KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 30 — Doctors in government hospitals have raised concerns over a plan by the Ministry of Health (MOH) to expand private wings in public hospitals, citing capacity constraints and risks of widening disparities in patient care.

Existing shortages of specialists, support staff, and hospital beds could worsen if more focus is placed on treating fee-paying patients, potentially creating a “dua darjat” (double standards) scenario within the public health system, several medical officers and specialist doctors from the public health service told CodeBlue on condition of anonymity, as civil servants are prohibited from speaking to the media.

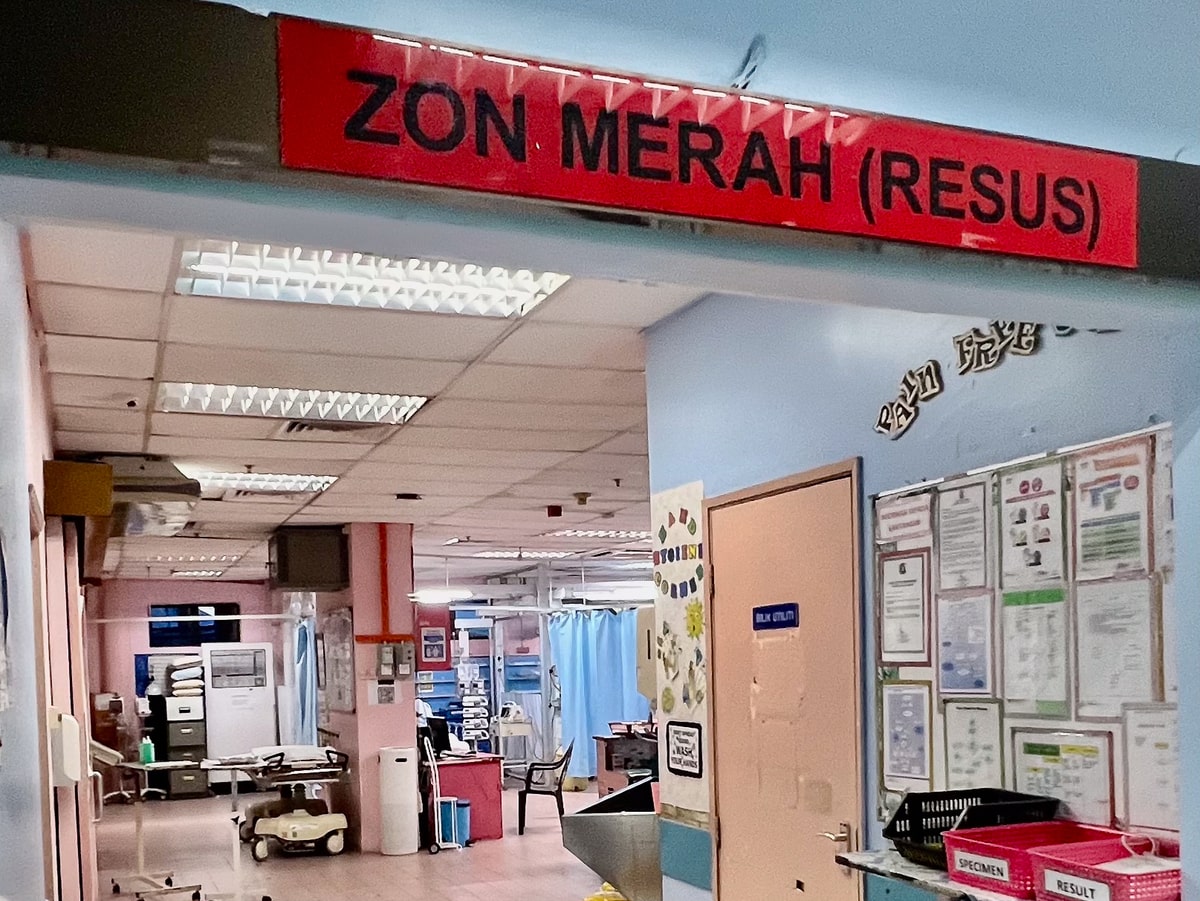

“This is the main issue — most hospitals simply don’t have the capacity. Today, we have nearly 50 patients stranded in the emergency department, waiting for beds. How are we supposed to free up more beds for full-paying patients (FPP)?” said Dr Sam (pseudonym), a specialist at a government hospital in Melaka.

Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad recently spoke about a plan to expand private wings in government hospitals under a programme called RakanKKM.

Details about this proposed programme are scant; it is unclear how RakanKKM will differ from the FPP services currently available in 10 public hospitals under the MOH. The MOH first introduced FPP services in 2007.

Dzulkefly has indicated that government-linked investment companies (GLICs) are investing in a special-purpose vehicle (SPV) for RakanKKM but has deferred further explanations, saying that Malaysians should await Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s announcement.

Dr Alex (pseudonym), an emergency physician at a Klang Valley hospital, is concerned that a dual practice system within a public health care setting – where care is divided based on a patient’s ability to pay – would lead specialists to prioritise profit-generating cases.

