Over the past few weeks, there have been many discussions on the announcement by Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad that the government is considering expanding private wings in public hospitals to generate revenue for the underfunded public health care system.

This new health financing reform is about diversifying sources and delivering better value for every RM1 spent, which requires creativity and innovation. According to the minister, the RM1/ RM5 fee at point of care stays, but the new RakanKKM scheme is aimed at developing new sources of revenue with investments from the Ministry of Health’s (MOH) partners.

This will continue to protect and preserve the existing low costs of public health care. The new health care financing reform will be announced in the upcoming Budget 2025 on October 18, 2024.

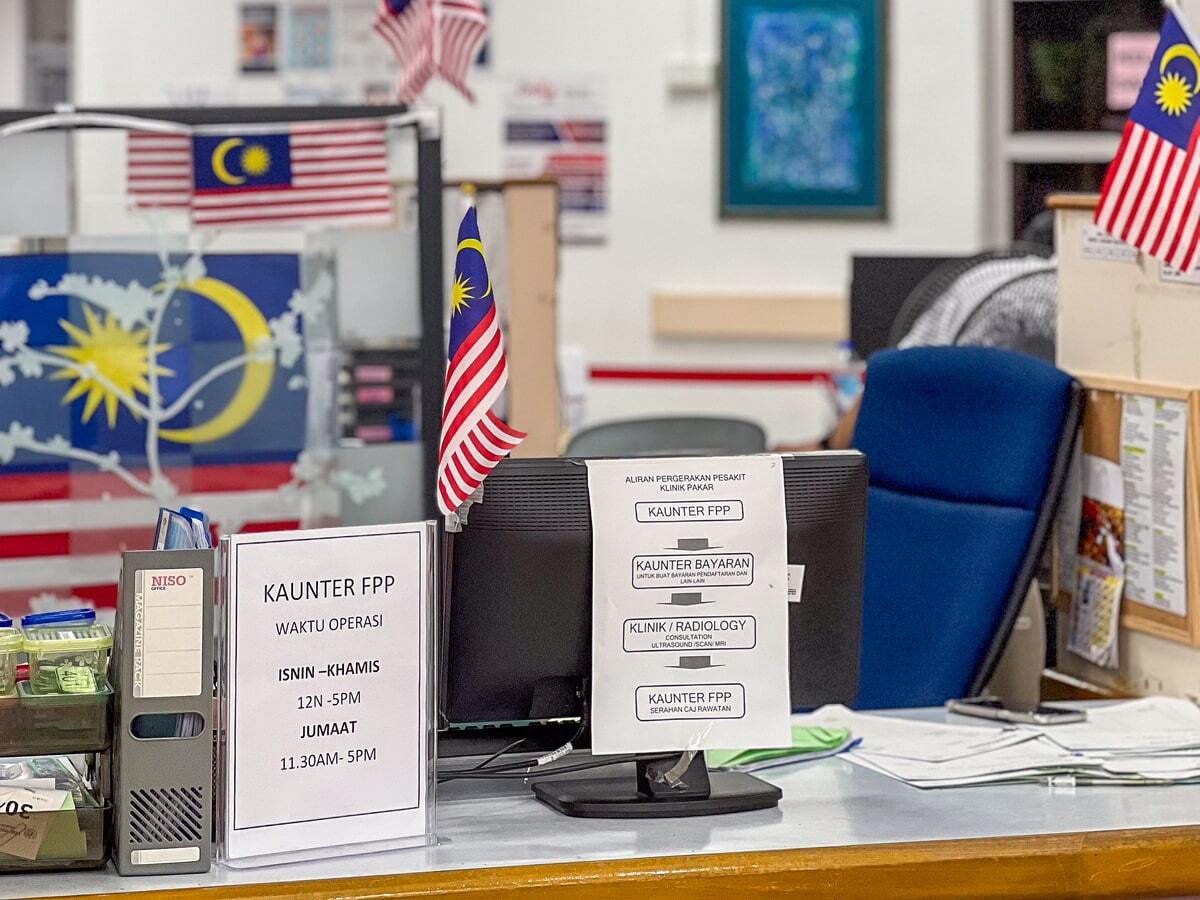

The development of the full-paying patient (FPP) scheme and its implementation in 2007 started with a study of private practice among doctors in public institutions conducted by the Institute of Public Health in 2001.

In 2002, the Ministry of Education proposed that specialists in university hospitals be allowed to engage in limited private practice after office hours. At the time, there were concerns over the resignations of specialists at associate professor and lecturer level from the medical faculties of Universiti Malaya (UM) and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM).

In the MOH, the resignations of specialists in 2003 and 2004 were about 5.1 per cent and 5.3 per cent of the total number of specialists, and reached its peak in 2005 at 6.8 per cent, according to the MOH’s Human Resources Division.

The resignations were mainly of newly qualified or middle level specialists. In Budget 2004, the then-Prime Minister/ Finance Minister said that the government could not provide high remunerations for the specialists and therefore has agreed to set up private commercial wings in government hospitals to enable serving doctors to enjoy better remunerations and thereby continue to serve with the government.

The then-Health Minister requested the MOH to come up with detailed proposals for the implementation of private wings after the Budget announcement. I was then in the MOH, and with my colleague, Fabian Bigar and others, were involved in this proposal.

We visited both the private wings in UM and UKM and witnessed the implementation of the private wings. In 2004, both had separate private wing floors within the same main hospital building.

We met and sought out views from the main internal and external stakeholders, and the proposals were the establishment of private wings, private patients, and locum. In July 2004, the proposal of having private patients in government hospitals, which was later renamed as the FPP scheme, was agreed upon.

