KUALA LUMPUR, May 17 – At first glance, the People’s Income Initiative (IPR) for poor Malaysians to generate income from selling cooked food through government-sponsored vending machines seems easy enough.

The government covers overheads – the cost of electricity, lot rental, and rental of food vending machines – for the two-year IPR Food Entrepreneur Initiative (Insan) project that is open to the bottom 40 per cent (B40) and hardcore poor. Whereas the IPR participant “only” – in Economy Minister Mohd Rafizi Ramli’s own words – needs to come up with the working capital for their food products.

However, CodeBlue’s interviews with three IPR participants at the KL Sentral transit station revealed the hidden costs of the government initiative that plans to lift them out of poverty by the end of the two-year project, not least of which is compliance with food safety and hygiene in the highly regulated food & beverage (F&B) industry.

Other issues – which IPR participants want more government assistance on – include marketing, advertising and promotion, and even the startup capital itself that the hardcore poor completely lacks.

Retail prices for all cooked and perishable food products sold in the IPR vending machines – supplied by Nu Vending – are capped by the government at RM5.

All products in a single machine are sold by one person; there aren’t multiple IPR participants selling their products in the same vending machine. In KL Sentral, five IPR participants operate one food vending machine each. The IPR Insan programme at KL Sentral was launched last May 9.

Norfaridah Mohamad Noor, a 38-year-old woman who operates an IPR food vending machine next to a fast-food restaurant at KL Sentral, drives to and fro the transit station multiple times daily because she doesn’t want to fully stock the vending machine, restocking only when necessary to minimise losses from discarding unsold cooked food.

“Many people still don’t know about these vending machines,” Norfaridah told CodeBlue last Thursday.

Norfaridah is unemployed. So is her husband, who underwent a heart bypass surgery and wears a catheter bag due to other serious health conditions. The couple do not have other sources of earned income.

They live in a PPR flat in Kerinchi with six children aged seven to 17 years, two of whom have disabilities.

Welfare Money Used To Buy Custom Food Packaging

As Norfaridah’s family lives on monthly cash assistance of RM700 from government agencies, besides RM150 monthly credit for groceries, Norfaridah was forced to use welfare payments to buy food packaging for her IPR food vending machine business — the only item she’s spent capital on so far.

“As this programme is only three days old, I’m still using stuff in my house because during the fasting month, certain parties came to my house to give us dry goods for our own consumption. But I used it for my business instead,” Norfaridah told CodeBlue, with a grinning emoji in her text message.

The plastic packaging for food products in the IPR programme – of which participants are only allowed to purchase the type customised for the vending machine – is expensive for Norfaridah at RM35 for 100 packs. Other suppliers in Chow Kit, she pointed out, sell similar packaging at RM10 for 50 packs, 43 per cent cheaper.

“If I want to sell bee hoon for RM2 and I buy that [custom] packaging, it’s not worth it because the packaging is expensive.”

The cost of packaging at 35 sen per food pack already makes up 17.5 per cent of the RM2 retail price – excluding labour cost and the cost of raw ingredients (which Norfaridah is currently not spending on because of the donated dry goods she received) – cutting into narrow profit margins even further.

While she understood the government’s rationale for mandating standardised packaging to prevent food spillage, Norfaridah pointed out that placing her product of roti jala with three pieces would look small in a large pack to potential customers.

Norfaridah’s cekodok snack with sardine sambal is popular, as she receives requests on WhatsApp asking when she will restock the product in the vending machine.

‘Programme is Good, but Promotion Lacking’

Norfaridah – who is cooking food for the general public for the first time, through her IPR business – generally stocks the vending machine at 7am, collects any unsold stock and restocks with fresh products eight hours later at 3pm, and collects all unsold stock six hours later at 9pm.

“So far, other sellers and I don’t dare to put food out after 9pm. I myself am worried.”

However, Norfaridah also restocks periodically during the day whenever stocks run low, as the vending machine app shows real-time purchases of her products. Besides cekodok and roti jala, Norfaridah also sells white rice with sambal chicken, popcorn chicken with nachos sauce, and nasi himpit kuah kacang.

