KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 18 — The expansion of private wings in government hospitals may trigger the resignations of junior specialists excluded from working there with higher earnings, a health economist said.

Prof Dr Sharifa Ezat Wan Puteh – a professor in health economics, hospital, and health management from the Faculty of Medicine at UKM – observed that both the full-paying patient (FPP) service in a few Ministry of Health (MOH) hospitals and private wings in university hospitals are often monopolised by certain senior consultants.

“Some of these private services are being controlled by a certain number of doctors, certain seniors, and certain clinicians or surgeons,” Dr Sharifa told BFM’s Health & Living podcast, hosted by producer Tee Shiao Eek and co-hosted with Galen Centre Health and Social Policy chief executive Azrul Mohd Khalib.

“They control the area, meaning it’s just them running the clinics and making money. That creates a lot of dissatisfaction among other doctors,” she added in the podcast aired last October 10.

Citing a study she previously conducted on staff attrition in teaching hospitals, Dr Sharifa said she found that the doctors who tended to quit were those who were not involved in the private wings.

“There are two groups: one which has all these perks that they’re able to control or which manages the private sector. The other group comprises doctors who are just doing regular jobs; even though they’re specialists, they might not be doing the private wing,” said the researcher.

“There are a lot of doctors that do that because they just cannot compete with the doctors who are the seniors or the ones already controlling the private wing. These are the ones that leave.”

Federation of Private Medical Practitioners’ Associations Malaysia (FPMPAM) president Dr Shanmuganathan Ganeson previously warned the MOH that just like in teaching hospitals, “cartels” of senior specialists may monopolise the expansion of private wings in MOH hospitals under a new programme called Rakan KKM.

