KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 14 — Distributor Zuellig Pharma Malaysia will absorb Eli Lilly and Company Malaysia’s staff and assume control of the pharmaceutical giant’s sales and marketing here next month.

CodeBlue understands that from November 1, Zuellig Pharma will hold the rights to sell, promote and distribute Lilly’s current and new products in Malaysia, while the pharmaceutical distributor’s commercial solutions business unit will take charge of the sales and marketing of the American drug manufacturer’s products here.

A “significant” number of Lilly Malaysia employees are also expected to move into Zuellig Pharma from that date, according to an internal Zuellig Pharma circular sighted by CodeBlue about the “strategic partnership” between both companies.

“Lilly has entered a partnership in Malaysia with Zuellig Pharma, effective November 1, 2019, to better serve patients across the country.

“Lilly remains committed to ensuring patients’ access to medicines, therefore currently registered medicines and future innovations will continue to be available in Malaysia through Zuellig,” Lilly said in a statement last Saturday, when CodeBlue contacted Lilly’s global headquarters in Indiana, the United States.

Lilly country manager (Malaysia and Singapore) Adrian Wong simply told CodeBlue: “For now, I confirm the Eli Lilly and Company Malaysia will remain in operation and we have no intention of closing down anytime soon.

“However, we are embarking into a new business model of operation and partnership which we believe will further strengthen Lilly presence in Malaysia and in the region.”

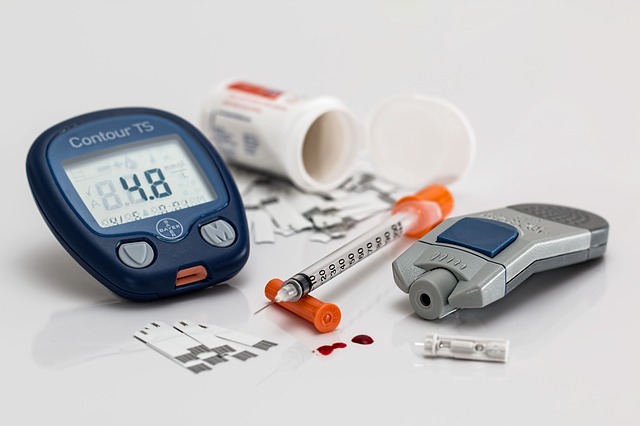

Lilly — the maker of popular diabetes treatment Humalog (insulin lispro) and antidepressant Prozac (fluoxetine) — has provided Malaysia innovative drugs in diabetes, oncology, osteoporosis, and central nervous system since the establishment of its office here 40 years ago in 1979.

Peilynn Cheong, managing director of IPH Pharmaceuticals, a small wholesale pharmaceutical company, said even though Lilly termed the move as a “strategic partnership” with Zuellig Pharma, the US drug manufacturer was essentially exiting the Malaysia market.

“Basically, they have decided to close,” Cheong told CodeBlue.

More MNCs Leaving Malaysia?

The health care consultant also personally predicted that more pharmaceutical multinational corporations (MNCs) may pull out of Malaysia, especially smaller companies.

“The Malaysian economy is going downhill. Government is not purchasing any of the MNCs’ [products] already. This means 60 per cent of the market is gone in terms of volume.

“Left is the 40 per cent, which is the M40 (middle 40 per cent) contributing, and M40 is feeling the squeeze of the economy and they’re skimming on their health. MNCs’ sales have been dropping tremendously over the last few years.”

Cheong claimed that Lilly hasn’t been able to sell much of its huge-market products in Malaysia due to their expensive prices. The government, she said, mostly buys generics.

“So because of that, sales have shrunk in Malaysia over the years,” said Cheong. “At a corporation, ROI is a must.”

Cheong, who previously worked in both local and multinational pharmaceutical companies, said human resources was among the biggest costs in a drug maker’s local affiliate.

“So, closing down the office actually eliminates all these expenses. Yet they still will be able to get a profit, a pretty good profit because when they sell their product to Zuellig, they have already got nett, without coming up with a single sen in Malaysia.”

Peilynn Cheong, IPH Pharmaceuticals managing director

Drug Prices May Rise

As such, she said, medicine prices can go up because when a drug maker outsources its products to a distributor, as opposed to selling them from a local office, the selling price to the distributor would have been marked up to include the manufacturer’s profit. The distributor then will impose its own mark-up on this higher manufacturer price to cover expenses on staff, registration licensing, warehouse, distribution, and rental, among others.

“So, the selling price to us actually increased,” said Cheong, who runs a wholesale pharmacy arm for private medical practitioners.

“Every time the principal outsources the product to distributor, the price will actually go up. When they outsource, they already earn. Now instead of one company profiting, there’s two companies that need to profit — one is the principal company and the other is Zuellig Pharma.”

The absence of a local office, Cheong said, leads to less investment coming into the country. Many MNC drug makers have been outsourcing their products in Malaysia, especially old ones, to distributors over the years.

Lilly previously ran clinical trials on Prozac and antipsychotic Zyprexa (olanzapine) here that Cheong said enabled participation from Malaysian lecturers and universities, as Malaysia is a trial site.

Besides investment in research and development, setting up a local office means that a pharmaceutical MNC also pours in money on office rental, customs tax on product imports, and hires of Malaysian staff.

Cheong said outsourcing products to distributors, however, means that for drug makers, “no sales, no sales lah, every time I sell to you, I already profit.”

Global pharmaceutical manufacturers make decisions to set up local offices based on whether it sees growth potential in a country, such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia or Thailand, as there will be no focus on its products if they are simply left to distributors that manage products by several drug makers.

“If there’s no potential to grow or there’s no potential for them to increase their sales, then this country becomes non-potential to them,” Cheong said.

Compulsory licensing, in which a government allows generics to be produced without consent from the original drug maker, and drug price ceilings are among the factors considered by drug makers on whether to set up shop in a country, besides income, population size, disease incidence and prevalence, and other government policies, according to Cheong.

Pakatan Harapan is considering regulating the prices of innovative medicines, while the previous Barisan Nasional government had used a compulsory licence for the Hepatitis C drug, sofosbuvir.

Cheong noted that global drug maker Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) pulled out from Malaysia more than 10 years ago because the local market was not considered profitable. Over the past three years too, the Malaysian operations of some large pharmaceutical MNCs were merged under another country, abolishing the general manager (GM) position in Malaysia.

AbbVie has merged Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong to be managed by one GM. Sanofi Malaysia’s operations, however, are still managed by a Malaysian leadership team based in Kuala Lumpur, comprising a One Sanofi Country Chair, General Manager Vaccines and a board of directors; Malaysia is part of Sanofi’s cluster of countries including Singapore and Thailand.

“Of course, the GM of the country who wins will always be the country seen as most potential for growth,” Cheong said.

“For those countries that they don’t see as potential, they’ll actually pull out their resources and do a sort of like tai chi and go to those that have more potential.”

Update on October 15 at 2:40pm:

Sanofi Malaysia said in a statement that “with a rich history in Malaysia over 50 years, Sanofi is committed to increasing access to health care and improving the well-being of Malaysia patients.”

Editor’s Note:

CodeBlue incorrectly reported that Sanofi Malaysia’s operations are managed by the Thailand GM based in Hong Kong. Sanofi Malaysia’s operations are actually managed by a Kuala Lumpur-based team. The article has since been corrected.

CodeBlue incorrectly reported that AbbVie Taiwan is merged in the same group with Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong operations under one GM; AbbVie Taiwan operations are actually managed by another GM. The article has since been corrected.