My mother recently told me about the plight of a village in the interiors of Sabah, where a man begged a community organiser to buy his mangoes so that he could buy rice. Apparently, more than 70 families in the Sabahan village were going hungry, as government aid wasn’t reaching them. But they have since managed to get some help from Christian groups.

It’s not only Malaysians living in remote areas of East Malaysia who are going hungry during the nationwide Movement Control Order (MCO) that is set to last for eight weeks until May 12. Public housing residents living in PPR flats in Kuala Lumpur and Petaling Jaya, who were already poor even before the Covid-19 crisis hit Malaysia, are running out of food and essentials, as the lockdown prevented odd job workers and the self-employed from working. Some roadside food stall operators — forced to shutter during the MCO, unlike restaurants and fast food chains that can continue operating through takeout delivery – have reportedly skipped meals so that their children can eat.

A police officer from Kulim, Kedah, decided to help instead of arrest a Pakistani man, who was stopped at a roadblock while travelling to Lunas to borrow money from a friend, as his wife and three children had not eaten for two days. The Pakistani man was reportedly forced to shutter his small business in Penang because of the lockdown.

These are accounts of self-employed workers – both Malaysian citizens and foreign nationals – who are starving as the MCO drags on for two whole months until May 12. The only privileged people who can afford to lock themselves up at home for eight weeks or longer, with large stocked larders, are salaried professionals that continue receiving pay from their bleeding employers – that is, until they possibly get laid off.

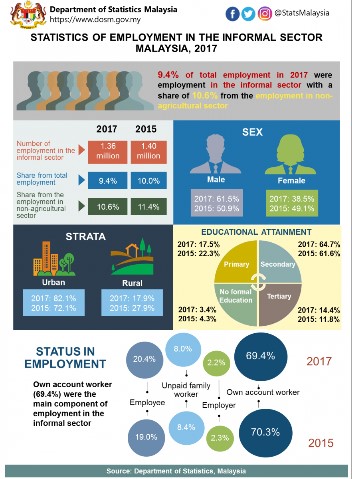

According to the Department of Statistics, 1.36 million people were employed in the informal sector in 2017, comprising 9.4 per cent of total employment in Malaysia. Two-thirds of informal workers in 2017 laboured in the services industry (62 per cent), followed by construction (20 per cent), and manufacturing (17 per cent). However, it is not only self-employed and informal workers who may lose their income during the prolonged lockdown.

Employers and industry groups have predicted that about two million Malaysians could be retrenched, as the government’s wage subsidy of maximum RM1,200 monthly per worker (for those earning RM4,000 monthly and below) is not sufficient for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Singapore, in contrast, covers up to 75 per cent of the first S$4,600 of all local workers’ monthly pay for this month, and between 25 per cent and 75 per cent for the next eight months.

The unemployment rate, according to the Malaysian Employers Federation, could skyrocket to 10 per cent or even 15 per cent. Malaysia’s unemployment rate was 3.2 per cent, or 510,000 people, as of last December 31, according to the Department of Statistics.

This means that some middle class Malaysians are in danger of falling into the bottom 40 per cent (B40) category, while other B40 people may plunge into hardcore poverty.

Instead of just dealing with the B40, Malaysia could possibly be facing a B50, with half of the population in need of welfare assistance.

