KUALA LUMPUR, May 13 — Nearly nine of 10 Covid-19 cases in Malaysia the past month were sporadic, which means that authorities do not know how these people got infected.

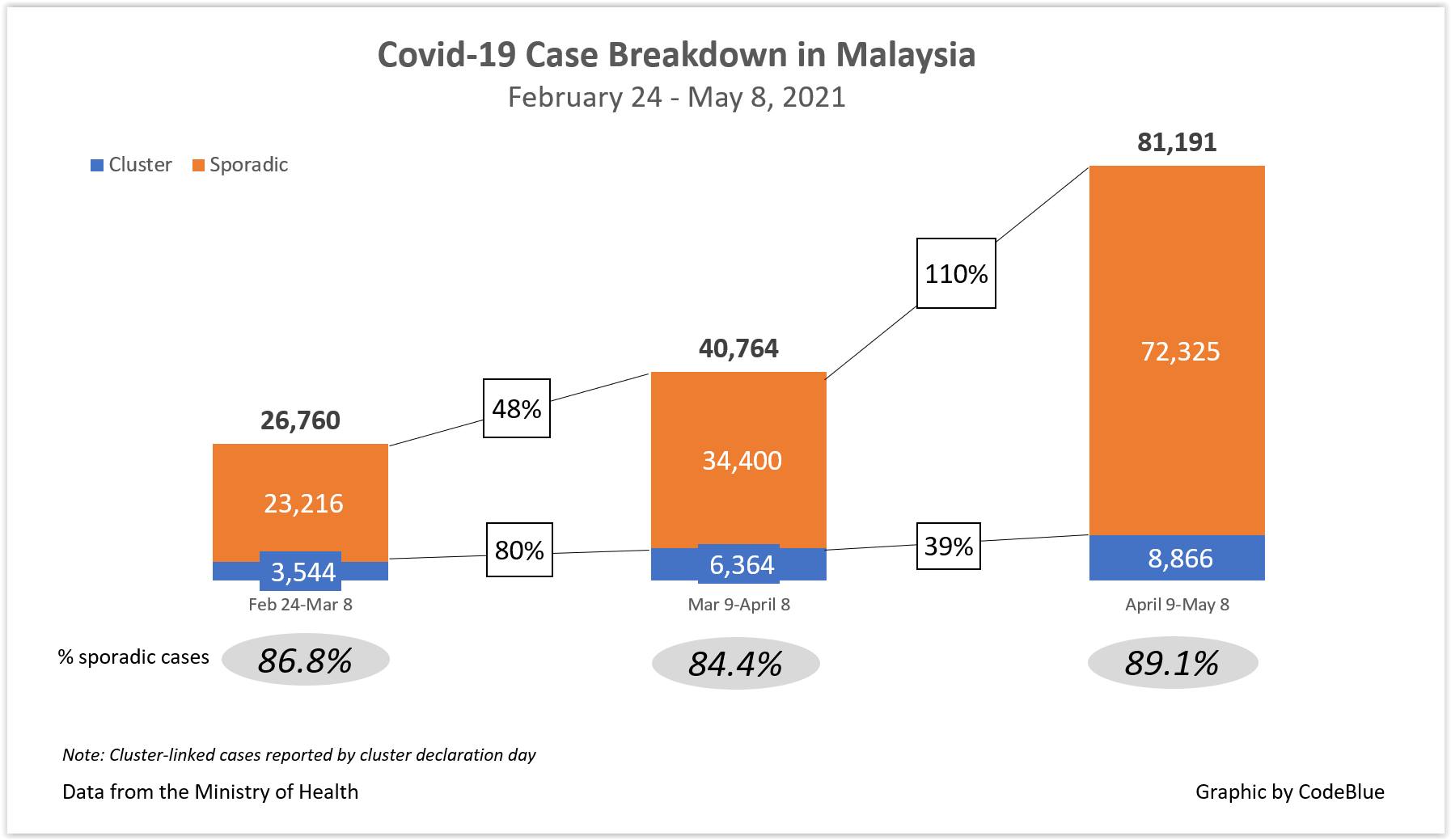

The astounding 89.1 per cent sporadic rate from 81,191 new Covid-19 cases reported from April 9 to May 8 — or 72,325 unlinked infections — shows a complete breakdown of the country’s testing and contact tracing protocols.

