KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 5 — Clinicians practicing in chronic pain, palliative care, and cancer in Malaysia largely oppose prescribing cannabis to patients without strong evidence on the drug’s safety and effectiveness.

Malaysian Association for the Study of Pain (MASP) president Dr Mary Cardosa said MASP does not support the use of medical cannabis for the relief of pain, either acute or chronic.

“At this point in time, there is not enough evidence from clinical studies on the benefits of cannabinoids for the treatment of pain,” Dr Cardosa, who is also a visiting consultant pain management specialist at Selayang Hospital, told CodeBlue.

“This is based on the findings of extensive reviews of global data by an expert group from the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), a global organisation with more than 5,800 members from 134 countries,” added Dr Cardosa, who is secretary of the IASP.

Cannabinoids are a group of substances found in the Cannabis sativa plant. The main cannabinoids are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive compound in cannabis that makes one high, and cannabidiol (CBD).

Some cannabis plants contain very little THC, which are considered “industrial hemp” under United States law rather than “marijuana” that refers to parts of or products from the cannabis plant that contain substantial amounts of THC. Malaysia’s Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 that bans cannabis, among other narcotics, does not make such a distinction.

Dr Cardosa explained that the IASP, in 2019, set up a task force of international pain experts – including basic scientists, clinicians, and people with lived experience of pain – to review all the research available regarding the use of cannabinoids in the treatment of pain.

“These reviews, which took two years, concluded that there is currently insufficient evidence from high quality research to support the general use of cannabinoids for the treatment of pain. The expert group found that while laboratory research on a wide variety of cannabinoids holds promise for effective pain relief, most have not yet been tested in pain patients.”

“Of greater concern to us is the potential harm that can come about with the widespread use of cannabinoids, which will occur if the use of marijuana for medical purposes is approved.”

While marijuana containing large amounts of THC can be used recreationally, hemp that contains less than 0.3 per cent THC cannot produce a high, no matter the amount smoked.

“Many of the medical conditions that are said to benefit from the use of medical cannabis are chronic conditions, and as such, we need to study both the short-term as well as long-term adverse effects of cannabis,” said Dr Cardosa, who pioneered work in developing pain services in Malaysia, where she established the first multidisciplinary pain clinic in the Ministry of Health in 2000.

Dr Cardosa cited a review published July 2021 in the medical journal, Pain, on Thailand’s experience one year after legalising the use of cannabis for medicinal purposes in 2019, which found 302 cases of adverse events associated with the use of cannabis were reported between January 2018 and May 2019, including seizures, coma, and the need for ventilation.

She also cited another systematic review published July 2021 in Pain of reported harms associated with cannabis that found cannabis exposure is associated with higher risks of psychosis, depression, suicidal ideation, negative neurocognitive effects, respiratory problems, and cardiovascular problems.

“While many of these studies/ reports were in the setting of non-medicinal use, it does indicate the need for caution and concern,” Dr Cardosa said.

“This evidence and safety signals should be also taken into consideration when making a decision about the potential risk-benefit of using cannabinoids to treat chronic pain.”

Dr Cardosa commended Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin for visiting Thailand last month to learn from Thailand’s experience, after the neighbouring country legalised the cultivation and possession of cannabis by removing marijuana from its banned narcotics list in June this year.

“But [we] urge him to also visit the clinicians who have first hand knowledge of the effectiveness of the drug, as well as its adverse effects.”

Dr Cardosa pointed out that researchers who reviewed Thailand’s experience after the Thai government legalised medical cannabis in 2019 recommended that “well-planned strategies, including education for medical professionals and patients, informing public awareness and an adequate quality-controlled supply of standard cannabis-based medicinal products are needed before the implementation (of policies legalising medical cannabis).”

“Does Malaysia have any of the above in place?” she questioned. “Malaysia definitely also needs to learn about what needs to be done before we can allow medical cannabis to be prescribed to the Malaysian public.”

She urged MOH to consult MASP before making a final decision on the use of cannabis for pain management.

“We call on the Ministry of Health to consider ALL the scientific evidence currently available before making an important decision on the use of cannabis for medicinal purposes, a decision which has far reaching implications for clinicians, patients, and the public alike.”