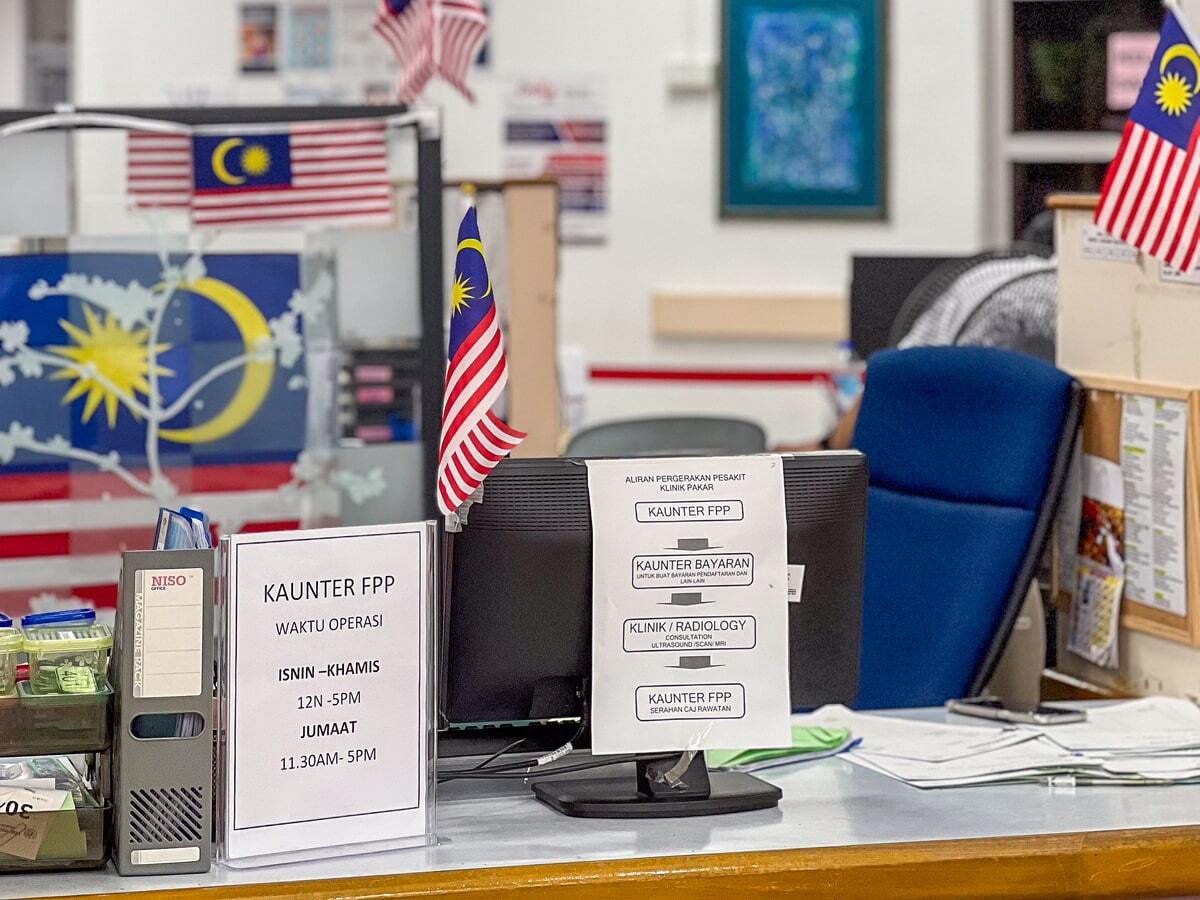

Currently, the MOH provides the FPP service in only about seven hospitals in the Klang Valley, Sabah, and Sarawak, as three other hospitals have ceased the service for years since the Covid-19 pandemic.

Teaching hospitals under the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) run private medical centres alongside their public facilities, including Universiti Malaya (UM) and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM). The private wing of Universiti Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC) is UM Specialist Centre (UMSC), while Hospital Canselor Tuanku Muhriz UKM (HCTM) runs UKM Specialist Centre (UKMSC) as its private wing.

Azrul noted that specialist doctor resignations from the MOH increased by 57 per cent in the past five years from 229 resignations in 2019 to 359 in 2023. A total of 917 specialist doctors quit the public health service in that period.

Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad said last month that the Rakan KKM programme aims to raise revenue for the underfunded health care system and retain specialists in government.

“Not every specialist is offering FPP; obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G) seems to be the majority of FPP services,” Azrul said at the BFM discussion with Tee and Dr Sharifa.

Dr Sharifa – who published a study in November 2023 on MOH’s FPP service in four selected government hospitals between 2017 and 2020 – said surgical and medical procedures are most commonly provided in FPP services due to demand, particularly O&G and cardiology.

“Some specialties are very dormant; they’re not even on the FPP list. So when you look at attrition, it has to be based on whether they’re providing FPP services or not.”

MOH figures in 2022 and 2023 show fewer resignations of specialists in O&G, compared to paediatrics, internal medicine, anaesthesiology, radiology, and orthopaedics that make the top five specialties with resignations. Cardiology isn’t listed.

Tee pointed out that health care services aren’t solely provided by top-tier specialist doctors, as she asked Dr Sharifa how the MOH’s private wing proposal would address remuneration for the allied health care workforce, such as nurses, physiotherapists, and radiographers.

“I think they’re not reimbursed enough, especially if they are shared resources. They might get some extra locum money based on an hourly rate, if they’re working post-working time, but I think they’re not reimbursed enough, especially for allied sciences and labs,” Dr Sharifa replied.

“So that is an area of contention as well. Revenue itself is not everything. Looking down, you have to make sure all this is compensated.”

Azrul pointed out that multiple health ministers have said, time and time again, even before the Covid pandemic, that Malaysia’s public health care system is underfunded, under-served, and overcrowded.

“Yet, suddenly today, we’re speaking as if we have excess capacity in the ability to provide these services. Now we’re even talking about expanding this [FPP] programme beyond what it was originally envisaged,” Azrul said. “Has something changed that enables us to be able to do this?”

Dr Sharifa agreed there are insufficient health care workers in the public sector, saying that the government appears to simply be looking at potential revenue from expanding private wings in public hospitals.

“What we see so far, some of the trends that we’ve looked at, there are profits coming in; it’s a lot. And that actually makes the government excited to look at privatisation of certain services,” she said.

“Again and again, we keep emphasising, whatever is being done, whatever strategy that the government goes ahead with, the most important thing is quality of care. We must make sure that the middle income and lower income are not being sidelined in this strategy.”