Interestingly, a very profitable product for Norfaridah is 300ml mineral water, sold at RM1 per bottle which she purchased at about 37 sen each (RM9 for 24 bottles), translating to 170 per cent gross profit – without packaging, ingredient, or labour costs too. Once, she saw, with the app, purchases of nine bottles of mineral water in the span of one minute.

Of the 210 slots in the IPR vending machine, 60 is for mineral water products, while 150 is for food products.

Last Wednesday, Norfaridah collected RM109 in earnings, but expressed dissatisfaction as she was unable to clear her stock. At KL Sentral, the city’s main transport hub, there are a few convenience stores selling ready-to-eat meals.

“I’m sad looking at how people criticised Rafizi Ramli. Actually, the IPR programme is good; that’s why I joined it. But I’m unsure about its promotion because people don’t know about it,” Norfaridah said.

“If I could open a table, then I could call customers to come. Or they could give us banners. Food in vending machines doesn’t seem very popular.”

Norfaridah urged the government to provide IPR participants with startup capital, highlighting her eight-member household with no income (aside from her vending machine business).

“I was quite sad on the first day because they instructed us to fill up all the slots, so I filled up all 150 slots, but I couldn’t finish selling them. I was quite sad that I had to throw the food out or give it to others. On the first day, I made a lot of losses,” Norfaridah lamented.

“We’re selling at RM2 or RM3 — how to make profit?”

It is unclear what the top priority of the IPR food vending machine programme is for the Ministry of Economy: to provide consumers with cheap food priced below RM5 or for IPR participants to maximise profit (for a chance to get out of poverty).

Both objectives may be incompatible, especially when low-income and hardcore poor IPR participants are hamstrung by retail price caps (which then limits the range and quality of foods they can sell).

This is unlike large established F&B businesses that can offset costs of the Rahmah Menu and make profit from their own signature products priced appropriately for their target market.

Norfaridah is likely already making profit from her vending machine business since she did not have to buy dry goods to make cooked food products, with her startup costing her “only” capital on food packaging, besides transport and labour costs.

But she will need to make enough profit – before her supply of donated dry goods runs out – to bankroll the next batch of ingredients for her food products and to purchase food packaging, to avoid dipping into welfare payments. At this point, marketing appears to be a luxury expense.

IPR Participant with Full-Time Job Makes Net Profit in First Week of Programme

Amirudin Ahmad Abdul Jalil tracks his operational expenditure for the IPR food vending machine that he operates next to a convenience store in KL Sentral.

The 28-year-old – the youngest of the five IPR participants at the transit station – is also planning stocking for the vending machine based on market traffic for the first two weeks of the programme.

So far, he has observed high traffic from 7am to 10am. Ideally, Amirudin Ahmad would like to sell two batches daily: breakfast and lunch.

“For now, we only prepare for breakfast first. We want to let them know us first. Then, we’ll try to add more to the batch,” Amirudin Ahmad told CodeBlue last Friday.

He only stocks 50 per cent of available slots in the food vending machine, due to wastage on the launch day in KL Sentral last May 9 when all 150 food slots were filled. Whatever stock left in the machine by 3pm or 4pm is cleared – retrieved by his wife who works at KL Sentral.

“I don’t add fresh stock; it hurts daily opex (operational expenditure).”

Amirudin Ahmad’s business strategy – which accounts for unsold stock – has turned out to be effective, as he not only broke even on subsequent days after the launch day, but even turned net profit of RM70 to RM100 daily in the first week of the programme.

“I think RM150 net profit would be a good achievement.”

Amirudin Ahmad, who lives in Keramat, has a full-time job at a construction firm in Puchong. He, along with his wife and in-laws, wake up at 3 to 4am to cook and package the food products at home.

Then, Amirudin Ahmad drops his wife off at work at KL Sentral, places the products in the vending machine, and goes to work – a two-hour commute. The couple do not have children as they just got married this year.

Amirudin Ahmad sells RM1 mineral water (300 ml), RM2 kuih ketayap, RM2 egg sandwiches, RM3 sardine sandwiches, RM4 fried noodles, and RM5 fried rice in the IPR vending machine from Mondays to Saturdays; so far, Sunday is his rest day.