This shift could result in longer wait times for those relying on public health care and erode trust in the system.

“MOH is well-known for its ‘antara dua darjat’ (double standards) attitude. They act like the elite and impose many rules for the private sector. Being in one of the five pioneer hospitals in Malaysia, we’ve already seen some abuses of the system.

“Even now, we have patients without beds who are being nursed in the corridors — if there’s even a nurse who has the time to look after them. Unless you have cable (connections) or are a relative of hospital staff, you might not get proper care,” Dr Alex told CodeBlue.

“MOH misrepresents manpower data by presenting all hospital statistics as equal. The population density in Shah Alam is not the same as in Tanjung Karang, yet when discussing bed availability, it is generalised as one. The needs of acute patients are different from those with chronic conditions, yet nursing care is treated as one,” Dr Alex said.

“If this plan goes through, it will be extremely bad because we don’t have the space, staff, and so many other things. To be frank, the Minister can ‘fly a kite’ if he thinks the current MOH team can pull this off. He doesn’t have the team or the expertise at the MOH headquarters to make it work,” Dr Alex added.

Dr Alex described RakanKKM as “merely a rebranding of the old FFP”, given the lack of available information.

The proposal has also drawn criticism from Dr Ming (pseudonym), a former doctor at a public hospital in Seremban, who called the expansion of FPP services a “bad idea,” given that most staff are already overworked.

“First, fix the manpower shortage. Then, start more services. The hospital has no capacity at all (for FPP),” Dr Ming said.

Dr Drew (pseudonym), a doctor in the obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G) department at another Klang Valley hospital, said that while his hospital can currently manage to offer FPP services for O&G, an increase in FPP cases would likely compromise care for non-FPP patients. “If FPP increases with the current workforce, care for non-FPP patients will be jeopardised,” Dr Drew said.

Dr Riz (pseudonym), who is currently pursuing a Master’s programme at a public teaching hospital, highlighted the need for more specialists to ease the burden of balancing both FPP and regular patients under current working hours and workload conditions.

“Specialists may need to work longer hours to accommodate both FPP and non-FPP patients. Managing this workload could become challenging, especially if demand increases,” Dr Riz said.

He also noted potential concerns about equity and access, as specialists might face criticism if FPP patients receive preferential treatment over non-paying patients. “The MOH needs to establish a method to balance FPP and public patients to ensure fairness,” Dr Riz added.

Dr Sam highlighted potential conflicts of interest, pointing out that a CT scan through the regular channel might take a month (though a fortnight is possible if staff are pushed), while FPP patients can potentially receive the diagnostic test on the same day of their visit.

In addition to manpower shortages and potential inequities in patient care, concerns have also been raised regarding FPP fees for staff, not just specialists, and legal liabilities.

Under the current FPP, revenue generated is shared between FPP specialists and the government at a regulated percentage based on the type of service provided.

“The support staff are not keen on facilitating the process, as they feel only the doctors profit from it; there should be an incentive for them too. So we used to pay them from our own pockets,” Dr Sam said.

Meanwhile, Dr Alex is worried about the legal complexities of having a private wing within a MOH hospital. “MOH cannot act as both the governing body and the service provider for private and government patients.

“If they want to implement this model, they should register it as a private hospital run by MOH staff and ensure it falls under the Private Healthcare Facilities and Services Act 1998 (PHFSA) – that would be the way to go. Otherwise, the conflict of interest is too big.”

Despite a general consensus on the associated risks, at least three of the five doctors interviewed by CodeBlue are open to the potential benefits of expanding FPP under RakanKKM, particularly in retaining specialists and providing opportunities for additional income.

“The biggest advantage, besides retention of specialists, is that we can do more complex cases and not worry so much as there would be enough support for post-op care. The team on the government side can help out if needed, and that would be the biggest selling point to both patients and doctors,” Dr Sam said.

Dr Riz said: “FPP allows greater flexibility in health care delivery and provides an option for patients who wish to access services on a paying basis, while still maintaining high-quality care. The FPP scheme can help reduce waiting times for non-full paying patients by allowing those who are willing and able to pay to access services more quickly.

“It’s crucial for MOH to ensure that the implementation of the FPP scheme will not affect the quality of care provided to regular patients, and it is also important for the MOH to be transparent on the revenue generated from FPP so the public knows where the money goes.

“Specialists under the FPP scheme will receive more income from services provided to full paying patients, which can lead to an increase in earnings, and can be a way to retain them in the system.”

Dr Sam said: “To be honest, it’s a good incentive, but among the patients we cater to in the government setting, only a select few can afford FPP. Most will have to wait and endure.

“Those with insurance typically won’t consider FPP because it doesn’t accept insurance, only cash, so they would go to a private hospital instead.”

Dr Sam, however, acknowledged the limitations of the current patient demographic, noting that while FPP is a good incentive, only a select few among the patients in MOH hospitals can afford it. “Most will still have to wait and endure.”