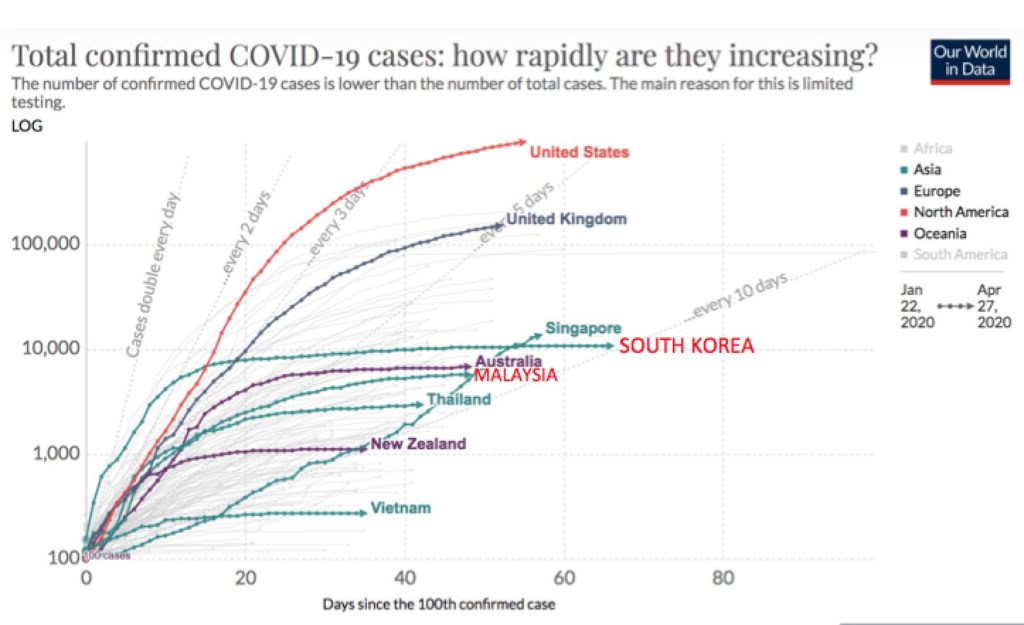

UOB Kay Hian Research has reportedly warned the government about a possible recession, pointing out that the MCO in Malaysia was longer than lockdowns in other countries. Economists reportedly lowered their gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecast for Malaysia this year to -6 per cent, worse than Malaysia’s economic situation during the 2008-09 global financial crisis (1.5 per cent economic growth in 2009), and nearly as bad as the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis (-7.4 per cent growth in 1998). The Malaysian International Chamber of Commerce and Industry reportedly said yesterday that an extended MCO could permanently damage Malaysia’s fiscal health and affect foreign investor confidence, urging the government to reopen the economy now.

Malaysians who lose their income during an economic downturn may not necessarily be able to rely on government welfare aid, as Malaysia, unlike socialist countries in the West, does not have a comprehensive social safety net for the unemployed, due to a small individual taxpayer base. Under the Employment Insurance Scheme (EIS), retrenched workers only receive unemployment benefits of an average of RM1,600 a month for six months of joblessness, as the scheme gives a percentage of one’s salary capped at RM4,000 monthly.

Public health experts, however, support a longer lockdown. Universiti Malaya epidemiologist Dr Nirmala Bhoo Pathy suggested extending the MCO till after Hari Raya on May 24, making the lockdown at least 10 weeks’ long. She cited a study on United States cities during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic that found better health outcomes linked with various safe distancing measures lasting for 10 weeks, like isolation of the sick and quarantine; school closures; and cancelling public gatherings.

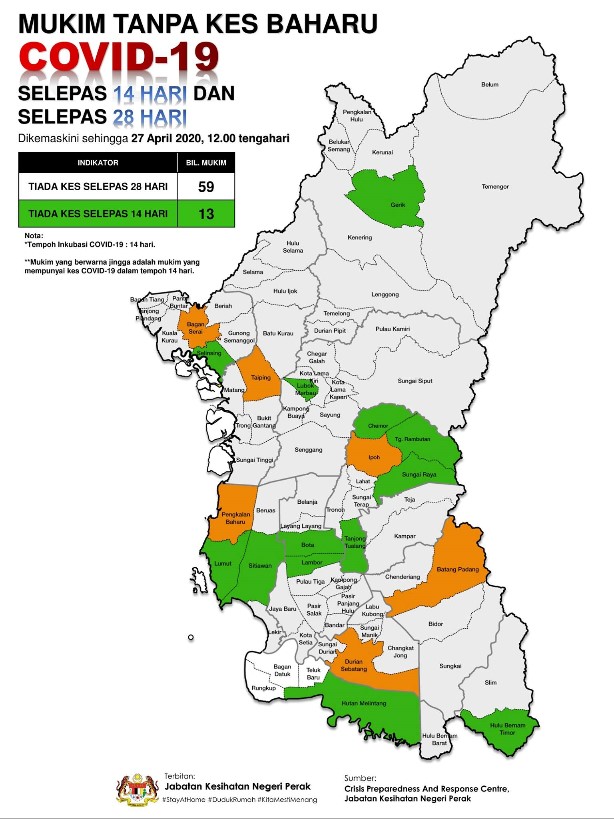

Former Health deputy director-general Dr Lokman Hakim Sulaiman told me that the MCO should only be lifted in areas that have not reported new Covid-19 cases for over 28 days, dubbed as “white” zones, subject to tight border controls. The Perak state health department released a map of new Covid-19 infections in the northern state as of April 27, showing a whopping 59 “white” sub-districts (mukim) without any new cases detected for over 28 days, as well as 13 “green” mukim that did not report new infections for over 14 days. Only six “orange” sub-districts detected new Covid-19 cases within a fortnight. Tracking active infectious cases in districts daily isn’t very useful because all of these cases have been isolated from the community anyway and put in hospital.