As all IPR vending machines look identical – plastered with the words “Inisiatif Pendapatan Rakyat” and IPR logos on a white and red colour scheme – Amirudin Ahmad is considering setting his apart with banners.

“I think IPR is the branding to promote Rahmah foods,” he said, when asked if he was planning to place his own branding on the vending machine.

The Ministry of Economy has yet to put out any marketing materials profiling the KL Sentral IPR participants or their vending machine products, either on its official IPR website or its social media platforms, except infographics explaining the IPR programme.

Posts of the May 9 launch at KL Sentral simply show Rafizi with government and Malaysian Resources Corporation Berhad (MRCB) officials, instead of the minister introducing the IPR participants to the media and showcasing or sampling their vending machine products.

Towards the end of a video of the launch, posted on the Economy Ministry’s Facebook page, Amirudin Ahmad was seen next to Rafizi in front of the vending machine. The minister simply described Amirudin Ahmad to reporters as, “Ini penerima (this is a beneficiary)”, without saying the entrepreneur’s name or inviting him to share his testimony.

Amirudin Ahmad praised the Ministry of Economy’s effectiveness in getting potential participants registered for the IPR programme, saying that the selection process took only about three to four months.

“We needed to go through training conducted by the vending machine supplier, rehearsals one week prior to launch day, and then we needed to bring the food. Simple as that,” said Amirudin Ahmad. “I think they’re trying to reduce the bureaucracy of this programme.”

When asked why he decided to join the IPR programme, despite having a full-time job, he replied, “To gain extra income”. The 28-year-old also highlighted his previous experience running a restaurant business in a brick-and-mortar shop that also provided online food delivery.

“As entrepreneurs, we need to fork out some capital first, so that we become more responsible towards what we’re working on.”

IPR Participant Clears Most Stock, Yet to Calculate Earnings

Normaladiana Mohd Yazal, a 36-year-old woman who lives in a PPR flat in Kerinchi, said so far, she has managed to finish clearing most of her food products in the IPR vending machine that she operates near an exit at KL Sentral.

She sells RM1 mineral water (300 ml), RM2 for three curry puffs, RM2 Maggi goreng, RM2 nasi lemak, RM3 egg sandwiches, and RM4 chicken crab sandwiches.

“Yesterday, only two packs were left,” Normaladiana told CodeBlue last Thursday, adding that she may operate the vending machine every day.

When asked how much profit she has made so far, Normaladiana said she hadn’t counted it yet.

She usually places her cooked food items in the vending machine at 6am, sometimes 10am, replaces or restocks the products when necessary, and then collects unsold stock at 6pm or after eight hours.

“Sometimes it’s difficult because of transport,” Normaladiana said.

For her trips to and fro KL Sentral thrice daily for her vending machine business, Normaladiana either travels via e-hailing or in a personal vehicle with her husband or friends. “It’s not very expensive because I don’t live very far from KL Sentral.”

Normaladiana also runs a separate sandwich delivery business from home. She and her husband, who works as a cleaner, have two children aged 10 and 13 years.

Health Inspector Highlights Potential Food Safety Issues: Missing Food Expiration Labels, Excessively Warm Vending Machine Operating Temperature, Cross-Contamination from Improper Food Packaging

An environmental health officer, also known as a health inspector, from the Ministry of Health (MOH) highlighted several potential food safety and hygiene issues with IPR’s ready-to-eat (RTE) food vending machines, speaking on condition of anonymity as civil servants are prohibited from speaking to the press without prior authorisation.

The health inspector – who previously conducted restaurant health inspections – provided comments to CodeBlue based on descriptions and photographs of IPR vending machines at KL Sentral taken from CodeBlue’s site visits last May 11 and 13. He did not personally inspect the vending machines.

