Last Saturday, I suffered excruciating stomach cramps that I’d never experienced before in my life. So I went to a quiet and peaceful emergency room (ER) at a medium-sized private hospital just five minutes away from home later that day.

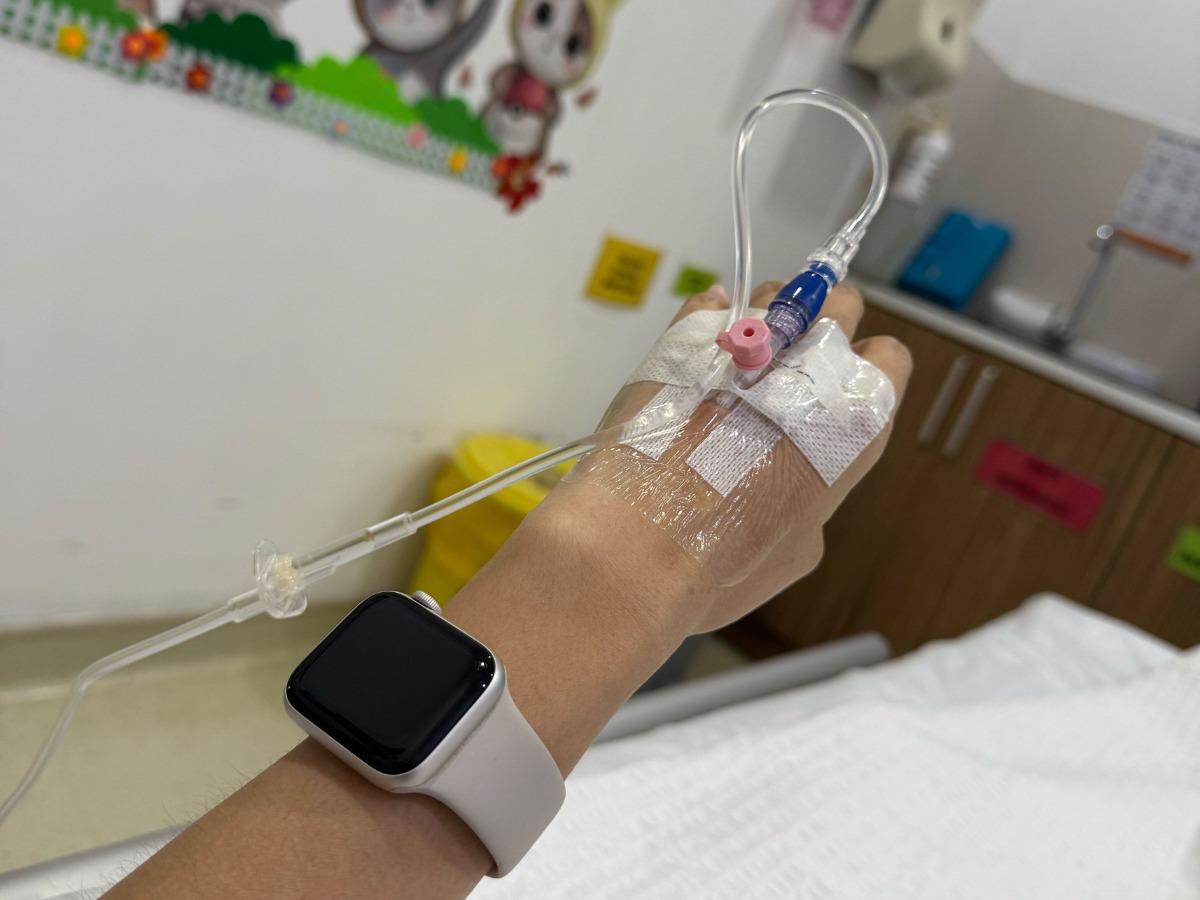

A medical officer put me on an IV drip in the Yellow Zone and immediately ordered a blood test; the results, which came in an hour, were normal. He asked me if I wanted to be admitted prior to possibly doing a CT scan the next day to find out what the problem was.

I foolishly declined since I didn’t have cramps while I was medicated on IV and I figured I would be fine taking medicines at home (big mistake, huge!) I didn’t see the point of lying on a hospital bed when I could continue working. So we made an appointment for me to see a specialist on February 4.

The stomach cramps returned with a vengeance after I went back home, to the extent of disrupting my sleep at night. I was already regretting my decision not to be admitted.

But throughout the last few days, my symptoms eventually subsided as I took gastric medication.

When I went to see a general surgeon yesterday, he ordered an ultrasound, which showed normal results. So he suggested either a breath test or endoscopy to check for H. pylori infection. I decided on the former and he agreed since this was my first episode, even though a procedure would be more accurate.