There is no such thing as a truly “sporadic” or “unlinked” case in infectious or communicable disease. A person with Covid-19 got the infection from someone else. Having unlinked cases is a way of saying that the source of the spread is not known.

If investigators are unable to determine a link between one Covid-19 case and another, this means that they couldn’t track people, who had either given or contracted the infection from that case, and isolate them before they infect others.

Since people with Covid-19 can transmit the disease before they develop symptoms, such undetected cases may unknowingly infect other people, who go on to spread the disease to their contacts and so on, leading to multiple generations of spread before (or if) they are ever detected.

According to Ministry of Health (MOH) data, sporadic cases made up 86.8 per cent of 26,760 new Covid-19 infections reported nationwide in two weeks from February 24 to March 8, before dipping slightly to 84.4 per cent of 40,764 new infections reported in the month of March 9 to April 8.

The proportion of unlinked cases then rose to 89.1 per cent of 81,191 new infections reported nationwide in the following month of April 9 to May 8. The number of both new and sporadic Covid-19 cases in Malaysia doubled in the past month from the previous month. In the past 10 weeks from February 24 to May 8, unlinked cases comprised 87.4 per cent, or 129,941 of 148,715 total new infections.

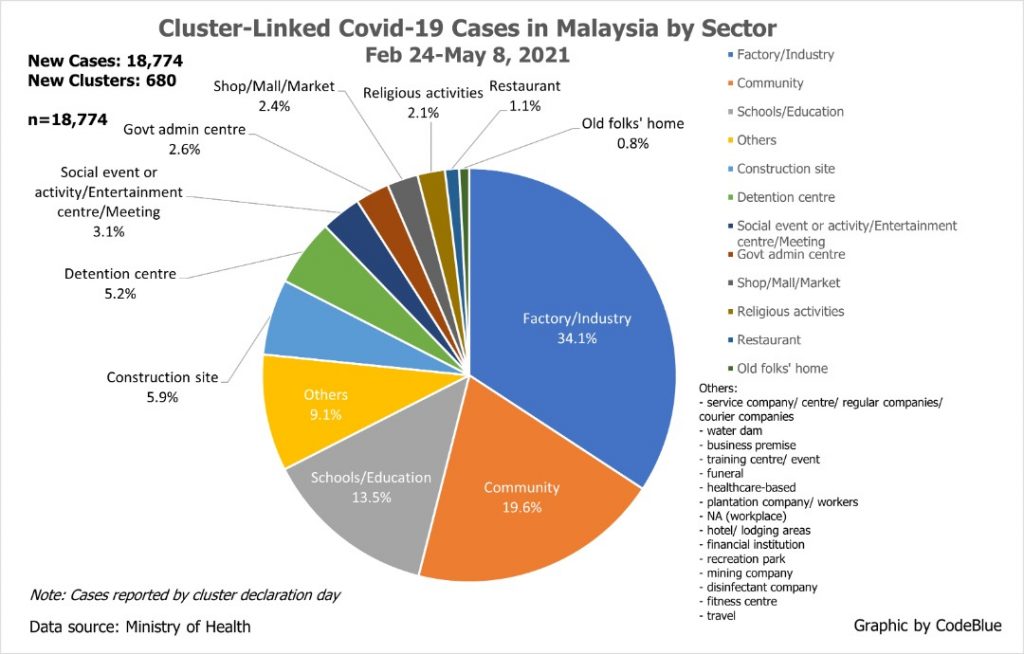

We calculated the number of sporadic cases by tracking the number of Covid-19 cases linked to reported clusters. These cluster-linked cases were calculated by the day a cluster was reported. In most instances, the largest share of cluster-linked cases occurs by the time a cluster is officially announced.

Very few additional cases are added to a cluster after the cluster is declared, except in notable cases like the Teratai cluster that originated from a glove manufacturing company last year. Hence, the proportion of cluster-linked versus sporadic infections in this analysis are likely representative of overall data.

