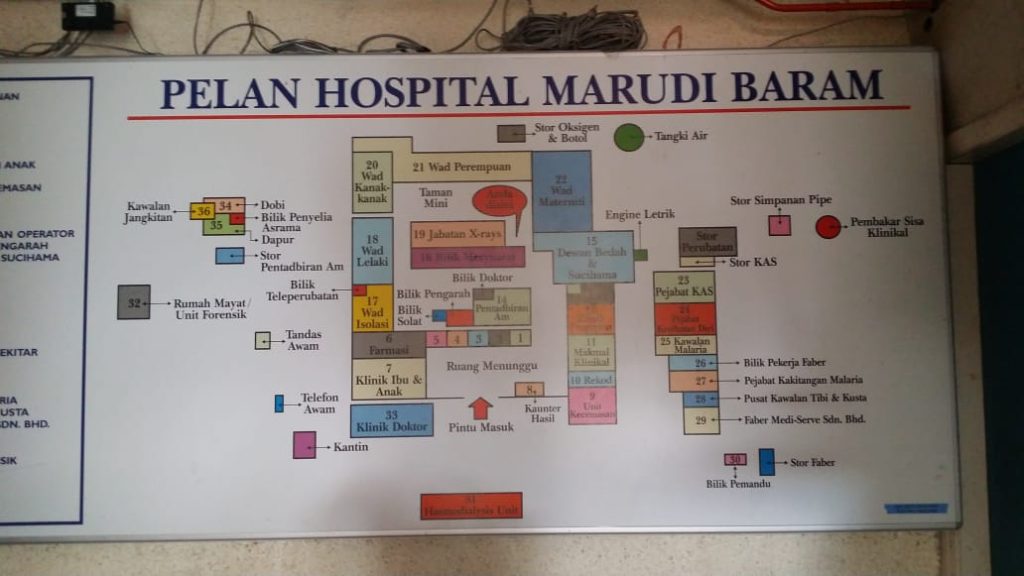

“The Marudi Hospital had no roads linking it to Miri Divisional Hospital. Marudi was accessible only by river up to 330 pm. Boat services were not available when there was no sunlight as the Baram River was full of loose logs.

“The other option was emergency helicopters and flights, again only available before 530 pm. Night flights out of Marudi were not available as the Bell helicopters (used for Medevac and Flying Doctor Service) were not suitable or accredited to fly using instruments at night.

“Therefore, doctors stationed in Marudi (and other logistically challenged districts as well) had to have the courage and skill to handle practically any emergency after five pm.

“Here, I would also take the opportunity to state that our Medical Assistants and Jururawat Desa (JD), nurses, at the various Klinik Desas in the Baram did the most amazing jobs that most doctors would, even today, refer to a higher centre.

“Our anaesthetist was a trained medical assistant. Yes, that is right — not doctors because that was how short of doctors we were back then. The nurses would conduct most of the normal deliveries, set up intravenous lines and duly call us when a difficulty presented itself to them.

“The three doctors of the 54-bedded Marudi hospital covered Baram, an area as big as Pahang. We took turns on Flying Doctor Services (FDS) with a team of two JDs and a Medical Assistant. Some stations like Long San, Long Jeeh, Bario, Long Banga were overnight stays.

“I guess one could say that apart from open appendectomies, a lot more was done by many, many decades ago. I am in awe and appreciation of those that served with me and under me (without the fanfare) in the medical services of Sarawak.”

All MOs trained in Sarawak had to be competent to perform appendicectomies, hernias, orthopaedic reductions, and obstetric emergencies before they left for the district where there were no specialists. After six months each of obstetrics and gynaecology and pediatrics as a houseman, I had to complete two months of surgery before my posting to the 60-bedded, (two MOs) Lundu Hospital (July 1977 -78).

This was during the communist insurrection. Lundu/Bau was a “red area” with frequent military skirmishes. The Kuching-Lundu road was largely dirt and quite treacherous, a journey by ambulance taking four to five hours (one to one-and-a-half hours now on the Pan Borneo Highway). We were under daily curfew. After 6.00pm, the ferry would shut down, and absolutely no road travel was allowed.

Whenever MOs travelled out and I was the solo doctor, surgical emergencies were a challenge. Appendicectomies were common as were obstetric emergencies, including caesareans. The Medical Assistant (MA) was the anaesthetist.

A medical staff member was admitted one night with ectopic pregnancy and suspected internal bleeding. She was looking quite pale, so we had to go around the hospital and school searching urgently for B+ blood donors. Unfortunately, they had all gone travelling.

As I was the only one with B+ blood available, I donated my pint while calling Sarawak General Hospital for surgical advice. Thankfully, she stabilised without the need for me, the now slightly anaemic medical officer, to operate on her. We rushed her off to Kuching as soon the curfew was lifted.

A case of impacted hernia started bleeding after the hernia was reduced. I had to open the abdomen to stop the bleeding and do gut resection and anastomosis. So thankful for the experienced MA anaesthetist and operating theatre nurses who were so well trained by our predecessors.

Of course, with the vast improvements in road communication and the availability of specialists in public and private hospitals, many of such cases will now be referred or given the informed option to choose, where, or by whom. This might be why less surgeries are being done in the district hospitals.

Housemen and MOs in Sarawak should still be trained to do such operations, for the occasional emergency where time is of the essence.

The overcrowding in tertiary hospitals, bed shortages, and limitations in operation theatre, radiological, or laboratory services have probably deprived the present generation of doctors of the learning opportunities for real-time, hands-on surgical and obstetric operations. Not enough cases for too many trainees.

Strategically located district hospitals should be upgraded to become satellite training hospitals where resident or visiting specialists (from tertiary hospitals) can perform scheduled surgery and train doctors and paramedics.

First-year housemen or new medical officers can be rotated, so they can be closely supervised and get the coaching needed to help them transition from medical students to good doctors.

The tertiary hospital operating theatres, beds, and staff can be freed up to focus on more serious or specialised cases, training, and research.

There should be enough surgical trainees and specialists now to be rotated to district hospitals to operate on scheduled elective cases. This will help train up the MOs and maintain and update the proficiencies of the district hospital operating theatre staff.

Posting full-time specialists to every district hospital in Sarawak is not the most cost-effective use of a rare and valuable human resource. Under such conditions, specialists run a high risk of quitting. Perhaps assigning one specialist to cover two or three district hospitals is more realistic and sustainable.

The health director general’s mission to revive, re-equip, retrain, and upgrade the surgical capacities of our district hospitals to make access to timely surgery more equitable is to be applauded.

We look forward to the MOH’s leadership with regard to this initiative. The 50 years of Sarawak district hospitals’ operating theatre success are proof that Malaysian MOs and paramedics have done, and are still doing it, in Sarawak, their jobs quietly and well.

Dr Tah Poh Tin is a public health specialist and paediatrician.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.