The main reasons for the establishment of the FPP scheme was to supplement the income of the specialists and thereby retain them to serve in the public service.

Other reasons include to allow public hospitals to continue to provide quality services, but with competitive prices. It will also help to improve the image of public hospitals, which can be regarded as a step towards the restructuring of the public health delivery system.

The FPP can also help to relieve the government’s share of the health budget by letting those who can afford to pay for their own bills when utilising public hospitals. It has minimal budget, financial, and human resource implications, as it will be using existing facilities and personnel compared to developing new private wings.

Having private wings in public hospitals was not agreed upon because the MOH did not want to be seen as treating patients at two different levels, according to the ability to pay.

Initially, the MOH was considering whether to consider all first class patients as FPP, but later, it was decided to allow patients to choose.

Patients are allowed to choose their specialists and will be assured of the same specialist for any follow-ups. In order not to disrupt normal hours of operations, it was agreed that the FPP will only be operational after office hours and during weekends.

The other principles (adapted from the British National Health Service’s management of private practice from 2003) included that the FPP scheme should not significantly be prejudiced against other patients.

Subject to clinical considerations, earlier consultations should not lead to earlier admission or earlier access to diagnostic procedures. A common waiting list should be used for urgent and seriously ill patients, and for highly specialised diagnostic procedures. After admission, access by all patients to diagnostic and treatment facilities should be governed by clinical consideration.

Standards of clinical care and services provided by the hospital should be the same for all patients.

The FPP scheme was to be implemented gradually, starting with Putrajaya and Selayang Hospitals. It was to be extended to other major hospitals eventually, and later to all hospitals with specialist services. Locum will also be allowed in public hospitals without specialist services.

On July 16, 2007, the Fees (Medical) Full Paying Patient Order 2007 was gazetted and went into operation on May 2, 2007. Full paying patient service means a service offered by any medical institution to any person with the following privileges:

- An option to be treated by any specialist of choice.

- Executive or first-class facilities and services, subject to the availability of specialists, facilities, and services.

The MOH secretary-general may remit a part or the whole of any or all the fees imposed under this Order. With this, the fees collected from the FPP scheme can be shared with participating specialists and the government.

The share collected is not retained by the MOH but will come under the government’s consolidated fund. The FPP Fee Schedule was set based on the Medical Fee Order 1982, the Malaysian Medical Association (MMA) Fourth Edition Schedule of Fees, and the Thirteenth Schedule of the Private Health Facilities and Services (private hospitals and other private health care facilities) Regulations 2006 fee schedule, with input from medical specialists and pharmacists.

In April 2015, a detailed guideline for the implementation of FPP was issued by the Health director-general, known as “Garis Panduan Pelaksaan Perintah Fi (Perubatan) (Pesakit Bayar Penuh) 2007“, to be used in public hospitals.

This guideline provided implementation, monitoring, regulations, and governance structures, to be implemented by participating hospitals and specialists. There was a cap placed on the amount of income that a specialist could earn in a month from the FPP scheme, which should not be more than three times their monthly salary and allowances.

When the FPP policy was discussed initially, one major concern was that support staff might not receive any portion of the fees collected, and this may hamper the implementation. Instead, it was decided that they will be paid overtime fees, and any other perks as prescribed in the General Orders.

This practice is also in line with the practice in the private wings of universities and practices in the private sector.

The fees collected through the FFP are shared with the MOH and participating specialists, as shown in the table below:

The amount of revenue collected from the FPP scheme in 2008 was RM702,000, and increased to RM3.642 million when more specialists came aboard to join the scheme in the two pioneer hospitals.

The amount increased to RM14.098 million when it was expanded to eight hospitals in 2015 as reported by the MOH’s medical development division. In the 2019 annual report, the total amount of revenue collected from the medical fees was RM414.4 million or 57 per cent of the total revenue.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, it was RM417.9 million or 50.2 per cent of its revenue in 2022. How much of this came from the FPP scheme remains unknown.

The percentage of total specialists from public hospitals who resigned when the scheme was first implemented in 2007 was 2.4 per cent, and the rate was about 2.3 to 3.9 per cent in 2016, with a peak of 4.2 per cent in 2011, as reported by the MOH.

Since its implementation in 2007, there has been a noticeable dearth of studies or reviews of the scheme’s implementation (only two were published). In addition, there was a National Audit Department audit of the scheme in 2017.

Before the FPP can be turned into a private wings scheme, the MOH should publish a comprehensive review of the FPP scheme to inform the public whether it has met its main objective of retaining specialists in public hospitals.

It has never been the intention of the FPP scheme to be a new financing scheme within the public health care service as the revenue derived in its present form will not be able to cover increasing demands.

Instead, the government should be grateful that a sizeable portion of its citizens are opting for private health care and paying out of pocket to access these services.

The government should find alternative methods of financing public health care rather than compete with private health care for patients. After all, it is already present within private health care, with Khazanah and state governments owning private hospitals and clinics.

The government should make it more appealing for those who can afford to pay to seek treatment in private health care services, rather than at public facilities. This will reduce the workload in public facilities and make it easy for private specialists to work in public facilities and share resources and facilities, rather than directly competing with them.

The MOH should also analyse the costs and efficiency of its operations in public hospitals and clinics.

In conclusion, in Budget 2025, the government should invest wisely in order to create an enduring and sustainable health care system for all Malaysians.

Chua Hong Teck is an independent public policy and health analyst.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.