Health director-general Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah told a press conference Tuesday that 80 per cent of “recent” Covid-19 cases in Malaysia were sporadic, or not associated with any cluster. He did not give a time frame for the statistic.

So what constitutes a “cluster”? There is no official definition in MOH protocols; a cluster may be defined by investigators on the ground from as few as two linked Covid-19 cases, or at least 10 to 15 linked cases.

We do not wish to speculate on how health authorities let Covid-19 — a virus which was recently acknowledged by the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an airborne pathogen — spread rapidly through the community, beyond the control of contact tracers.

Sporadic Covid-19 cases had actually begun spiking since last October, initially concentrated in Sabah following its state election campaign, a super-spreader event. Unlinked transmissions were already brewing silently in the state for weeks before the September 26 poll.

Seven months ago in October, Malaysia recorded below 1,000 daily Covid-19 cases. Now, the nation records quadruple the coronavirus infections amid the spread of new variants, reaching an average 3,621 daily cases from May 2 to 8. Malaysia added 4,765 cases yesterday, the highest 24-hour tally since January 31.

Malls And Factories Jointly Contribute Below 5% Of Overall Cases

Despite the near-90 per cent proportion of sporadic Covid-19 cases, the government’s public health interventions still focus on the minority 10 per cent of infections from clusters.

The HIDE predictive analytics system — which the government claims is able to predict Covid-19 hotspots before they occur by relying on check-ins with the MySejahtera app — has largely targeted high-traffic malls and supermarkets in the Klang Valley.

