KUALA LUMPUR, April 23 — An anaesthesiologist has described his harrowing experience in an intensive care unit (ICU) with very sick Covid-19 patients who may suddenly die when their condition deteriorates rapidly.

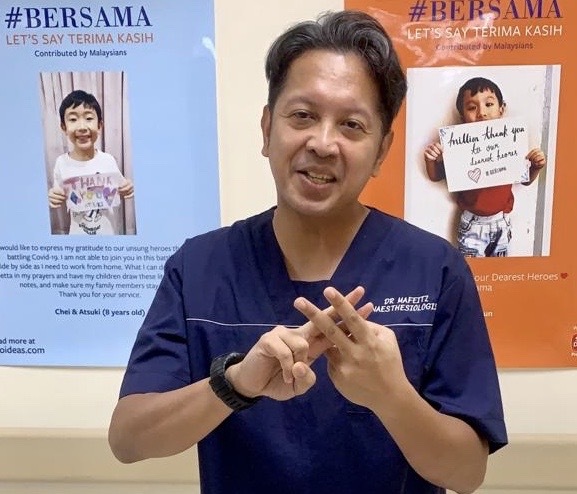

Dr Mafeitzeral Mamat — a Gleneagles Hospital Medini Johor consultant anaesthesiologist with sub-specialty training in cardiothoracic and regional anaesthesia — volunteered his services to the Ministry of Health (MOH) for free from April 6 to 26 to work in the ICU ward at Sungai Buloh Hospital, the designated Covid-19 centre in the Klang Valley.

This is his story, as told to CodeBlue:

I am rostered together with the other MOH anaesthesia & intensive care specialists to cover the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) with different teams. Each team is in charge of a designated ICU wing and is led by an intensivist with a few anaesthesia & intensive care specialists and a number of medical officers.

My job is to take care of the patients in ICU. Patients in ICU are the severely ill Covid-19 patients. These patients are fragile and very sick. Most of them need mechanical ventilation support for their respiratory failure. Besides that, these patients have multi-organ failure, such as kidney failure and heart failure, that needs machine support too.

Every day, we will do our rounds: to examine the patient’s condition, to plan their clinical management, performing ICU procedures like inserting invasive monitoring lines, and anticipating problems that may come.

These patients are monitored very closely as their condition can take the turn for the worse in a blink of an eye.

There are two phases when these Covid-19 patients are severely ill in ICU. The first phase is the infection to the lungs, i.e pneumonia. Once this is managed, the patient may be on their way to oxygenation exchange recovery. However, there is a second stage where we describe it as the cytokine storm. It is when the body reacts via overdriving the body immune system (inflammation) to fight off the viral infection.

This can be overwhelming and be counterproductive as it may lead to multi-organ failure. We have to be careful in managing and administering appropriate drug therapy at the right time. First, to catch them early during the deterioration of the lung. Second, to catch them before the cytokine storm commences. Every patient’s onset is different, hence the tight constant monitoring of their vital signs and biochemical parameters.

The heart or lungs can deteriorate really fast and we need to catch this exact moment to not let that happen and administer appropriate treatment to the best that we can. In a condition called pulmonary embolism, patients can suddenly die. In Covid-19, it occurs more than other diseases. Each body system will be analysed to make sure that the infection can be controlled and not damage other organs.

There are two ways where, despite being on a ventilator, patients with Covid-19 can still die. One, when the patient presents to the hospital at the late stage (Stage 4 and 5 — reference to the MOH classification of Covid patients). At this stage, despite giving enough oxygen, the body may not be able to utilise it as it has reached the point of no return. Two, when the patient is having overwhelming multi-organ failure despite full support, i.e. kidney, liver or heart failure, where even though with good oxygen supply delivered, the body continues to fail.

There is also pulmonary embolism, where there is a blood clot that jams up the lungs, the gas exchange mechanism, hence the inability of the lungs to exchange supplied oxygen to the body. This seems to happen frequently in Covid-19 patients as they can be hypercoagulable (abnormally higher tendency towards blood clotting). When this happens, patients will suddenly present to us with poor oxygenation, despite maximum oxygen therapy, and depending on how bad it is, the patient can immediately die even though they were perfectly stable moments ago.