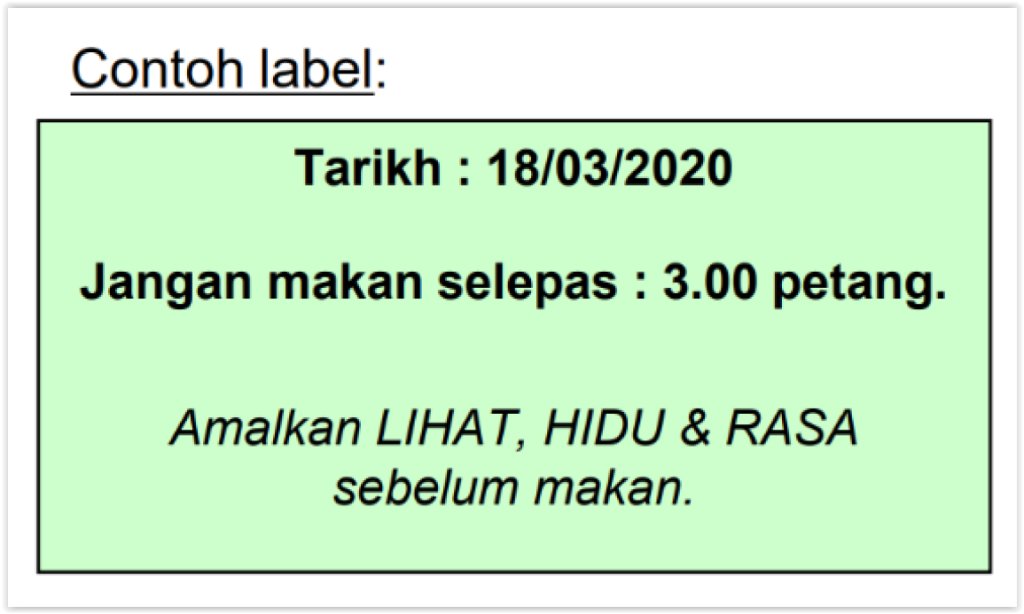

One of the requirements for RTE food vending machines is food expiration labels (Label Panduan Waktu Makan) on packaged food that state the date and time for when the product is no longer safe for consumption, said the health inspector.

RTE food must be served and consumed not more than four hours after it is cooked, he added. For example, if cooking of the food was completed by 11am, the packaged food must be served at room temperature and consumed by 3pm, after which it must be disposed of.

A sample use-by label provided by the health inspector states the date and time by which the food must be consumed, along with the phrase: “Amalkan LIHAT, HIDU & RASA sebelum makan” (See, Smell & Taste before consumption).

None of the RTE food products in all five IPR vending machines at KL Sentral have food expiration labels. Norfaridah, Normaladiana, and Amirudin Ahmad told CodeBlue that they dispose of unsold cooked food products only about eight hours after they are placed in the vending machines, instead of four hours after they are cooked.

The health inspector was alarmed at the operating temperature of IPR’s RTE food vending machines. The five IPR vending machines at KL Sentral displayed operating temperatures of between 18 and 24 degrees Celsius during CodeBlue’s site visits last May 11 and May 13.

“Regulations under the Food Act mandate that cooked food be served and consumed within four hours. Storage in machines at between 18 and 24 degrees Celsius is extremely risky and inappropriate; the permitted temperature for chillers is between 4 and 10 degrees Celsius,” the health inspector told CodeBlue.

Based on specifications of the IPR vending machines supplied by Nu Vending, the machine’s cooling temperature can actually be controlled down to 4 degrees Celsius.