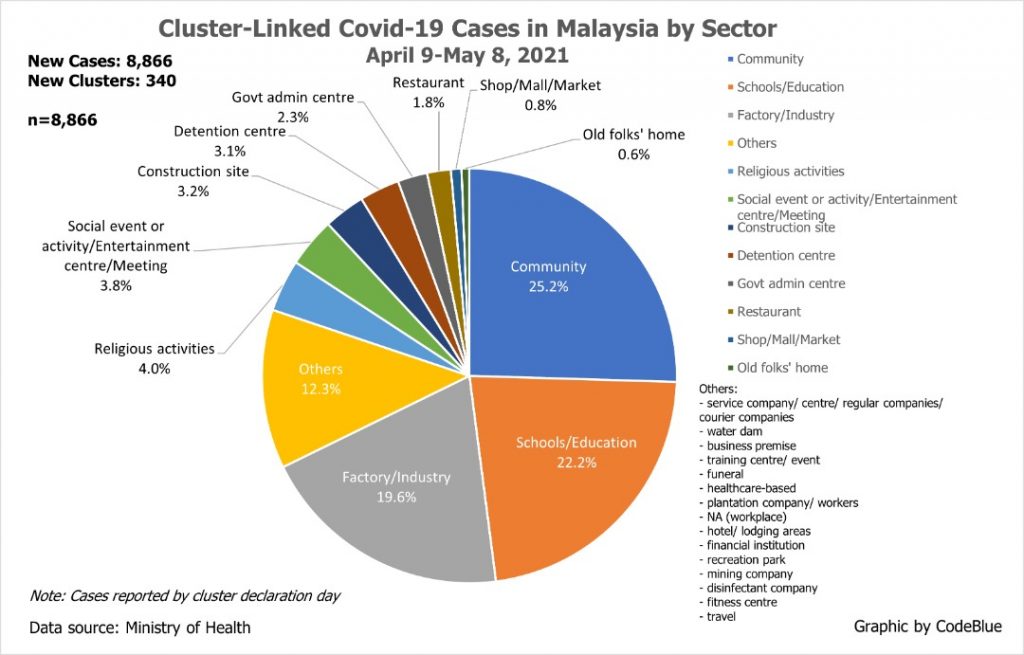

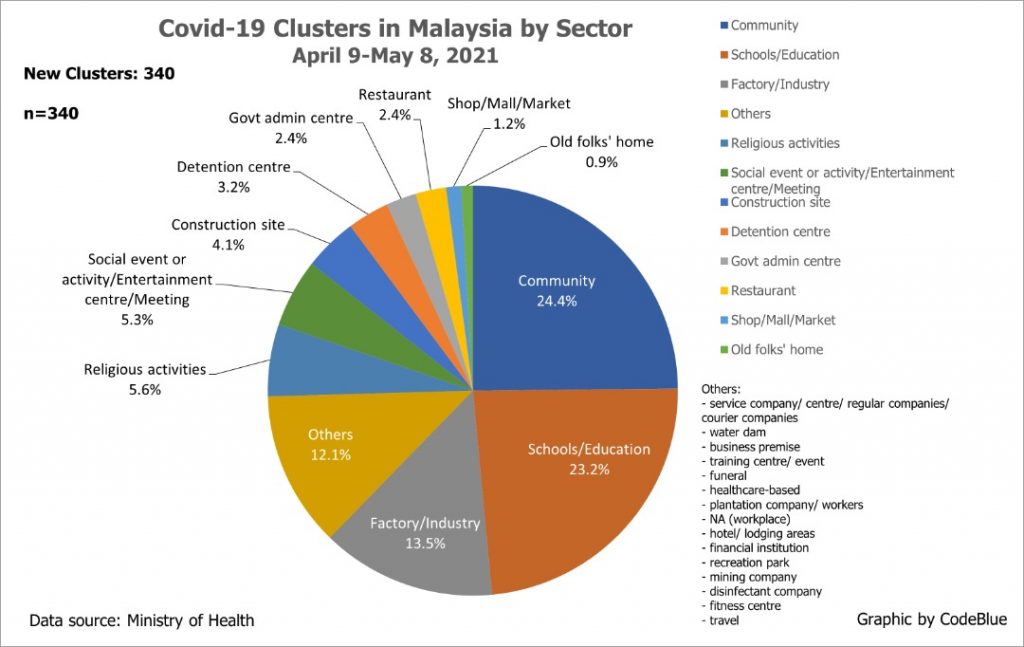

Yet, shops, malls, and markets combined only contributed 0.8 per cent of 8,866 Covid-19 cases from 340 clusters reported nationwide from April 9 to May 8. These 8,866 cluster-linked cases formed only 10.9 per cent of 81,191 total infections that past month.

In other words, shops, malls, and markets combined only contributed 0.09 per cent of Malaysia’s 81,191 new coronavirus infections reported the past month, or fewer than one out of a 1,000 cases.

The three-day closure announced by the National Security Council (NSC) on premises listed on HIDE led to sanitation and disinfection, a fundamentally pointless activity that only benefits cleaning companies as the coronavirus is transmitted by people. The US CDC said last month that the likelihood of contracting Covid-19 from touching contaminated surfaces (fomite transmission) is low at less than one in 10,000. Hence, when these premises reopen, asymptomatic patrons will bring the virus along with them.

From April 9 to May 8, community clusters contributed the highest number of coronavirus infections at 25.2 per cent of 8,866 cluster-linked cases from 340 clusters, followed by schools or the education sector (22.2 per cent), and factories or industries (19.6 per cent).

Community clusters refer to linked Covid-19 cases found in the community, such as from Covid-19 screenings for symptoms like influenza-like illness (ILI) and severe acute respiratory infections (SARI), community screenings, hospital admission screenings, and voluntary screenings, among others.

