The growth of children in the first five years of life is closely related to nutrition. Hence, if nutritional status is not optimised, the children in our country would be at a disadvantage, and we will continue to see rises in the prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight children.

Based on NHMS 2011 and NHMS 2015 data, all three parameters showed a downward trend. However when comparing NHMS 2015 and MCHS 2016, all three parameters showed a rise in their respective prevalences.

The national prevalence in 2015 of stunting, wasting, and underweight Malaysian children was 13.4 per cent, 7.9 per cent, and 13 per cent respectively; compared to 20.7 per cent, 11.5 per cent, and 13.7 per cent in 2016. This is undoubtedly a most worrying trend.

Stunting is the impaired growth and development that children experience as a result of long-term or chronic poor nutrition, repeated infections, and inadequate psychosocial stimulation.

Hence, improving their nutrition starting from exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life, followed by optimum complementary feeding practice in the first two years of life and optimization of family-based diet for those aged 2 to 5 is the way to go.

Studies have shown that children aged 8 who recovered from early age stunting, performed better in mathematics, reading, and vocabulary comprehension than those who stayed persistently stunted.

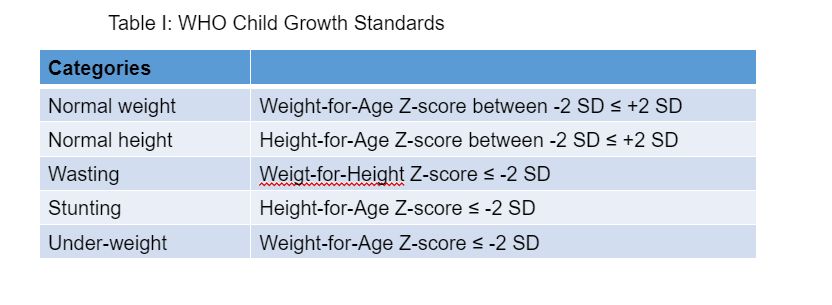

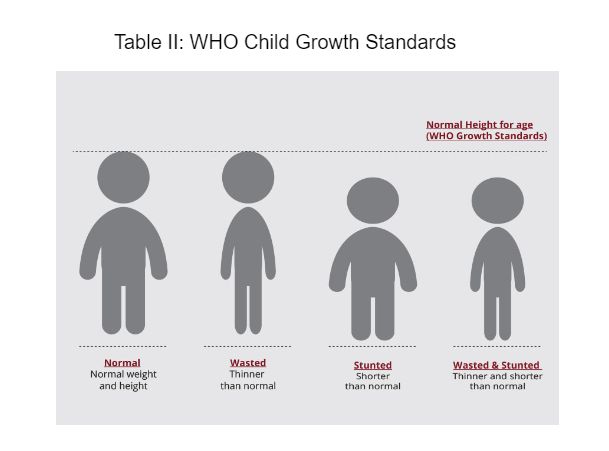

Children are defined as stunted if their height-for-age is more than two standard deviations below the WHO Child Growth Standards (see Tables I and II).

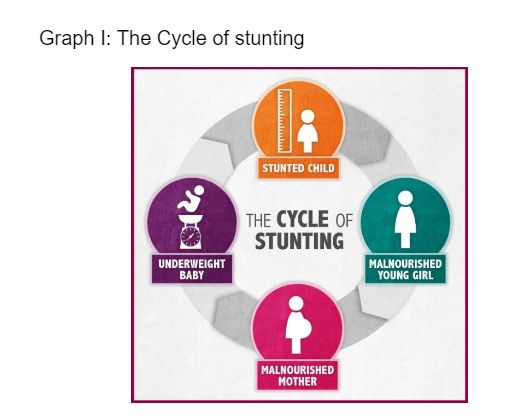

Stunting affects the whole life cycle of a person, and a number of preventive measures are needed.

Good antenatal care is important. According to MCHS 2016, those at risk are aged between 15 and 24, “other” ethnic groups, non-citizens, and mothers with lower education and lower income.

These groups of women had a higher prevalence of no antenatal care, adequate basic requirement of antenatal visits, as well as late booking in the third trimester, and only a few had early booking in the first trimester.

Emphasising pre-pregnancy counselling, early booking, and follow-ups in these women will ensure a better pregnancy outcome, along with good quality antenatal care. Patient-doctor communication in improving health-seeking behaviours will further improve the service by better acceptance from high-risk groups.