I believe that the health and economic costs of a prolonged nationwide MCO in Malaysia — even as European countries and Asean nations like Vietnam have started easing their lockdown measures – may outweigh the benefits of extending authoritarian movement restrictions to after Hari Raya late next month.

First, a recession may physically harm our health. CNN reported a 2018 study that found the United States’ Great Recession in the late 2000s was linked to significant increases in blood pressure and blood glucose levels, as people were stressed by different things. Among those who got physically ill because of the recession were younger adults who needed jobs and older homeowners who lost their property investments as home values plunged.

There is a significant number of Malaysians with high blood pressure and diabetes. Five years ago, an estimated 17.5 per cent of the adult population in Malaysia had diabetes. Close to a third suffered from hypertension. Almost half of Malaysian adults are overweight or obese. If the rising trend of such non-communicable diseases continued from 2015, we would only expect to see more Malaysians with diabetes and high blood pressure this year.

Medical professionals have warned the government about potentially higher death rates among people with cancer and diabetes, amid a delay in hospital treatment, missed appointments, and medicine supplies running out during the lockdown that could lead to complications. Former Health director-general Dr Ismail Merican noted that most non-Covid-19 hospitals in both the public and private sector in the Klang Valley have stopped all elective surgeries, as he stressed that cancer surgeries must continue because these shouldn’t be considered “elective” operations for life-threatening diseases.

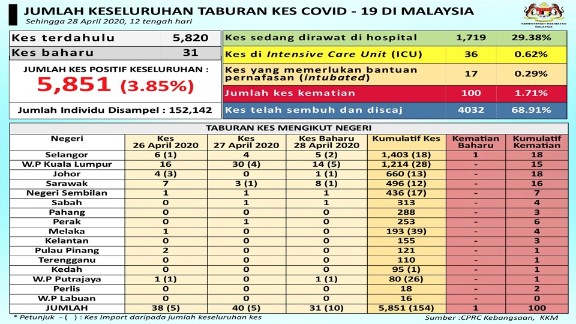

The mortality rate for Covid-19 in Malaysia is only 1.7 per cent. The Ministry of Health (MOH) estimates that 80 per cent of people infected with coronavirus only suffer mild symptoms, like the flu. A hundred people in Malaysia have succumbed to Covid-19 as of yesterday, since the epidemic broke out here three months ago last January.

Compare that to cancer. Cancer deaths in Malaysia rose by nearly 30 percentage points in 2012-2016, compared to 2007-2011. Malaysia recorded 82,601 deaths from cancer in the 2012-2016 period, with 2016 seeing close to 19,000 fatalities, or an average of 4,700 cancer deaths every quarter that year.

Higher cancer mortality is linked to late detection of the disease. Malaysia reported an increase of about five percentage points in cancers detected in the late stages, from 58.8 per cent of cases in 2007-2011, to 63.7 per cent of cases in 2012-2016.

Of course, cancer is not a contagious disease, unlike Covid-19. But severe public health measures bordering on war-like actions – with armed soldiers, barbed wires in the city, and police checkpoints – will further deter women from getting a potentially life-saving check-up if they spot a lump in their breast.

Even before the Covid-19 crisis hit, Malaysians were generally apathetic about regular health screenings, much less now during the lockdown with literal roadblocks. How many Malaysians have skipped mammograms or pap smears at their regular clinics because of the MCO? How many Malaysians risk their cancer progressing to the next stage amid a backlog of cases in both government and private hospitals caused by the lockdown?

How many parents have stopped bringing their babies for immunisation during the MCO? Malaysia has faced a resurgence of extremely contagious vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, whooping cough, and diphtheria since 2018. Then there is the problem of highly infectious polio in Sabah.

The R0 (pronounced R-naught) for the coronavirus is about 2 to 2.5, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), which means it’s less contagious than measles with an R0 ranging from 3.7 to 203. A Malaysian based in Petaling Jaya tweeted that his baby, currently in Ipoh with grandparents, has missed two vaccine shots scheduled at a Kelana Jaya clinic, as police rejected his application for him and his wife to bring their child back from Ipoh.