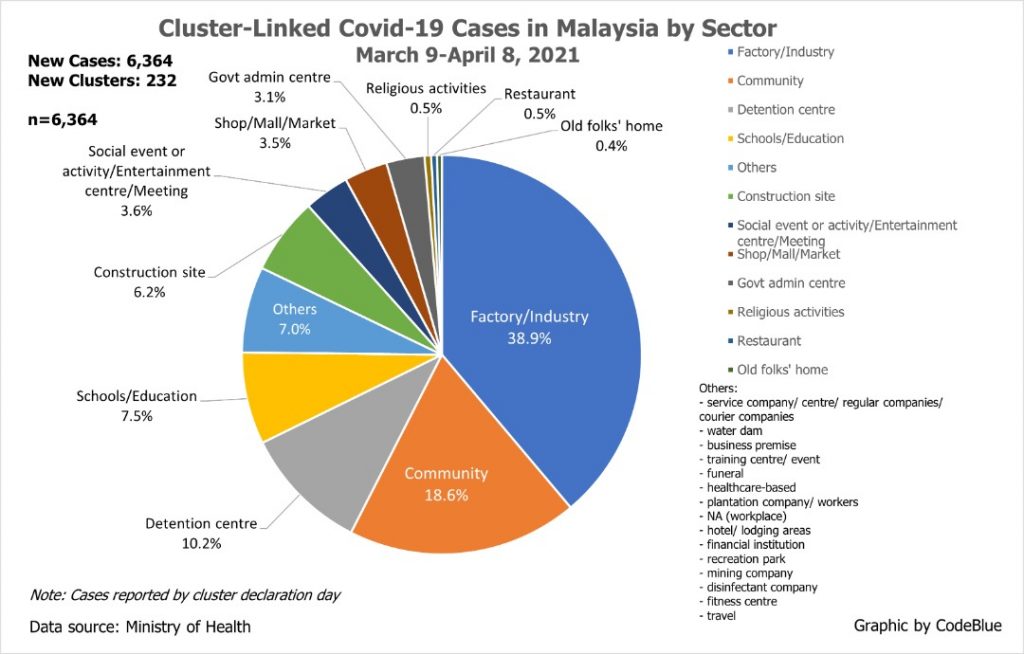

The previous month from March 9 to April 8, factories or industries contributed the largest share of cluster-linked cases at 38.9 per cent of 6,364 Covid-19 cases from 232 clusters, followed by community clusters (18.6 per cent), and detention centres (10.2 per cent).

Again, it bears reminding that these 6,364 cluster-linked infections only formed 15.6 per cent of the total 40,764 Covid-19 cases reported nationwide that month. In other words, factories or industries only contributed 6 per cent of total infections.

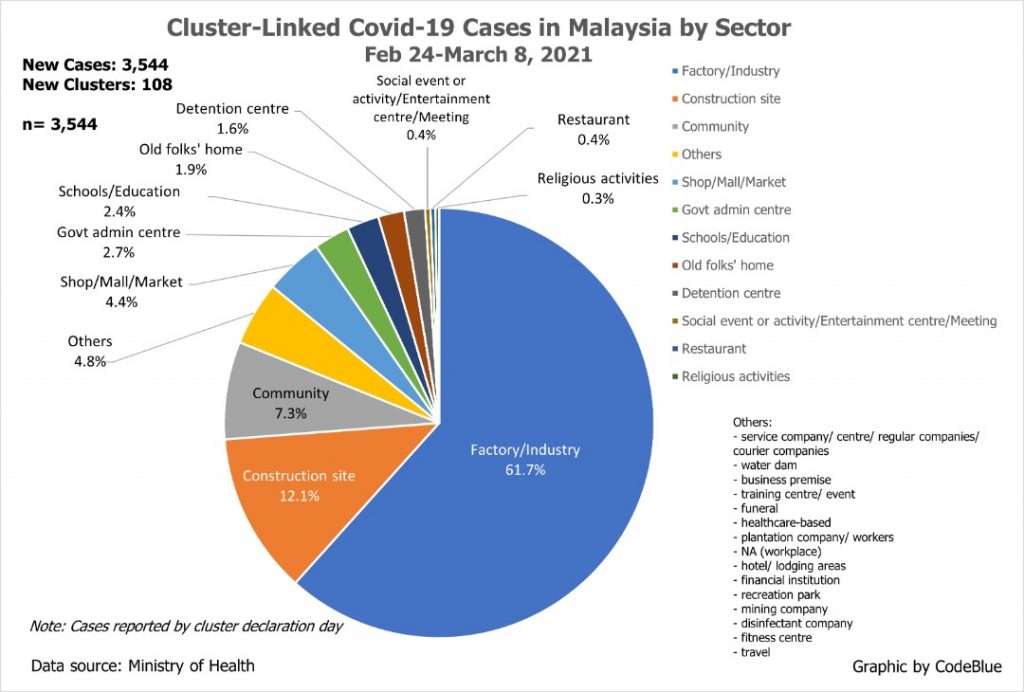

Factories or industries contributed 61.7 per cent of 3,544 Covid-19 cases from 108 clusters reported in the fortnight of February 24 to March 8. However, these 3,544 cases only comprised 13.2 per cent of the nation’s 26,760 infections in that period. Hence, factories or industries only contributed 8.2 per cent of total cases.