Based on what we have seen, Covid patients can deteriorate very fast.

The patient may be admitted to the hospital at Stage 2 with mild symptoms and appear to be not too bad in the morning. However, in the afternoon, he deteriorates markedly. He will be breathing heavily despite the increasing oxygen therapy given (from nasal prong oxygen to high-flow mask oxygen). Respiratory rate more than 40, with really putting in an effort to breathe whilst sitting up in hunger of oxygen.

When the patient starts to be restless, it is a sign where there is a lack of oxygen delivery to the brain. He can be incoherent and unable to contain himself to settle down: “I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe!” This is when we know he urgently needs mechanical ventilation support before the lungs totally fail him.

These patients are usually referred to us in the ward when they start to develop shortness of breath. We will examine them and with reference to appropriate blood results like ABG (Arterial Blood Gas), we may decide to ventilate them early rather than wait for them to deteriorate. It is about catching those deteriorating at the right time for a higher chance of good outcome.

Covid patients will be on a ventilator for more than one week. In my centre, as per the common statistics of this pandemic around the world, most are those aged 60 and above, with multiple comorbids like hypertension and diabetes. It is because of these comorbids too that it becomes very complicated in managing these patients in ICU.

Patients may recover well from their initial Covid pneumonia and extubated (removal of tube from the throat that helps one breathe). However, their body can be very weak and they are very susceptible to hospital-acquired infections and a number of patients need to be reintubated because of septicaemia (serious bloodstream infection). These are the reasons for their prolonged stay in the ICU. There are a few patients who repeatedly get septicaemia and have cycles of reintubation and treatment.

There are patients whose initial Covid pneumonia had damaged their lungs badly. After extubation, the lung function seemed not to normalise as to how it was before.

When visualised via CT scan, we discovered that there is only little left of what a normal lung should look like.

They may need long-term home oxygen therapy.

When the patients are on ventilator, we have to comatose them with our medication so that their body can mechanically and chemically supported to stabilise them. Having a tube in the throat can be very painful and unpleasant. Once the initial insult is under control, we will slowly taper down our sedation. In simple words, initially we will take over their breathing and organ support and as the patients recover, we will let their body take charge again of its own function.

Once they are on the way to recovery, we will minimise our sedation and wean down the ventilation support. We will communicate with them and assess their suitability for extubation. We will ask them about their wellbeing and those who are recovering well can even communicate via writing on a piece of paper as they can’t talk due to the tube in their throat! The patients themselves will indicate whether they are ready to be extubated.

It’s always good to get a thumbs-up reply from them when asked whether they are ready to be off the ventilator!

Every day at noon after settling our rounds, we will call the next-of-kin to inform updates regarding the patient’s condition. During this Covid-19 pandemic, we are the only contact for the family members. We will spend some time on the phone as family members are always eager to know what is going on with their loved ones.

It is of mixed emotions in handling every query, anxiety, sadness and we have to be compassionate whilst communicating. Some of us do get overwhelmed on one phone call and cannot continue to do the rest. It can be rewarding when we are to deliver good recovery news, but it can be really demotivating when we are to inform deterioration and bad news to those who are themselves full of emotions on the other side.

What makes the big difference in managing Covid-19 patients in ICU would be the total no direct contact of patients with their family members. In the normal ICU, family members are allowed to visit, within restricted hours, the ventilated patients (with ICU dresscode precautions). We will organise family conferences to update the management plan of the patient.

Unfortunately, in Covid-19, there is no way the next-of-kin are allowed to be near the patient at any time.

The saddest part would be that none are allowed to be with the patient on their deathbed, nor to see their faces for the last time before burial or cremation.

Preparing For The Danger Zone

In normal intubation procedures, we get close to a patient’s face, inches away, to insert a tube down the airway so that we can put the patient on a ventilator. That was the norm before Covid. That was how we were trained for intubation.

When Covid came into the picture by mid-January, we were all warned of the possibility of getting infected while intubating. Hence, with all Covid and suspected patients, we will don our PPE (personal protective equipment) and use a headbox or a transparent plastic sheet cover and, if possible, together with a video laryngoscope which helps us to distance away from the patients.