Early identification, appropriate management, referrals, and documentation should always be strengthened. Marketing and awareness of the pre-pregnancy care is of utmost importance to improve maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, and help mitigate the vicious cycle of stunting (see Graph I).

Improving rate of exclusive breastfeeding. According to MCHS 2016, the overall prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among infants under six months old was 47.1 per cent.

By ethnicity, the highest prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding was among Malays (48.9 per cent), followed by other Bumiputeras (46.0 per cent), Indians (41.8 per cent), and Chinese (29.6 per cent).

This prevalence can be improved by establishing a more supportive breastfeeding environment, especially at workplaces and public places, and increasing the availability of facilities to breastfeed or express breast milk, and to store expressed breast milk for working mothers.

Mandating an adequate period of paid maternity leave of at least three months for working mothers to improve exclusive breastfeeding rate is also important.

Improving complementary feeding practice, i.e. improving the dietary diversity, meal frequency, minimum acceptable diets, and food groups among children up to 23 months old.

The overall prevalence of children with minimum meal frequency (children who received solid, semi-solid and soft food for breastfed and non-breastfed children) was 80.8 per cent, minimum dietary diversity (children who received foods from four or more food groups during the previous day) was 66.4 per cent, and minimum acceptable diet (children who breastfed at least the minimum dietary diversity and minimum meal frequency during the previous day for breastfed and non-breastfed) was 53.1 per cent.

Although this figure is much better than the ones in UNICEF’s Global Report 2020 among Low and Middle Income Countries (LMIC), the percentage of children aged 1 to 6 not meeting the food group intakes is worrying.

More than 50 per cent did not fulfil the recommended servings of meat and poultry, fish and milk and dairy products (proteins) that are essential for growth (Zalilah MS, Nutrition Research and Practice 2015).

Hence, it is important to create awareness among parents and caregivers about the importance of dietary diversity for children under 2, and to provide specific infant feeding training to health care providers.

Apart from that, we also need to educate parents and caregivers on how to fulfil dietary diversity requirement and food groups, based on family diets for children aged 3 to 6 in order to improve their nutritional status.

Improving health monitoring especially among children between 2 and 5. Despite the availability of free access to health care for children aged 2 to 5 years at Maternal and Child Health Clinics (MCHC), only a small portion of parents use this facility.

Children up to 6 years old attending health clinics undergo scheduled assessment and monitoring for general health status, growth, and development. The expected norm for scheduled assessment is nine visits for infants, four visits for toddlers, and two visits for preschoolers.

According to the Family Health Development Division Annual Report 2018, 75 per cent of children under 1 year old attended the health clinics, while attendance for toddlers aged 1 to 3 was 48.3 per cent, and pre-school children was 24.1 per cent.

Health care providers and parents should be educated on the importance of “healthy-child clinic”, especially for children aged between 2 and 5, so that any growth issues in this age group can be identified early.

Psychosocial stimulation: According to MCHS 2016, surprisingly, only slightly more than half of Malaysian parents sent their children to early childhood education programmes.

In addition, only one in four engaged actively with their child in various activities that promote learning and school readiness.

It appears that higher levels of education and earning capacity in parents enable them to send their children to early education programmes, and procure children’s books and toys.

However, it also seems that the same group of parents spend lesser time than others in spending time with their children, reading, writing, singing, or playing with them.

Parents of lower socioeconomic groups appear to engage more with their children. Parents’ engagement has been shown to also affect the nutrition of their children.

Authoritative parents are more successful in improving the diet quality of their kids, compared to those who are authoritarian, permissive, or neglectful.

However, we need to acknowledge the following challenges and overcome them, namely:

- Lack of inter-sectoral and multi-stakeholder coordination.

- Financial shortfall and lack of sustainable financial commitment.

- Lack of capacity.

- Lack of monitoring and evaluation.

Our country has a wide array of natural resources, including fertile land for agriculture, and also livestock and fisheries industries. Despite this, our children are still not getting enough nutrition, due to two major challenges, namely food security, its availability and accessibility, and knowledge of dietary diversity.

In terms of food security, availability, and accessibility, the cost of fruits and vegetables, and fish, meat, and poultry are high, and accessibility is very limited.

