Health is a macro-critical economic, social, and political opportunity, but neglect of this sector poses risks now and for the future. Health care, both public and private, is a significant and growing part (≈1/20th of GDP) of Malaysia’s economy, representing not only the government’s investment in human capital (≈9% of the federal budget) but also a key economic growth area.

High-income countries, a group Malaysia is poised to join, spent 12.6 per cent of GDP on health.

Health is also a ‘special’ good, fundamental to the wellbeing, full potential, and cohesiveness of all Malaysians in expressing our humanity and aspirations, and as productive participants within our families, workplaces, and communities.

The macro-criticality of health is echoed by global institutions – even the International Monetary Fund now concurs that “public investment in health and education boosts productivity and growth, and reduces inequality of opportunity and income” and “increase[s] the resilience of lower-income households to economic shocks … which are expected to become more frequent and disruptive”.

Furthermore, public discontent with its affordability, quality, and waiting times is gaining volume. Although ‘free’ health care is provided by the federal government, some state governments are enhancing their own political legitimacy by filling in health care access gaps.

The health reform agenda has been stalled for decades. Given the importance of health, at least 14 studies have been commissioned since 1985, the most recent was conducted as a collaboration between the Ministry of Health (MOH) and Harvard University.

Despite unanimous consensus on the need to reform Malaysia’s health system, critical recommendations and reforms have not yet been delivered.

Malaysia’s health system performance has deteriorated in this current century, having performed relatively well the century before. This is due not only to insufficient investments in health and an unsustainable health financing model, but to an outmoded health care delivery system that does not create value for patients, especially those with chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

In Part I, we alluded to the critical role of social determinants of health and the urgent need for a whole of government approach, driven by a health-in-all-policies philosophy.

Until and unless this is prioritised and addressed, the nation’s health agenda will be defective, health inequalities will persist and people’s well being will be compromised.

We suggested the three major areas in the health care system which needs to be reformed in in order to achieve a health-empowering ecosystem.

There needs to be bold, system-wide reforms which involve the transformation of the public health care delivery system. This must be coupled with regulatory reforms to establish a value-based private health care milieu.

And these health care delivery reforms will need to be financed sustainably by health financing reforms. Such financing reforms in synergy with public sector and private regulatory reforms will enable the establishment of the paradigm of a technology-native, person-centered integrated healthcare model based on choice and value.

Although in the previous century, Malaysia — an ‘Asian tiger’ — used to be an over-performer in the arena of health, Malaysia’s performance in recent years has been less flattering.

Malaysia is increasingly trailing behind comparator countries such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and New Zealand on the measure of life expectancy for males at the age of 60, a proxy measure of NCD management.

Compared with Malaysia, these countries are improving at a faster rate and from a higher starting point, resulting in a widening gap. Considering that it would be easier to make gains in life expectancy from a lower starting point — e.g., it is easier to improve life expectancy from 60 years to 70 years, than it is to improve it from 70 years to 80 years — this performance gap is sobering.

Similarly, health disparities within Malaysia are widening. More embarrassingly, even where Malaysia has traditionally been strong – maternal and child health (MCH) — Malaysia has not made further progress in the current century

A reformed health care delivery model is required even if financing was sufficient. This is due to the epidemiological transition to NCDs which span the life course, the need to care for an aged, urbanised populace, and to manage rising middle-class expectations while leveraging the opportunities made available by technology.

NCDs are life-long and may be asymptomatic initially, in contrast to communicable diseases, which are acute and episodic. Public health initiatives, across different sectors, levels of government, and society – i.e., a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach is paramount to reduce the risk factors for NCDs, which include dietary, lifestyle, and environmental factors.

Within the health sector itself, the provision of necessary preventive and curative care in an effective, high-quality, and accessible manner requires the coordinated involvement of multiple specialties and facilities.

Doctors, clinics, and hospitals working in isolation is not the solution. Human resources for health are also a critical constraint, as there are challenges with the quality and distribution of health personnel, driven by underlying difficulties with recruitment, training, and retention.

To address all these challenges, a reformed model will have the person (rather than facility or doctor) at the center and be proactive at preventing disease and promoting health in a cross-sectoral, integrated, comprehensive, and coordinated a manner – i.e., a technology-native, person-centered integrated care model, based on value and choice, supported within a health empowering ecosystem.

Health investments, specifically, pooled and prepaid financing are insufficient. Prepaid financing is critical for prioritising prevention instead of cure, and as a powerful reform lever for health care delivery and to negotiate the best quality for the lowest price using strategic purchasing.

Pooled financing is critical for allocating resources efficiently and for health equity due to the mismatch in means and needs between the healthy and sick, and the wealthy and poor.

Pooled and prepaid financing has been persistently low (at least since National Health Accounts began in 1997). Why this is the case will be examined for the two main sources of pooled and prepaid health financing:

Federal government expenditures. The health system remains dependent on the federal government budget, but this is decreasing and untargeted, subsidising rich and poor alike.