(To be honest, the mention of “endoscopy” freaked me out. I’ve never undergone any procedure before. Yes I report on health care all the time, but those are mostly policy issues and it’s very different when you’re a patient).

My stomach cramps coincided with my period, but my doctor seemed annoyed when I cited ChatGPT’s possible diagnosis of menstrual prostaglandin-driven intestinal spasm, not gastritis (I fed AI my symptoms, bloodwork, and the list of medicines I was on).

“If you want, I can help you phrase this clearly to a doctor so it’s not dismissed,” ChatGPT told me – not so helpfully. “You read your body correctly – and the meds confirmed it.”

But I defer to a doctor’s medical authority, not AI. So we made an appointment in a week for the results of my urea breath test.

I have spent about RM1,500 out of pocket so far for my two hospital visits, excluding my future specialist appointment, including these costs:

- Urea breath test: RM310

- Blood test: RM295

- Medicines: RM216.30

- Surgeon’s consultation fee: RM200

- Procedure (triaging, ER nursing procedure, IV injection, blood taking, IV insertion): RM190

- Ultrasound: RM165

This medical episode won’t bankrupt me, but it’s not cheap.

In a rebuttal to the Association of Private Hospitals Malaysia (APHM), four specialist doctors insisted that the health insurance “buffet table syndrome” was real.

Dr Rajeentheran Suntheralingam, Dr Musa Mohd Nordin, Dr Ahmad Faizal Mohd Perdaus, and Dr Sng Kim Hock claim that private hospital ERs are frequently used for non-urgent conditions and that patients often insist on clinically unnecessary admission after investigations, “driven by the desire to claim from their insurance”.

I recently touted my medical plan with near RM1.4 million annual limit as a superior product to the government-designed Base Medical and Health Insurance/Takaful (MHIT) Plan with an RM100,000 annual limit, as my plan is a little more expensive than the Base MHIT but has much higher coverage and benefits.

I didn’t bother getting admitted to try to claim from my health insurance, even though I feel that ethically, my insurer should cover my latest episode (like conventional products in the market, my medical plan requires hospitalisation for coverage of tests).

I have been paying for my medical plan for about five years at about RM2,000 annually. That means I would have forked out some RM10,000 in premiums to date – far higher than the RM1,500 I’ve paid out of pocket so far for my two hospital visits.

I’ve never claimed from my insurance prior to this, except RM300 every two years for health screening/ vaccination benefits. The last time I went to a hospital was more than a decade ago for a dislocated knee cap (emergency at a government hospital).

Not to mention that I bought my policy with the legal promise of more than a million ringgit coverage – every year. What’s a few thousand ringgit in the grand scheme of things?

Diagnostics aren’t cheap. I’ve undergone a blood test and ultrasound, but my doctor still hasn’t confirmed a diagnosis beyond probable gastritis. He even said my breath test may yield false results, so I guess we’ll see whether he recommends an endoscopy during our next appointment.

Health care is like detective work, but I have to pay for the investigation every step of the way.

It’s not like my doctor can skip a breath test or endoscopy and straight away prescribe me antibiotics for a potential but unconfirmed infection. Not knowing the exact cause of my problem niggles at me, even though my symptoms have disappeared.

If my breath test also shows negative results, what does my insurer expect me to do? Skip a procedure that would definitively diagnose my problem and wait for a possible lurking infection in my body to trigger another episode of agonising stomach cramps in future like a ticking time bomb?

I would have to endure intense pain and undergo the same arduous health care process all over again. And yes, I consider my experience arduous because I dislike taking time off work to go to the hospital multiple times. Even if I were to pay out of pocket again, utilisation (and costs) of health care would still increase, simply because insurers refuse to pay to prevent a foreseeable medical issue.

Or is it only considered “over-utilisation” if the payment method changes from self-pay to insurance?

I suppose that I’m the ideal policyholder — someone who pays premiums regularly, year after year, without ever claiming despite experiencing an acute (and, to me, serious) bout of illness.

I didn’t go to the hospital just so I could use my insurance (which I didn’t). I never asked to fall sick. And I reckon that many other patients who did get admitted, and correctly and ethically tapped on their insurance, had genuine health care needs.

While I can afford to pay a few thousand ringgit out of pocket now, I may not be able to do so when I’m retired and hence, will likely go to a government hospital and probably get stranded in the emergency department for a few days before getting warded.

Doctors should not blame patients for failures of the health insurance system in Malaysia. Supporting the government’s Reset strategy – while simultaneously demanding an exemption of doctors’ professional fees from Reset and the diagnosis-related groups (DRG) payment system – also demonstrates a curious lack of self-awareness.

You can’t have your cake and eat it too.

Boo Su-Lyn is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of CodeBlue.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.