This is mainly related to high costs of transport and the middle-man syndrome, and this problem was amplified during the Covid-19 pandemic The government needs to actively look into this, and a strict policy needs to be implemented.

When it comes to knowledge about dietary diversity and food groups, it is important to educate health care providers, parents, and caregivers on how to fulfil dietary diversity requirements for children under 2 years old, in order to improve nutritional status and prevent stunting among children within this age group.

For children aged 2 to 5, family-based diets also need to be improved, following the recommended nutrient intake (RNI) that was revised recently in 2017.

There are a number of complications that may arise from growth problems during early childhood. The short-term problems include impaired brain development which may lead to lower Intelligence Quotient (IQ).

Undernourished children also may have a weakened immune system which may lead to recurrent infections, hence further worsening normal growth.

In the long term, these children may have smaller adult stature and lower productivity (due to lower IQ and academic performance). Stunted children have an increased risk of becoming overweight and obese adults, which increases the risk of diabetes, cancer, and premature death.

Table III illustrates the lifetime costs of stunting.

When we discuss stunting, this is mainly related to children below 5 who have not started school. However, the problem of short statures may continue if problems related to nutrition are not sorted out before they enter school.

At school-going ages, other than nutrition, sleeping time, physical activity, and psychosocial stimulation need to be looked into, so that growth is optimised.

As we said earlier, there is a lack of inter-sectoral and multi-stakeholder coordination to address the issue of childhood malnutrition. All agencies need to work together.

It is not just the job of the Nutrition Division of the Ministry of Heath. It is everyone’s job.

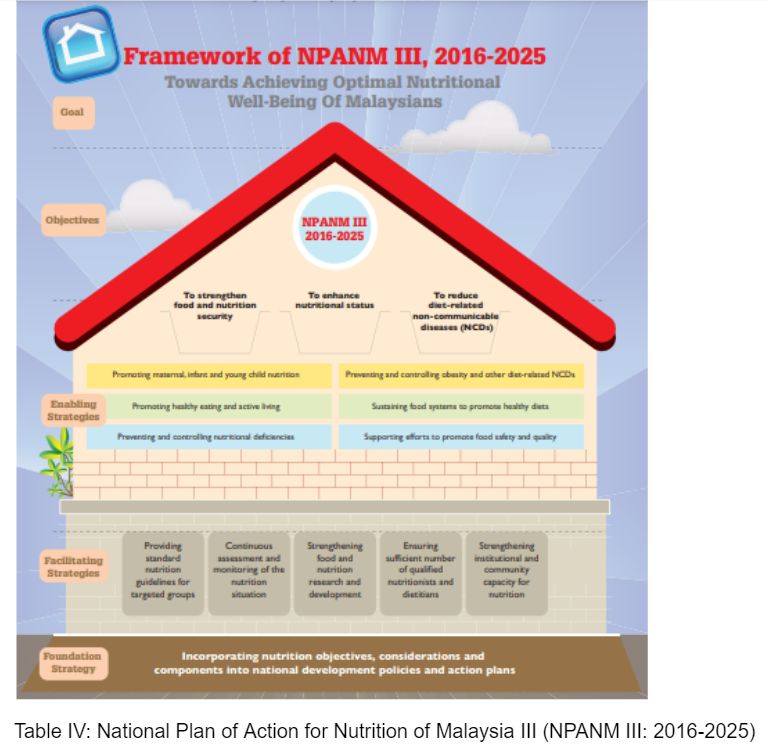

The National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCCFN), through the National Plan of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia III (NPANM III; 2016-2025) has outlined a few activities and programmes to overcome this issue, including:

Nutrition surveillance: Periodic surveillance includes weight for age, weight for height, height for age, and Body Mass Index (BMI) for age to be strengthened, and parents need to be informed of the outcome of the surveillance.

Rehabilitation programmes for malnourished children: This has been implemented since 1989. Basic food supply to ensure food and nutrition security, immunisation, health education on child nutrition, and personal hygiene need to be strengthened. Community feeding programmes that specifically rehabilitate undernourished children from marginalised groups needs to be improved.

Nutritional activities at child care centres: Nutritionists are now involved in the development of menus and recipes at government child care centres. Caregivers are trained to carry out the monitoring of nutritional statuses. The result of must be made known to parents so that early and appropriate action could be taken.

Prof Dr Muhammad Yazid and Dr Musa Mohd Nordin are from the Malaysian Paediatric Association.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.