KUALA LUMPUR, May 15 — Malaysia still has malnourished young children and may only achieve one of 10 global nutrition targets by 2025, according to a report.

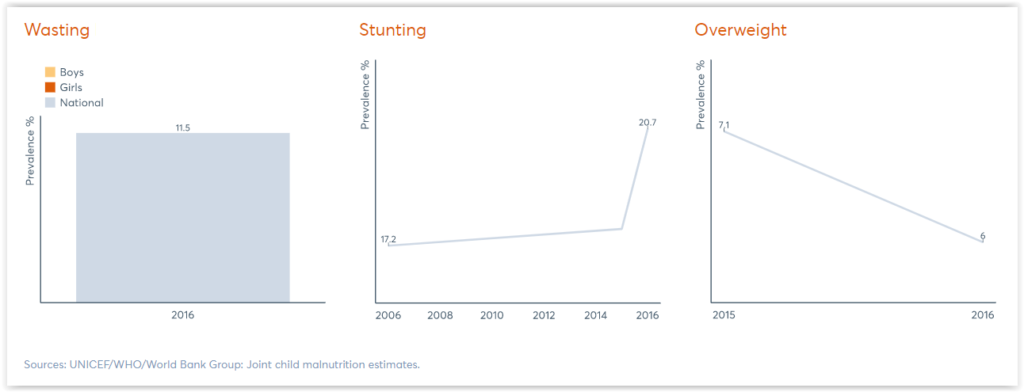

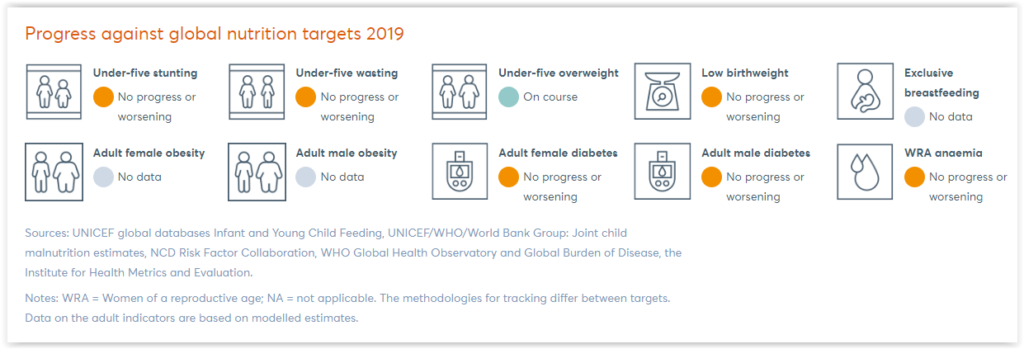

The 2020 Global Nutrition Report, which independently assesses the state of nutrition worldwide, found that Malaysia is on course to meet the global target for overweight children below five years of age, but is off course to meet the targets for stunting (low height-for-age) and wasting (low weight-for-height) among under-five children.

Malaysia also made no progress or is worsening in global targets for anemia among women of reproductive age, low birth weight, and adult diabetes in both women and men.

“Although it performs relatively well against other developing countries, Malaysia still experiences a malnutrition burden among its under-five population,” said the 2020 Global Nutrition Report.

The Global Nutrition Report showed that Malaysia’s national prevalence of under-five overweight was 6 per cent in 2016, a slight reduction from 7.1 per cent in 2015, but still ahead of the Asian region’s average of 5.2 per cent. The global target for childhood overweight is 5.5 per cent or less by 2025.

Malaysia is worsening in efforts to cut the number of stunted children under five, according to the Global Nutrition Report. Malaysia’s national prevalence of stunting in children under five years was 20.7 per cent in 2016, rising from 17.2 per cent in 2006. The developing country average is 25 per cent.

The global target for childhood stunting is a 40 per cent reduction by 2025 in the number of children under five who are stunted. Stunting is a serious malnutrition issue that is largely irreversible.

Malaysia’s under-five wasting prevalence of 11.5 per cent in 2016, according to the Global Nutrition Report, was higher than the developing country average of 8.9 per cent. The global targets for childhood wasting is less than 5 per cent by 2025.

There is insufficient target data to assess Malaysia’s progress for infant exclusive breastfeeding, male obesity, and female obesity, said the global report.

Malaysia’s adult population, however, also faces a malnutrition burden, according to the report. Almost a quarter, or 24.9 per cent, of women of reproductive age have anaemia, and 11.4 per cent of adult men have diabetes, compared to 10.7 per cent of women. Meanwhile, 17.9 per cent of women and 13 per cent of men have obesity.

According to the 2020 Global Nutrition Report’s executive summary, progress worldwide was too slow to meet the global targets. Not one country is on course to meet all 10 of the 2025 global nutrition targets, while only eight of 194 countries are on track to meet four targets.

“Almost a quarter of all children under five years of age are stunted. At the same time, overweight and obesity are increasing rapidly in nearly every country in the world, with no signs of slowing,” said the report.

Progress on malnutrition, noted the report, was “deeply unfair”, pointing out that underweight was a persistent problem for the poorest countries, whereas overweight and obesity were much more common in richer nations. Significant inequalities were found in malnutrition problems within countries and populations, according to location, age, sex, education, and wealth.

The previous Pakatan Harapan (PH) administration introduced a tax on sugary drinks last year. Although the Ministry of Education introduced “Healthy School Canteen Guidelines” in 2011 to ensure healthy diets in schools, a study in 2017 noted that 72.5 per cent of food in school canteens were carbohydrate-dominated whereas high-fat foods represented 38.4 per cent. The PH government had also launched a free breakfast programme for impoverished students in primary schools.

A study of urban child poverty and deprivation in low-cost flats in Kuala Lumpur conducted by Unicef showed that more than one in 10 children have less than three meals a day. Approximately 97 per cent of households living in low-cost flats are unable to prepare healthy meals for children, due to the high cost of food.

Poor nutrition for the first three years of a child’s life can lead to stunting. Exclusive breastfeeding practice for babies for the first six months of their life is one of the important ways to prevent stunting, overweight and obesity among children, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

As of 2016 in Malaysia, 40.3 per cent of infants under six months are exclusively breastfed, as cited by the Global Nutrition Report. According to the report, Malaysia’s low birth weight prevalence has risen slightly from 10 per cent in 2000 to 11.3 per cent in 2015.

The 2020 Global Nutrition Report shows that Syria, a war-torn country, recorded a higher prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 42.4 per cent compared to Malaysia. Malaysia has set a target of 70 per cent of babies being exclusively breastfed by 2025.

In the context of Covid-19, the report noted that undernourished people may have higher risk of developing severe disease from coronavirus. Obesity and diabetes are also linked to worse Covid-19 outcomes, including potential hospitalisation and death.

“People who already suffer as a consequence of inequities – including the poor, women and children, those living in fragile or conflict-affected states, minorities, refugees and the unsheltered – are particularly affected by both the virus and the impact of containment measures.

“It is essential that they are protected, especially when responses are implemented,” wrote the Global Nutrition Report’s Independent Expert Group.