In general, when a person is infected by pathogens like bacteria and viruses, the body’s immune system fights back by producing proteins called antibodies, which bind to the pathogen, rendering it harmless, or identifies it for destruction by the body’s immune cells.

Antibodies usually stay around for a long time after an infection. When re-infection by the same pathogen occurs, the body’s immune response is much faster. This means that those who have recovered from the initial infection has resistance to re-infection.

The immune response to viruses varies widely. For example, chicken pox in childhood will usually lead to immunity to reinfection for the rest of life. With coronaviruses that cause the common cold and influenza, immunity fades after a few months, which is why people gets new infections year after year.

It is different with dengue – those infected a subsequent time by another dengue sub-type may get “antibody-dependent enhancement” in which the body’s immune response actually worsens the clinical symptoms and increases the risk of developing severe dengue.

On the other hand, infection with tetanus, caused by the bacterium, Clostridium tetani, is not protective at all – that is why regular booster shots of tetanus toxoid are required.

In short, there is an immunity spectrum in the body’s response to various pathogens.

SARS-CoV-2, which causes Covid-19, is a new infection as it had never affected humans till the end of 2019. The world is still learning about its behaviour and the disease it causes.

The body response to the first infection with SARS-CoV-2 depends on the viral dose received, one’s genetic background and one’s immune system’s programmed response to new infections. These are influenced by one’s general health and age which appears to affect the severity of Covid-19.

Most countries, including Malaysia, have implemented limited movements of their populations in an attempt to manage the burden of Covid-19. One of the considerations in the discussion on the lifting of these restrictions is antibody (also termed “serology”) testing. Can those who have been infected and recovered, and/or those who have no antibodies be allowed to go back to work?

Covid-19 Tests

There are two types of tests for Covid-19:

- PCR tests detect the presence of the nucleic acid of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes Covid-19, in the body. This is usually done by taking samples from the nasopharynx, throat or the lower respiratory tract;

- Serology tests detect whether the body has produced antibodies in response to Covid-19. This is usually done by taking a blood sample and testing it for specific antibodies.

The PCR test requires complex laboratory equipment and usually take several hours or even days for the results to be available. There are now some instruments available that can produce quicker results but they cannot do as many tests simultaneously.

PCR tests are considered more sensitive than serology tests for diagnosing early infection and as they detect viral RNA directly, they are indicators of viral shedding. The degree to which a positive PCR test correlate with the infectious state is still being determined. In a person who had been PCR positive, clinical resolution and consecutive negative PCR tests are currently used as criteria to determine recovery.

A positive PCR test means that the person tested is shedding virus and is used to diagnose those who can spread the infection to others. Most of those infected will have a negative PCR test about 20 days after it was first detected.

A PCR test cannot determine if a person had an infection in the past. It also does not help determine whether persons who have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 will develop Covid-19 in the 2 weeks after exposure. In some of those infected, the virus can be detected by PCR for only a few days at the beginning of the infection – in these situations, the test may be negative if the sample is taken more than a few days after the illness starts. In some others, the PCR test may be positive for more than 40 days after first detection although the person may not be actually infectious to others. In some others, those who have recovered and tested negative have returned later to test positive without symptoms.

There is a period of about five to seven days between infection with SARS-CoV-2 and the production of IgM and IgG antibodies which are detected by serology tests. IgM is the first antibody produced and it appears usually within one to two weeks. The body also produces the IgG antibody, which appears in tests about two weeks after the illness starts. In most infections, IgM usually disappears after a few months and the IgG can last for years. Whether this is the same with the SARS-CoV-2 virus is unknown – only time will tell.

A positive serology test means that the person tested has had an infection in the past and that the body has developed antibodies in response. It can help identify those who have had previous infection although they may have had no symptoms. It may be able to determine those who have some level of immunity to Covid-19.

In some others, it could help determine when the illness occurred since IgM is produced before IgG and IgM goes away before IgG. If there is widespread testing in the population, it can provide information what percentage of the population already had Covid-19.

Serology tests may be negative if done at the beginning of an infection – that is why it is not used to detect if a person has active infection and is infectious. Some serology tests may cross-react with other coronaviruses, leading to false results. Serology tests with low sensitivity and specificity will not produce reliable results.

In short, there are many gaps in the knowledge about the body’s response to the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

For example, one study reported no correlation between viral load and the presence of serum antibody responses (The Lancet 23 March 2020 DOI).

The data on antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 is also limited.

Sensitivity And Specificity

The reliability or accuracy of any test depends on its sensitivity and specificity.

Sensitivity refers to how often a test correctly produces a positive result for people who have the condition tested i.e. “true positive” rate. A highly sensitive test will detect almost everyone who has the condition and will not produce many false-negative results. For example, a test that is 90% sensitive will correctly detect 90% of people who have the condition, but will not detect 10% of people who have the condition and should have been tested positive – this is termed “false-negative”.

Specificity refers to how often a test correctly produces a negative result for people who do not have the condition tested i.e. “true negative” rate. A highly specific test will detect almost everyone who do not have the condition and will not produce many false-positive results. For example, a test that is 90% specific will correctly detect 90% of people who do not have the condition, but will detect 10% of people who do not have the condition and should have been tested negative – this is termed “false-positive.”

The sensitivity and specificity of tests exist in a state of balance. High sensitivity i.e. the ability to correctly detect people who have the condition, usually is at the expense of reduced specificity i.e. more false positives. Similarly, high specificity i.e. the ability to correctly detect people who do not have the condition, usually is at the expense of reduced sensitivity i.e. more false negatives.

This is illustrated by pregnancy tests. For example, a pregnancy test has a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 95%.

