KUALA LUMPUR, Feb 17 – Living with any disease can be challenging, but patients with rare conditions often deal with uniquely difficult problems – from getting the right diagnosis to appropriate treatment that is affordable and locally accessible.

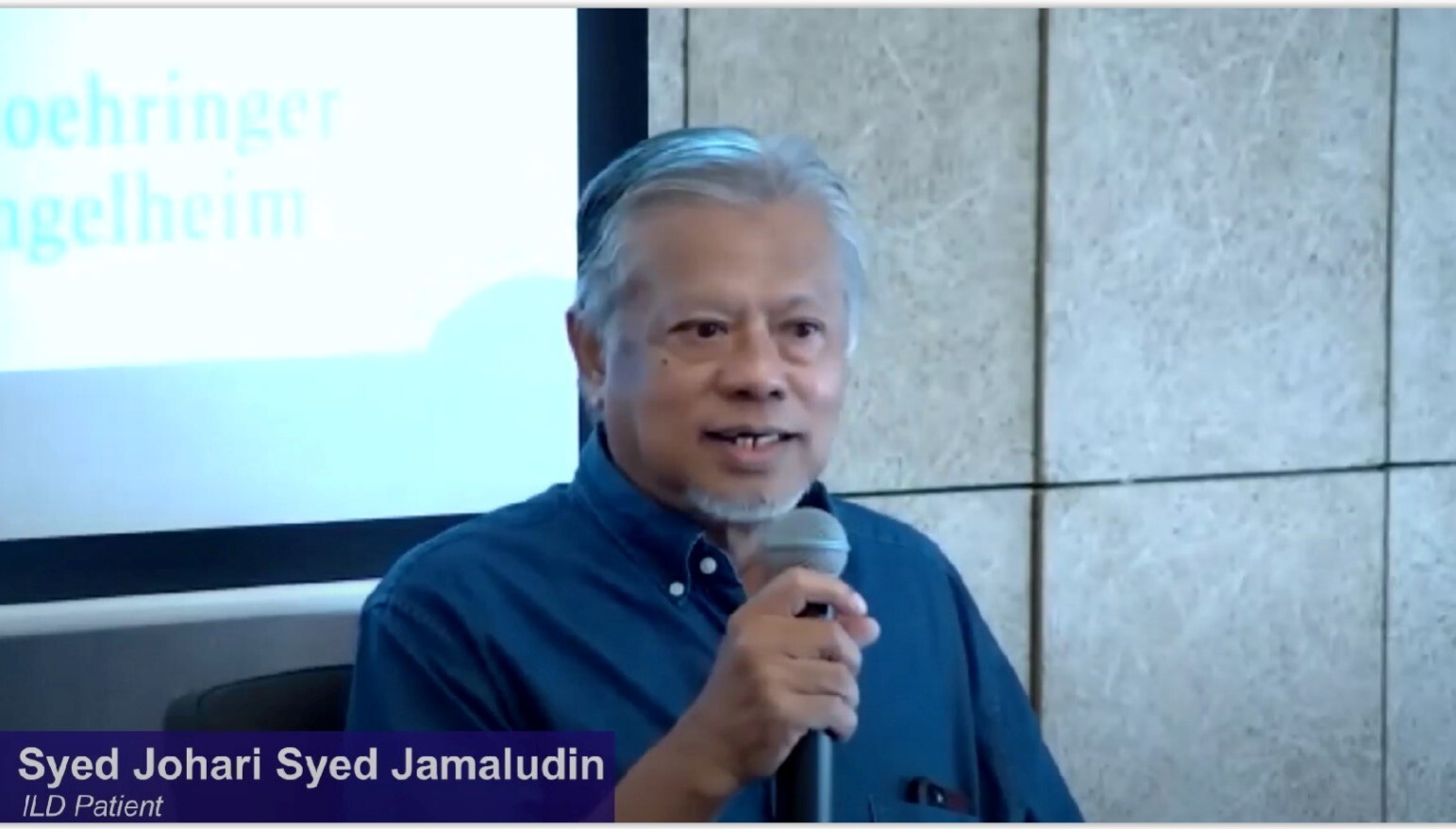

For Syed Johari Syed Jamaludin, it took six months, two different private hospital visits, two lung specialists’ consultations, an episode of hospitalisation, five days of antibiotics treatment, multiple scans and tests, and a biopsy before he was finally diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a type of rare lung disease that causes scarring and stiffness in the lungs.

The word “idiopathic” means it has unknown causes. Scarring causes stiffness in the lungs and eventually, making it difficult to breathe.

“Sometimes when I cough, I would pass out. It was that bad due to the low oxygen level,” Syed Johari shared at the “Interstitial Lung Disease in Malaysia” Symposium, organised by the Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy and supported by Boehringer Ingelheim last October 21.

Lung damage from IPF is irreversible and progressive, meaning it gets worse over time. In some cases, the progression can be slowed down by certain medications, according to the American Lung Association. In some cases, people with IPF may be recommended for lung transplant.

Syed Johari said his symptoms included hard persistent, dry coughs that lasted for months, and frequent shortness of breath. It took another three months from the diagnosis before he could get the medication he needed.

“My doctor said fortunately, we have medicine to treat this. Before this, they would just give you antihistamine and allergy medications – montelukast and loratadine.”