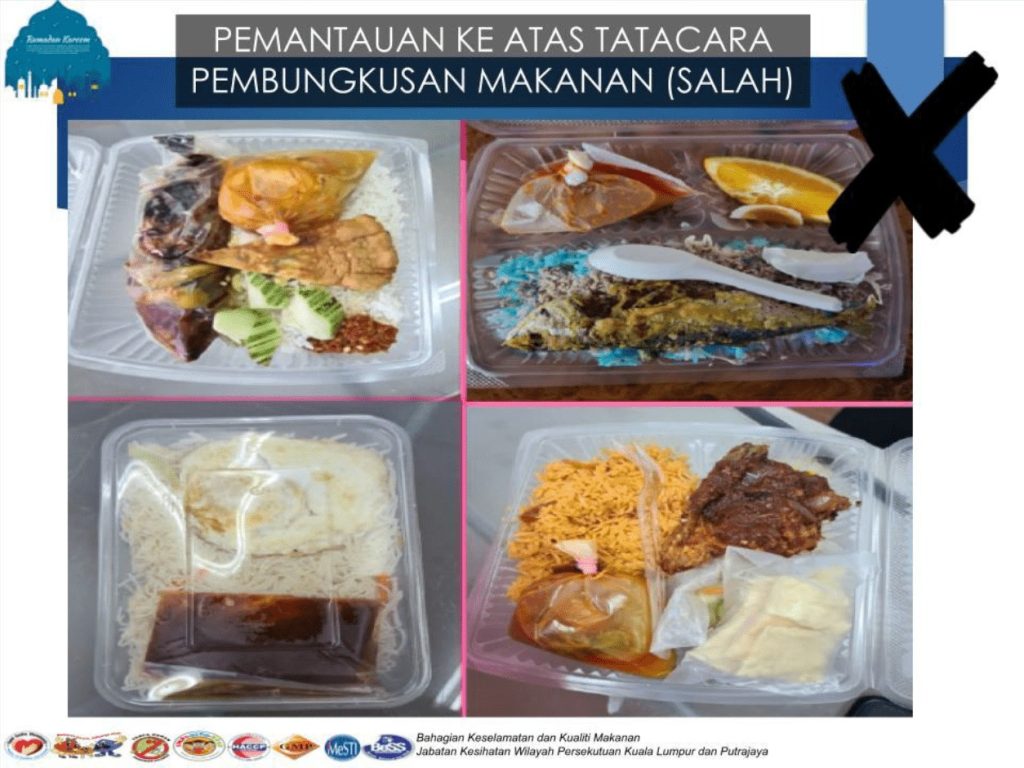

The health inspector also expressed concern with the inclusion of non-food items in the food packs sold in IPR’s RTE food vending machines. The IPR vending machines with food products like cooked rice and noodles package plastic spoons in direct contact with the food.

“Providing the plastic spoon is not against the law, but looking at the photos, the spoon should not be placed in direct contact with the food, as the cleanliness of the spoon cannot be guaranteed and, as such, can cause cross-contamination,” said the health inspector.

“The spoon should be included, but not placed directly with the food like that; the food should be packaged separately.”

Some products sold in the IPR vending machines at KL Sentral contain food (like cooked meat) packed in a plastic bag and tied with a rubber band, which is placed in direct contact with cooked rice in the plastic package.

“The plastic and rubber band used for packaging must be clean and free of contamination to avoid cross-contamination,” the health inspector said.