From February 24 to May 8, a total of 18,774 coronavirus cases were reported nationwide from 680 clusters, with these cluster-linked infections comprising 12.6 per cent of total new 148,715 cases in that 10-week period. Factories or industries comprised the biggest share of cluster-linked cases at 34.1 per cent, which means these premises only contributed 4.3 per cent of overall new infections.

It bears noting that the case contributions in clusters depends on testing. The government has made workers’ screening mandatory, although businesses are not required to periodically test their employees, only at least once. The fact that the proportion of cluster-linked cases from factories or industries fell from 61.7 per cent in the period of February 24 to March 8, to 19.6 per cent in the month of April 9 to May 8 illustrates the rising spread of sporadic infections.

The cluster data also proves that businesses in manufacturing and retail have largely succeeded in keeping Covid-19 infections outside their premises, at least in the past two and half months. The biggest problem is sporadic cases in the community.

Water dams and old folks’ homes reported high positive rates from April 9 to May 8 at 67.9 per cent and 62.1 per cent respectively. But when we assimilate the number of case contributions, number of clusters, and the positive rate (share of tests that are positive), the virus spread was actually biggest in factories or industries, followed by schools or educational institutions, and the community in the past month.

Detention centres, construction sites, and service companies must also be on high alert too as these premises are likely to report Covid-19 cases in future, based on combined data of case contributions, number of clusters, and positive rate. Authorities should target these areas for mass testing during the Movement Control Order (MCO) 3.0 and ramp up vaccination there.

Why Is Covid-19 Everywhere?

MOH’s Covid-19 case surveillance challenges is compounded by its own refusal to share data with public health experts outside the federal ministry or with state governments, including Selangor that is one of the main epicentres in the current outbreak.

Malaysia must ramp up testing and practice active surveillance with constant testing — one negative result today doesn’t mean the same negative next week. The solution is Find-Test-Trace-Isolate-Support (FTTIS) that Selangor is actively trying to do with digitised and automated contact tracing through the state’s SELangkah app.

The rapid spread of coronavirus throughout the community shows that people generally do not follow the basic public health interventions of physical distancing, masking, and hand hygiene. To be clear, most Malaysians probably practice these standard operating procedures (SOPs) in public spaces, especially in restaurants, shopping centres, and other retail establishments that are strict about masking and MySejahtera check-ins.

However, in private spaces across homes, offices (in both the government and private sector), and places of worship, many Malaysians likely don’t wear masks when they are in the company of family members from another household, friends, coworkers, or fellow neighbours. So, sporadic infections may have spread rapidly in these private spaces, unwatched by law enforcement.

For all the enforcement on SOPs in public spaces with punitive fines, throughout this entire pandemic, the Malaysian government has failed to set guidelines or limits on the number of people visiting our homes from outside our household — something which countries like the United States and Singapore have done.

We do not recommend regulating private spaces by enforcing MySejahtera check-ins before people can enter their own homes. The key to long-term behavioural change has always been health education, including good examples set by political leaders and senior members of government, not law enforcement.

With all that being said, it appears that the government may well be justified in imposing a third nationwide lockdown due to the sporadic spread of infections, if only to give a breather to hospitals across multiple states struggling to treat a surge of seriously ill Covid-19 patients.

But we still need clear post-lockdown measures. By myopically targeting Covid-19 clusters in public premises, the government is missing the forest for the trees.

This article was written by Boo Su-Lyn. “A Concerned Nationalist”, a medical doctor who requests anonymity due to the government’s gag order on civil servants, collated and analysed public MOH data for this analysis.