Bernama reported Khairy as saying during his working visit to Thailand that the Malaysian government would take a stand on medical cannabis before the end of the year. The health minister also reportedly said cannabis is increasingly used internationally in palliative care, chronic pain management, insomnia, and cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Cannabis Plugs Unmet Need In Pain Management, Malaysia Must Avoid Opioid Crisis

Dr Maya Nagaratnam, a doctor specialising in anaesthesiology and critical care with Pantai Hospital, held a differing view from MASP, saying that cannabis is a useful alternative to opioids in pain management, amid America’s opioid crisis.

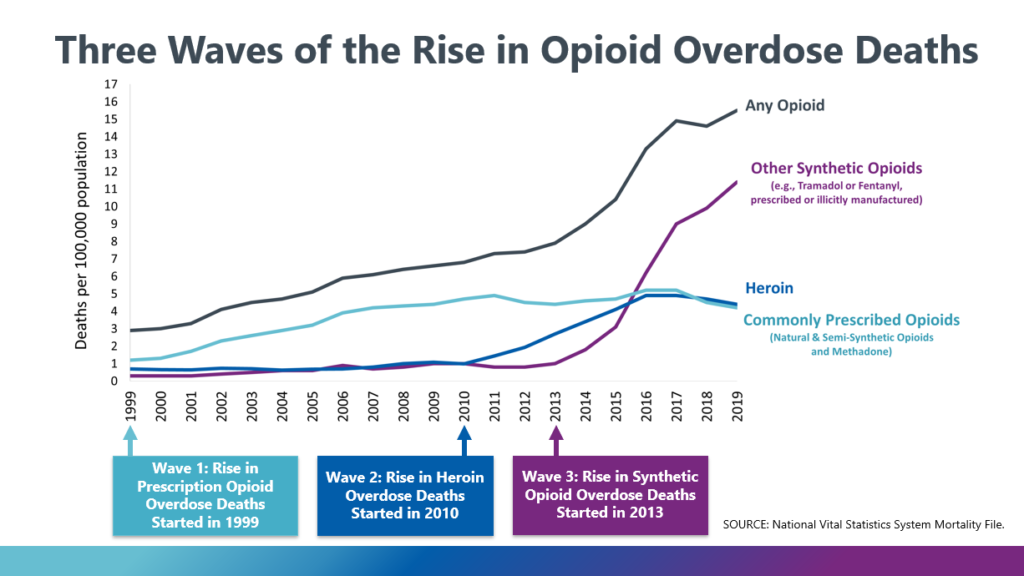

The United States’ opioid crisis began in the mid-1990s when the powerful prescription painkiller OxyContin was promoted by pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma and approved by the United States’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA), leading to three distinct waves of opioid overdose deaths.

NPR reported last March that OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma and members of the Sackler family reached an agreement with nine state attorneys general in the United States to pay a US$6 billion settlement in opioid lawsuits.

Critics have reportedly long accused the Sackler family of aggressively marketing opioids in ways that contributed to soaring rates of addiction and overdoses in America. Drug overdose deaths in the US rose to a record high of over 100,000 people in 2021, according to the US’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). More than 80,000 Americans died last year using opioids, including prescription pain pills and fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 100 times as powerful as morphine.

“Opioid usage currently is tainted and in crisis as we follow the Western trend due to substance abuse issues,” Dr Maya told CodeBlue.

“Cannabis plugs an unmet need in the armamentarium of pain treatment. It has emerged as a useful product in pain management and I think – with proper regulations and named patient prescriptions and under a pain physician overseeing the treatment regime – can be useful.”

Named patient prescription is a method of prescription where the doctor — in certain circumstances — prescribes medication based on the special need of the patient. This method of prescription comes into play when the license for the drug has not been granted because of ongoing clinical trials, discontinuation of the medication, drug shortages, temporary supply problems, clinical trials, and the special needs of the individual patient.

In her practice, Dr Maya stated that she utilises an opioid prescription agreement to better monitor her patients.

Patient contracts, like the one Dr Maya employs, is a method that allows health professionals to monitor their patients’ adherence to treatment plans. This contract or partnership is defined as an “explicit bilateral commitment to a well-defined course of action,” and is widely used in many academic pain management centres in America.