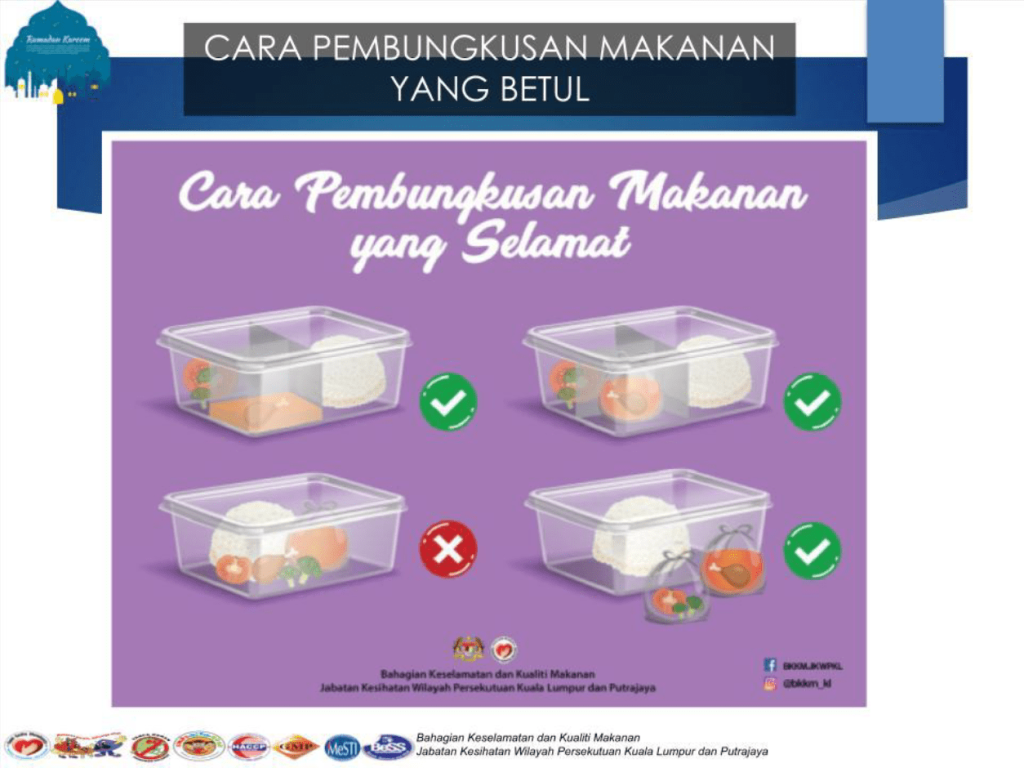

A food packaging graphic from the Food Safety and Quality Division at the Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya Federal Territories Health Department, which the health inspector shared with CodeBlue, shows that it is prohibited to package cooked food products like rice or noodles together with utensils and other separately packed food dishes in the same container without compartments.

Instead, individual food items must be compartmentalised from each in a single container, or each food item must be packed and provided separately.

“It is mandatory to ensure that sold food is not exposed and does not carry the risk of cross-contamination. Packaging that completely covers the entire food product is a must,” the health inspector added.

More Food Safety and Hygiene Rules: Food Packaging and Transportation, Vending Machine Cleaning and Pest Control Services

The health inspector from MOH listed other requirements for those preparing and selling cooked food products in RTE food vending machines.

On packaging RTE food, the area and equipment used for packaging the food must be cleaned. Hands must be washed before and after wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), like clean aprons, head coverings, and mouth coverings.

The food must be packaged on a clean table in clean surroundings. Clean and appropriate equipment must be used, like tongs or ladles. “NEVER touch food using your hands,” the health inspector said.

On the cleanliness of RTE food vending machines, the health inspector said the machines must be cleaned “immediately” if there is any food or drink spillage, with daily monitoring required to ensure cleanliness.

“Using regular household cleaning products without any particular specifications is encouraged, but the right volume must be used to prevent excess chemicals that may contaminate food,” the health inspector said.

“It’s not only the surrounding environment that needs to be clean, but the machine itself must be proofed against the entry of pests (cockroaches, flies, and mice).”

RTE food vending machines must not have any openings to prevent the entry of pests, the vending machine must always be clean, the trash can must always be closed (if one is provided; this is not a requirement for takeaway food from vending machines), and services from a pest control company must be obtained to manage the pest control system for the vending machines.

Both Normaladiana and Norfaridah told CodeBlue that they clean their respective IPR food vending machines whenever they restock products. Amirudin Ahmad said vending machine technicians told IPR participants to do minor cleanings of the machine every day and a major one every week.

It is unclear who is legally responsible for engaging pest control services or maintaining the cleanliness of the vending machines’ surrounding environment: the IPR participant, the vending machine supplier, the Ministry of Economy, or MRCB as the owner of KL Sentral.

Further, it is not clear who will be held legally liable for any breaches of Regulation 54 (food vending machine) in the Food Hygiene Regulations 2009: the government (Ministry of Economy) as owner of the machine or the IPR participant as operator of the machine.

Violations of Regulation 54 are punishable, upon conviction, with a fine not exceeding RM10,000 or imprisonment not more than two years.

Rafizi’s press secretary Farhan Iqbal tweeted last May 11 that the Ministry of Economy rents the machines for the participants, while the IPR participants own the goods they sell.

On transportation of cooked food, the health inspector said the food transportation must be clean and function well. The vehicle’s windows must be in a good condition (not cracked or broken). The vehicle used must be appropriate for the volume of food transported.

Food and non-food items cannot be mixed during transportation, while the vehicle for food transportation cannot transport toxic or poisonous substances. Maintaining a cold chain is not required for cooked food that is served at room temperature.

Norfaridah, Amirudin Ahmad, and Normaladiana said they cook, prepare, and package their food products in their homes, before transporting the food products to KL Sentral in their personal vehicles and placing it in the vending machines for sale. Normaladiana also sometimes transports her food products in her travels to KL Sentral via e-hailing.