Patients may cough or gag when we’re intubating them, but I wouldn’t say I’m scared because that’s why we chose anaesthesia and intensive care! This is our line of work.

It’s the worry of the unknown, especially with Covid-19, the worry of getting our loved ones infected and affected badly if we accidentally get ourselves infected in the line of duty. Most of our ICU patients themselves are not the index patient, but the first to fifth generation.

That’s why it’s strictly powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) suits when doing procedures like intubating. Otherwise, when seeing them at other times, we would be on Level 3 PPE.

We work closely with the infectious disease team in deciding what is the best treatment for the patient. Patients who are admitted to ICU have other comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac disease. Covid-19 infection can worsen the diseases, hence their long road to recovery with prolonged stay in ICU.

Donning and doffing the PPE is very important and we were briefed and trained strictly on our first day here before we were allowed to enter the ICU.

For aerosol-generating procedures (AGP) like intubation and extubation of patients, we need to be donned at the highest level of protection. Hospital Sungai Buloh is well-equipped with PAPR suits. For AGP procedures like intubation and extubation, the specialists will take the lead because it needs to be performed by an experienced expert and done with most care, as the risk is high for both the patient and the doctor.

Work Burden

We work in eight-hour shifts. I do oncalls too, oncall meaning to be in the hospital for 24 hours. Every day, there will be an oncall team for each ICU unit. My oncall in Hospital Sungai Buloh ICU is one to two per week.

There is an operating theatre on standby if patients who are Covid-19 positive may need urgent life-saving surgeries. As an anaesthetist, we are to handle this as well.

The Head Of Department of the Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Unit planned his manpower well in preparing the hospital as a Covid-19 centre since late February.

Hence, we were able to work on single shifts each and not do too many calls.

This applies to the ICU medical officers too.

Rest is adequate because of this as it is very exhausting after each shift — physically because of the long hours of strict PPE gowning (once we are in the ICU fully donned up, we will stay there until the end of our shift. Hence, we will ensure that we have had our food and drink adequately beforehand and, of course, toilet!). The shift can be mentally draining too because of the stress in managing high-risk patients.

Joining Sungai Buloh Hospital

Hospital Sungai Buloh was designated as the Klang Valley centre for Covid-19. MOH anticipated the cases would spike in mid-April after the sudden surge of Covid-19 patients in March.

The ICU was expanded from its normal capacity of 35 ICU beds into 60 ICU beds (Hospital Sungai Buloh was planned to provide 100 ICU beds if it needs too). The Burns High Dependency Unit and Cardiac Care Unit were turned into ICU beds fully equipped with a ventilator for each bed. At this point, obviously, there was a lack of manpower to cope with the emergency expansion.

MOH have mobilised their doctors and nurses to Sungai Buloh. However, other MOH Klang Valley hospitals could not fulfill the capacity required by Hospital Sungai Buloh because the public hospitals are busy themselves with the ongoing non-Covid hospitals.

In early March, the Health Director-General himself asked for doctors (specifically for intensivists and anaesthesiologists) in the private sector to volunteer and help MOH hospitals. There was also an SOS email by the MMA (Malaysia Medical Association) and MSA (Malaysian Society of Anaesthesiologists) pleading for volunteers.

I then registered myself in the link provided by MOH. Later, the MSA organised and sorted the paperwork with the MOH in allowing us to join the MOH ICU unit. There are a total of four anaesthetists from the private sector who joined Sungai Buloh.

As for my background, I have been volunteering for medical disaster relief missions overseas with Mercy Malaysia and Aman Palestin since 2013. I am also a member of a new NGO registered with the ROS (Registrar of Societies) called MedicAid, together with my few friends who are doctors.

If it was not for the Covid-19 pandemic, I would have been on a medical mission for MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières, an international medical relief organisation) in April 2020. This did not happen for obvious reasons.

Since I have planned for my leave anyway and it comes to a situation where I can offer my expertise to help my own country in need, why not?

Before joining the private sector in 2015, I was with UiTM (Universiti Teknologi MARA) and had worked in Hospital Sungai Buloh before. Hence, I am fairly familiar with the place and people here. It would be nice to return and link up with my former colleagues.

Adequate manpower is very important in our line of work as with numbers, we can reduce the stress, fatigue, and the burden of hours.