Even if ministers say that travelling for health care purposes is permitted, their ruling may not necessarily go down to the ground because authorities are treating the Covid-19 epidemic like a national security issue, rather than a health problem. Health care requires trust in medical professionals, hence people generally prefer to see their regular doctor rather than go to a random clinic or hospital nearby. The police and Armed Forces do not understand this (nor are they expected to, because they’re not health professionals).

People must be able to access health care in the easiest way possible.

If even people who want to get screenings or vaccination for their children are hindered from doing so, what more people who are already reluctant about such matters? With authorities jailing or fining people for infractions of the MCO, Malaysians are understandably afraid of breaking the lockdown, even if it’s for a valid medical reason.

It’s no use telling individuals to just go get screened or vaccinate their children; public health policies must encourage such behaviour by removing as many obstacles as possible, be it police roadblocks or requirement of a medical letter.

I believe that the MCO should be completely lifted in neighbourhoods or zones that do not report any new cases for over 14 or 28 days as of May 12. Get rid of police roadblocks within those areas that should remain guarded only against outsiders. Let businesses resume and allow residents to move freely – exercise in the park, walk their dog, go to laundromats – within such residences, while keeping outsiders out and residents in. This strategy may not ensure full opening of businesses, by the way, because workers do not always work in their area of residence.

Remove the Malaysian Armed Forces completely from the enforcement of the MCO from May 13; this is a health crisis, not a war. Police can continue roadblocks at state borders and certain areas in the cities – predominantly in Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, and Sarawak – but stop sending people to jail for breaking the MCO. Adding newly incarcerated people to vulnerable crowded prison populations defeats the very purpose of the lockdown. Interstate travel should continue to be banned during Hari Raya to prevent an exodus of people from hotspots in the central region of the peninsula to other states.

The MCO is not meant to eliminate the Covid-19 epidemic, as Health director-general Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah pointed out. A lockdown is simply aimed at reducing the rate of infection to prevent the health care system from being overwhelmed with a spike of Covid-19 cases in a short period of time — ie: “flattening the curve”.

Inevitably, when the MCO is lifted, coronavirus cases will probably rise – but this is fine as long as our hospitals can manage these patients with sufficient beds and ventilators. As it is, Malaysia has enough beds that we can afford to put everyone who tests positive for Covid-19 in hospital, even if they don’t need treatment because they only display mild or no symptoms, for at least 14 days.

Malaysians, I feel, can self-regulate even if the MCO is lifted during Ramadan. We generally understand the danger of Covid-19 that most of us would continue to maintain safe distancing, avoid large gatherings, and wash our hands more frequently than before. A total of 21,106 people have been arrested as of April 27 for breaching the MCO, or 0.07 per cent of the 32-million population. If that isn’t an impressive compliance rate, I don’t know what is. And for people who are absolutely terrified of the coronavirus, they and their household (ie: people who live with them) can choose to stay home, even if others venture out.

Most businesses must be allowed to reopen on May 13 (see this useful guidance), except in Covid-19 hotspots, so that they can avoid shuttering (and retrenching workers) without relying on government assistance. They will have to adapt to the “new normal” by going digital as much as possible, although it seems that even top government officials haven’t yet shown the way by continuing face-to-face press conferences and a ridiculous one-day Parliament sitting, instead of using video-conferencing platforms.

MOH, as well as other ministries, businesses, and society in general should continue blasting out messages on safe distancing and good hygiene. MOH should also probably move forward to loosening criteria for testing, as Covid-19 tests in private facilities are still very expensive, so that anyone can get tested for free and go to hospital early before their condition deteriorates.

Contact tracing should be improved; the MySejahtera app received many poor reviews in the Google Play Store, as users say that the app shows alerts of cases only in one’s location, instead of other areas. The Gerak app for requesting permission for interstate travel may deter users because of the excessive personal information required, like access to one’s phone camera and memory card.

Finally, the government must reveal its exit strategy for the MCO now, two weeks before May 12, and detail exactly what metrics it is using to end the lockdown so that Malaysians can track progress over the next fortnight. Such plans should be deliberated in an emergency Parliament sitting so that lawmakers can voice any concerns or suggestions, as people’s representatives would know best the conditions of their constituency.

Malaysia’s public health response to Covid-19 must be decentralised because of the infectious nature of the disease – different areas are affected in various degrees. Then we may be able to tackle the epidemic effectively even when the nationwide lockdown is lifted.

Boo Su-Lyn is CodeBlue editor-in-chief. She is a libertarian, or classical liberal, who believes in minimal state intervention in the economy and socio-political issues.