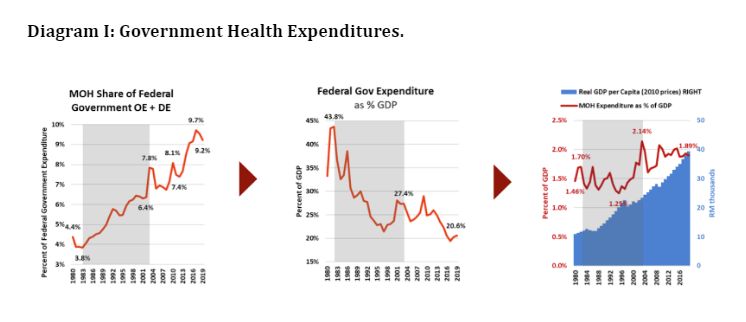

- From 1982 to 2003, the proportion of the federal expenditures through MOH more than doubled from 3.8 per cent to 7.8 per cent. Hence, although there was a steep decline in federal government expenditure as a proportion of GDP by 2003 the share of the MOH budget was increased to 2.1 per cent of GDP, the highest ever for Malaysia. Unfortunately, after 2003, government investment in MOH is projected to fall to 1.9 per cent of GDP by 2019. (see Diagram I)

- The government has rightly aspired to increase its investment in health to an ambitious target of 4 per cet of GDP. But, given how the trust deficit has already shrunk federal government expenditures, there is no realistic option to increase investments in MOH solely through the federal government budget alone.

- This financing is also channeled through a line item budgeting system which does not give local health managers the autonomy or incentive to make savings or to improve quality or expand service coverage. Prioritisation based on policies, such as the intent to prioritise primary health care and public health, have also been unrealised by this budgeting system. Instead, curative care and hospital services continue to receive an ever increasing budgetary allocation in response to short term pressures.

Voluntary prepayments include private health insurance and employer health coverage plans which use managed care organizations (MCOs) in a lightly regulated market.

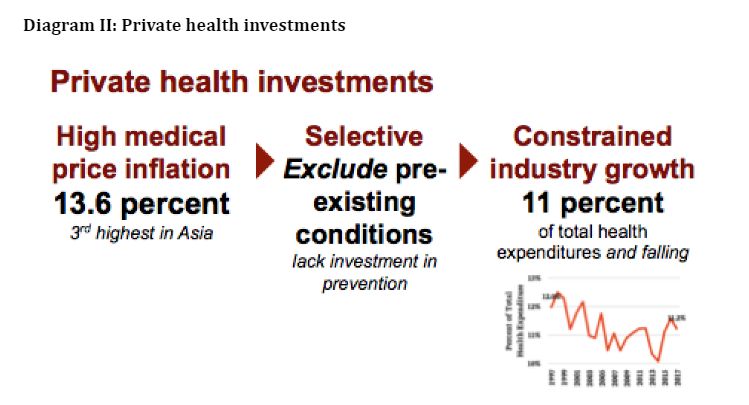

- Private health insurance remains a small and falling proportion of total health financing — falling from 12 to 11 per cent in the last 20 years, as it is focused on the healthy and wealthy. Furthermore, the lack of strategic purchasing to incentivize prevention, quality, and value-based healthcare has resulted in medical price inflation of 13.6 per cent projected for 2019, third highest in Asia. This threatens the aspirations and value of middle-class income gains and retards the growth and affordability of private insurance, noting the low penetration rate of life insurance. (see Diagram II)

- Employers also are exposed to costly health care and poor value. Employers spent more than RM11,000 per year on average for employee hospitalisation and surgical insurance premiums for Malaysians and RM762 per year on average on employee outpatient expenses in 2015. Expenditures are focused on costly curative services, rather than investments in disease prevention and management. In addition to direct healthcare costs, indirect economic costs of NCDs from lost productivity and premature death can be substantive — e.g., US$ 45,959 per person with diabetes.

Given the lack of pooled and prepaid health financing, Malaysians spend a lot in an ad hoc manner. Out-of-pocket (OOP) payments are very high (RM 673 per capita per year; RM 2,827 per household of 4.2 people per year; 38 per cent of total health expenditures).

Even though OOP is concentrated mainly among the wealthier quintiles and hence the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures is relatively low in Malaysia, this form of financing has major weaknesses as ad hoc purchasing by individuals lacking market power or expertise are exposed to the risk of low-value and poor-quality services due to market failures such as information asymmetries.

Furthermore, the lack of pooling or prepayment precludes the prioritisation of prevention and efficient, equitable matching of needs to means.

A fragmented health financing system leads to fragmented, low-value health care, characterised by duplication of services and an uncoordinated healthcare delivery system which is focused on ad hoc demands for curative care, rather than comprehensive and coordinated management of NCDs over a life course.

This fragmented financing system contributes to silos in the delivery system as, by and large, public financing goes to public facilities and private financing goes to private facilities. This is a key weakness of the current health financing system.

The past studies share several common elements, including the need to address underfunding and the sustainability of health financing, to use financing and payment levers to allow the participation of private providers in a high-quality and value-based manner, while empowering autonomous public providers to compete on a level playing field with private providers.

The reforms which we propose builds on the consensus from these past studies and incorporates in an eclectic manner global best practices contextualized and aligned with the core ethos of the nation as expressed from the birth of the nation in the Rukunegara, which nurtures the ambition of “creating a just society where the prosperity of the country can be enjoyed together in a fair and equitable manner” and to embrace Malaysia’s health-specific vision which enshrines the principles of equity, accessibility, affordability, and efficiency.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.