All three IPR participants said they took typhoid jabs and underwent a course on food handling for certification as part of the programme, before starting their vending machine business.

They also said health inspectors have yet to check their personal kitchens that are used for the vending machine business, although this may not be necessary given that they have already been trained and certified.

The health inspector interviewed by CodeBlue said his department has yet to make policies or receive information related to the IPR Insan food vending machine programme, when asked if MOH was required to inspect IPR participants’ kitchens, their food transportation, or the vending machines.

The punishment for contraventions of any regulations made under the Food Act 1983 is a fine not exceeding RM10,000 or a maximum two-year jail term.

“IPR self-service vending machines are treated the same as other F&B businesses,” Rafizi’s press secretary Farhan tweeted last May 12, explaining the rationale for the machines displaying the IPR participant’s name, address, and phone number that are standard details of businesses, like for business licences. (IPR participants’ addresses have since been removed from the machine’s touch screen that now only shows their name and number).

IPR Participants Lack Resources for Full Food Safety and Hygiene Compliance

“It would be better if we had expiry date labels, but it’s all extra cost,” Norfaridah told CodeBlue. “We’re selling at cheap prices. I’m also unsure as to how to put the labels.”

Amirudin Ahmad acknowledged CodeBlue’s concerns about the absence of food expiration labels, but said he did not think there was a need for such as generally, in Malaysia, cooked meals are prepared on the day itself or some hours prior to sale.

“I’m not sure how to deliver this [food expiration labels]. I think there’s no need for expiry date labels, since they know the food is fresh and packed,” he said.

“When you talk about the regulations, some of the regulations – there’s some grey areas to this. I think some of the regulations – we cannot deliver because we don’t have good resources. We’re not saying we’re against the limitations, but the capabilities we have right now are hindering us from fulfilling requirements.

“The government has helped us on this programme – reduced bureaucracy, reduced requirements – but still, like I said, safety is primary. So I think what they can do to improve – there’s always room for improvement – is to conduct weekly checks on the site, the vending machines especially.”

Although most people get mildly sick from food poisoning, some infections spread by food are serious or even life-threatening. Food poisoning may cause hospitalisation, as well as other long-term health problems, according to the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In Malaysia, a food poisoning outbreak in 2018, caused by Salmonella bacteria found in laksa noodles sold at a food stall in Baling, Kedah, killed two people and sickened 81 others.

Amirudin Ahmad stressed that food safety and hygiene should be top priority in the IPR Insan vending machine programme.

“The problem may not occur now, but we’ll see it a few months later if we don’t take care of food hygiene and safety.”

In response to CodeBlue’s multiple questions on food safety and hygiene issues, the Ministry of Economy acknowledged CodeBlue’s concerns about the absence of food expiration labels on products sold in the IPR food vending machines.

“The IPR vending machine is operated by participants that were identified from the hardcore poor, poor, and B40 groups to help them generate additional income. This programme is still at the pilot programme stage and being fine-tuned,” Mohd Fairuz Azmi, deputy director-general of the Poverty Unit at the Economy Ministry’s Equity Development Division, told CodeBlue in a brief statement yesterday.

“In ensuring the food safety aspect, the Ministry of Economy has cooperated with the Ministry of Health Malaysia for guidance pertaining to food safety for food sold at IPR vending machines. As this programme has just been introduced at the beginning of 2023, there are still areas that need to be improved and this is a work in progress.

“The Ministry of Economy is taking steps to rectify the issue related to food safety.”

Bernama reported Rafizi as saying last March, at the launch of the IPR food vending machine programme at the Terminal 1 Bus Station in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, that the Economy Ministry planned to expand the initiative to 5,000 participants this year. The cost of the vending machine rental, which is covered by the government, amounts to between RM600 and RM800 monthly.

The entire IPR programme – comprising the Agro Entrepreneur Initiative (Intan), Insan, and the Services Operator Initiative (Ikhsan) – was allocated RM750 million under Budget 2023. It’s unclear how much of the sum has been allocated to regulatory compliance for Insan, or if IPR participants are expected to bear the regulatory cost of their vending machine business.