• Sensitivity – 95 out of 100 pregnant will be correctly identified;

• Specificity – 95 out of 100 who are not pregnant will be correctly identified;

• False negative – 5 out of 100 pregnant will not be correctly identified;

• False positive – 5 out 100 who are not pregnant will not be correctly identified.

The current gold standard for Covid-19 diagnostic testing is the PCR test, which is relied on globally. Most PCR tests have sensitivity and specificity of 90% or more. This means that 90% or more of those who test positive truly have the SARS-CoV-2 virus and that 90% or more will not slip through as a false negative.

As both the sensitivity and specificity of the PCR test are not 100%, there will be instances of false positives and false negatives. The sensitivity and specificity of serology tests vary leading also to instances of false positives and false negatives. The reasons for these occurrences have been addressed in previous paragraphs of this article.

Serology Tests For Covid-19

There are different types of serology tests viz:

• Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) is a common laboratory platform that can measure antibody titres;

• Lateral flow assays provide a simple positive or negative result with no quantitative information;

• Chemiluminescence immunoassays are closer in concept to ELISAs than lateral flow assays as the tests generate a light signal proportional to the IgM antibodies.

The World Health Organization (“WHO”) has a list of serology tests used by its member states. None of these tests have been endorsed by the WHO.

The WHO’s position on antibody tests is clear i.e. “Laboratory tests that detect antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in people, including rapid immunodiagnostic tests, need further validation to determine their accuracy and reliability. Inaccurate immunodiagnostic tests may falsely categorise people in two ways.

“The first is that they may falsely label people who have been infected as negative, and the second is that people who have not been infected are falsely labelled as positive. Both errors have serious consequences and will affect control efforts. These tests also need to accurately distinguish between past infections from SARS-CoV-2 and those caused by the known set of six human coronaviruses.

“Four of these viruses cause the common cold and circulate widely. The remaining two are the viruses that cause Middle East Respiratory Syndrome and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. People infected by any one of these viruses may produce antibodies that cross-react with antibodies produced in response to infection with SARS-CoV-2.”

The WHO’s position on immunity is “At this point in the pandemic, there is not enough evidence about the effectiveness of antibody-mediated immunity to guarantee the accuracy of an ‘immunity passport’ or ‘risk-free certificate’. People who assume that they are immune to a second infection because they have received a positive test result may ignore public health advice. The use of such certificates may therefore increase the risks of continued transmission.”

Socso and Health Ministry

The Health Ministry has advised the Social Security Organization (“Socso”), which will be funding the testing of workers returning to work in industries approved by the government.

The serology tests recommended to be considered for use have been assessed by the Institute of Medical Research (“IMR”) and the National Public Health Laboratory (“MKAK”)

The recommended tests and the websites of their vendors are:

• Lionrun Shanghai Liangrun Diagnostics Kit

• Wondofo

• Vazyme

• STANDARD Q COVID-19 IgM/IgG Combo

• Healgen

Some of the vendors have provided information about the sensitivities and specificities of their serology tests in their websites; some have not. In general, the sensitivities are higher 8-14 days after the onset of symptoms and closer to 97-98% when about 21 days after the onset of symptoms.

It is regrettable that the Health Ministry has not disclosed the results of the evaluation of the serology tests by the IMR and MKAK. Did the evaluation authenticate the statements by the vendors?

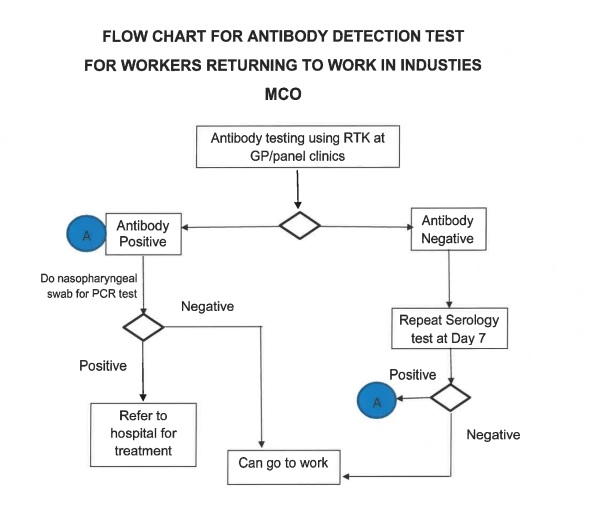

The Health Ministry’s flow chart for testing by general practitioners is below:

The antibody-positive have to get a PCR test. If negative, they can return to work.

Two antibody-negative tests taken seven days apart would permit a worker to return to work. Can such a worker have Covid-19? The answer is in the affirmative because the person’s antibody levels may not have reached a sufficient level for it to test positive at seven days and many of the infected have no symptoms.

It is essential for the Health Ministry to provide information to doctors, particularly general practitioners, about the PCR and serology tests recommended with regard to sensitivities, specificities and analytical specificities to ensure against interferents, notably cross-reactivity with other coronaviruses. This information will enable the provision of appropriate information to employers and employees.

Summary

• There are false positives and false negatives with both PCR and serology tests as their sensitivities and specificities are not 100%;

• PCR tests can usually determine whether a patient is infectious;

• Serology tests cannot determine whether a person is infectious;

• Serology tests are not able to detect if a person has been recently infected i.e. in the past week or so;

• An effective Covid-19 response relies on accurate and prompt reporting from all facilities that offer testing.

It would be prudent for all parties to remember the saying, caveat emptor, which is Latin for “Let the buyer beware.”

Dr Milton Lum is a past President of the Federation of Private Medical Practitioners Associations, Malaysia and the Malaysian Medical Association. This article is not intended to replace, dictate or define evaluation by a qualified doctor. The views expressed do not represent that of any organisation the writer is associated with.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.