“At that time, anti-fibrotic was not available in this country. So my doctor had to ask for an AP (approved permit) from the Drug Control Authority to get the drug in and that took another three months,” Syed Johari said. “And I was fortunate enough I had the money to buy it. It was very expensive.”

Syed Johari shared that he took anti-fibrotic for a year. After one year, Syed Johari said he was running out of money to buy the medicine.

“So I told my doctor, and coincidentally, my daughter is a pharmacist. She told me to get my doctor to refer me to IPR (Institute of Respiratory Medicine). We didn’t know about IPR because to us, IPR was a tuberculosis hospital.

“So I was referred to IPR. It took another five months to obtain the drugs.”

Despite his existing treatment, his condition worsened. “Now, every time I coughed, I had chest pains. And, as I told my consultant this morning, I had a bit of anxiety,” Syed Johari said. “I cannot go out because I talk lesser now. I couldn’t socialise now. Because of this condition, I don’t have anybody to talk to except for my wife.”

Syed Johari said he hopes to be part of the next clinical trials for an IPF drug in hopes to get better. “Give me anything; I will take it.”

IPF And Interstitial Lung Disease

IPF is an interstitial lung disease (ILD), an umbrella term used for a large group of diseases that cause scarring, or fibrosis, of the lungs.

According to a White Paper by the Galen Centre titled “Interstitial Lung Disease in Malaysia”, ILDs have an estimated prevalence of 67 to 98 cases per 100,000 and incidence of 19 to 32 cases per 100,000 per year in the general population, making it a rare disease. In Malaysia, it is estimated to affect more than 80,000 people annually.

Though current understanding of the condition implies that it mainly affects those who are middle-aged above the age of 50 and the elderly, when diagnosed correctly, paediatric cases have been detected.

Due to environmental exposure and occupational factors, those who are younger could also be susceptible to the disease. More men than women are affected by ILDs.

Diagnosing ILDs remains a major hurdle. They are normally diagnosed using a combination of pulmonary function tests, imaging, and biopsy. Presentation of clinical symptoms include dyspnoea (shortness of breath) and severe coughing, resulting in pulmonary fibrosis often being mistaken for asthma or other respiratory diseases due to the similarities of the symptoms.

Shortness of breath and a persistent dry cough are the most common early indicators.

Many of those living with this condition are often unaware and remain undiagnosed for long periods of time, seeking treatment only when conditions become dire or life-threatening.

Clinicians and health care professionals may also have poor disease awareness, leading to mistaken diagnosis, mislabelling (often for asthma), and poor follow-up care.

The median survival rate from a diagnosis of IPF is approximately two to five years. Though there is no cure, effective treatments are available to slow the progression of the condition, especially when diagnosed earlier.

Treatment includes pulmonary rehabilitation, oxygen therapy, medication, and surgery (i.e., lung transplant). It might also involve lifestyle changes, including smoking cessation and avoidance of environmental pollutants.

With medication, it is possible to lessen or reduce inflammation and scarring, depending on the underlying cause and severity of the condition. Getting the right diagnosis early, combined with effective treatment, can enable patients living with ILD to have full and active lives.

Challenges For ILD In Malaysia

Dr Syazatul Syakirin, a respiratory physician at the Ministry of Health’s (MOH) IPR, said Malaysia does not have proper data on ILD. “We don’t have a proper registry yet for ILD and I hope this will be in the future pipeline.”

Apart from the lack or absence of quality data, Dr Syazatul Syakirin said not all clinicians in the country are familiar with ILD, which contributes to the delay in diagnosis and treatment initiation. Additionally, the nation has limited doctors with special interest in ILD.

Testing for ILD is also a challenge, Dr Syazatul Syakirin said, “Some of the basic tests are available in our MOH facilities but some other tests, we need to outsource, especially for extended connective tissue panels and some of the tests are not done in government facilities.”

“Our patients have to spend their own money to pay at private labs. The advantage of doing in private labs is the turnaround time is of course very fast. They may get their results within three to five working days which would expedite the work out diagnosis for the patient.”

Dr Syazatul Syakirin said treatment for ILD is only available in certain MOH facilities.

“[They’re] only available in sub-specialised centres, particularly tertiary centres, and this is also one of the reasons for delays in treatment. The accessibility [of the treatment] is not easy, especially when we talk about antifibrotics due to the huge cost to MOH.

“We will go with other funding means, besides [relying on] MOH’s budget. If let’s say the patient is a pensioner, we will use the pensioner fund or if the patient is a Muslim, we will use zakat or baitulmal funding to get the treatment.

“But again, this process doesn’t happen in days or weeks. It may take even months, sometimes half a year, to get the funding to purchase the medication. So that will cause the delay in starting the treatment due to the limited access to treatment.

“We have one of the antifibrotics only in our formulary and itis licensed for IPF only. Apart from that, we would have to get approval from the Health director general, so that’s another process. After that step, and that would take four to eight weeks, depending on the locality, then only you can work out on the fundings,” Dr Syazatul Syakirin said.

According to Dr Syazatul Syakirin, there are 41 respiratory physicians in Malaysia. Of the total, five went for ILD training, with one now serving in the private sector. Respiratory physicians are spread across MOH, Ministry of Higher Education, and Ministry of Defence hospitals.