“The problem is – we don’t have widespread methadone available, which is the antidote,” said Dr Maya, in explaining the need to monitor patients on prescription opioids.

More Effective Palliative Medications With Less Side Effects Than Cannabis

A doctor specialising in palliative medicine at a private hospital in the Klang Valley said she does not support the use of medical cannabis in palliative care in general due to the lack of good evidence.

The palliative care physician pointed out that there is “very limited” evidence when it comes to the use of cannabis in symptom management that suggests only “marginal” benefit in very select therapeutic areas, such as chronic pain from cancer and non-cancer related disease, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, HIV/AIDS anorexia and cachexia (wasting syndrome), specific seizure disorders, and spasticity related to multiple sclerosis.

“For symptoms like pain, nausea and vomiting, we have other more effective and reliable medications that have minimal side effects compared to medical cannabis,” the doctor, who requested anonymity due to the “polarising” nature of the issue, told CodeBlue.

She also highlighted, disturbingly, the rise of patients and their family members in Malaysia who ask for medical cannabis not to manage symptoms, but because they mistakenly believe that cannabis has anti-cancer properties.

“This may be perhaps more of an emotive response out of a sense of desperation, flamed by irresponsible marketing and promotion as the clinical evidence does not support cannabis as anti-cancer presently.”

A systematic review by Canada’s Drug and Health Technology Agency published in 2019 on the effectiveness of cannabis in palliative care was “unable to draw conclusions due to the low quality and quantity of evidence surrounding the use of medical cannabis in the palliative care setting. Medical cannabis was found to be superior to placebo for appetite and weight gain in palliative patients with HIV, however mental health adverse effects were increased.”

This misguided public perception of cannabis as “anti-cancer” isn’t unique to Malaysia. The 2021 research previously cited by Dr Cardosa on Thailand’s experience reported that in a survey of 118 patients at the Pain Clinic at Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok, 20 per cent of patients polled believe that cannabis can cure cancer. Only 28 per cent of patients believe that they have enough understanding to use cannabis-based products.

Cancer Group: Cannabis Must Be Held To Clinical Standards Like Other Drugs

Dr Murallitharan Munisamy, managing director of National Cancer Society Malaysia (NCSM), said he only supported the legalisation and use of cannabis for medical purposes in cancer provided there is strong evidence for its safety and effectiveness.

He pointed out, however, that there are only a very small number of limited clinical trials across the globe that can provide good data on a drug’s efficacy and safety.

“So, if you are going to treat it as medicine, it needs to be held up to the medical standards,” Dr Murallitharan told CodeBlue, referring to cannabis.

“It needs to be able to adhere to medical criteria which are proven in a clinical trial,” added the public health physician. “It needs to be able to be proven to do so in a clinical trial setting like any other drug.”

When a drug undergoes clinical trials, it is subject to a three-phase test to identify the appropriate dosage, to test for side effects, and to determine if the new drug is safe and effective for people, before it can be approved for use. Clinical trials start with a small group, about 20 to 80 people in the first phase, before increasing the number of test subjects to as many as 3,000 people in the third phase.

This emphasis on clinical trials and evidence is something that Dr Murallitharan strongly insists on as he believes that physicians are not the ones driving the push to legalise medical cannabis in Malaysia, but rather, commercial entities.

“And commercial entities over the history of our entire industrialised period of humanity have never had any kind of qualms in just doing whatever they want to drive profits. Being very aware that this is a drug that has very highly addictive components, I would still think a lot of careful work needs to be done to be putting it into the medical therapeutic space,” said Dr Murallitharan.

However, he welcomed Khairy’s move to bring in cannabis through the “medical space”.

“If the minister is taking the first step, it is a good first step because to be fair, it is actually a very mirroring strategy that the MOH has taken in terms of vape. We have to have a discourse, we have to have a legal discourse.

“And look at the end of the day, unlike vape, with marijuana, it’s a very grey area. We don’t know the evidence, but it is worth testing it, bringing it in legally, and having a proper framework to assess and utilise it if it is beneficial.”