In a different multiverse, this column ceases to be since the columnist dies.

There were a few tears shed by the odd reader and casual bystander at the funeral, in that alternate reality. And flowers.

In this universe, the columnist died too. Only to return. So, to persist with bad jokes.

Yes, I lay on a court without a pulse for over a minute. Strictly speaking, dead.

Through a combination of (dumb?) luck, love, inspiration and participation, I sit on a hospital bed alive a week later. Today, as this goes online, I’d be undergoing my angiogram and thereafter the appropriate treatment.

What transpired last Thursday, the first of 2023, January 5?

As usual, I was at the club for my open-air futsal session. Tucked neatly behind the Intermark building, most city folks are unaware of Kelab Aman.

Here twice weekly, for two hours, we pretend to be fit, by running up and down the fenced up court adjacent to the two football pitches and hockey court. The main building houses two bars, a restaurant, gym and an upstairs multipurpose event space.

Preceding kick-off, I took a midnight bus from JB, rested uneasily before heading off to work, had chicken rice before two whole durians, picked up my gear which came with the team kit bag and walked three kilometres through KLCC to Kelab Aman to avoid being stuck in peak traffic in a Grab. Stupid much?

I wobbled a bit and ditched some of the contents in the trash. Trudged on to the club.

Exhausted would be an understatement. Just to give it its proper cherry on top, in the warm-up, one of the boys hits a sweet shot from five metres at my left eye.

Twenty minutes into the game, our five-a-side with single rotating substitutes, I step away from play to the side netting field side, and say the words, “Guys, I need a minute. I’m feeling light-headed.”

Things fade. A major heart attack was in motion.

The next 20 minutes are gathered from multiple recollections of the other players. This player remembers nothing. He WAS the event.

I partially tangled with the side netting and in seconds collapsed to the ground. Mike got hold of me and checked for a pulse. He said there was not much of it on my neck and wrist. My neck had swollen and my tongue out as I gasped for air.

Meanwhile, the other lads scampered furiously around the club — the bar, the changing rooms, the management office — to find a doctor. Boys in shorts screaming for help.

There was one dining with her family. She had just returned from London the day prior.

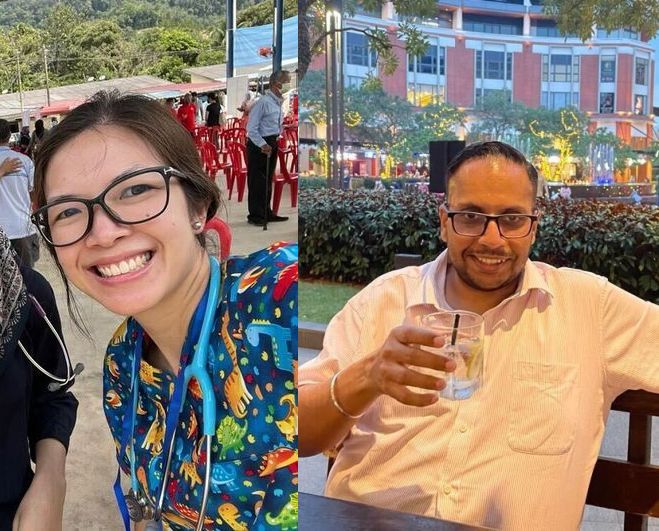

She’s a paediatrician. Best name I got was Angeline, from Mike. [Mike initially misidentified the doctor; she is actually Dr Abigail Choong Ai Ling from Tengku Ampuan Rahimah Klang Hospital (HTAR)]. She got to the court, and was shortly joined by another doctor from the hockey playing group from the other end. His name is still not made known.

(My friend, CodeBlue editor-in-chief Boo Su-Lyn, later told me that the other doctor was Dr Jagdev Singh, a medical officer from Kuala Kubu Bharu Hospital).

Dr Abigail initiated CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation). And Dr Jagdev, along with Rabten and Manuel, took turns to try to revive me. At one juncture, Mathias had returned with the club-owned automated external defibrillator (AED).

They messed about to figure out the contraption, before the pads were placed on my chest. Press the ON switch, the machine asked for more CPR.

The pulse was weak, and then the heart resuscitated partially. Everyone from the club, from the various sports and social spaces had formed a crowd around the futsal court. The floodlights made it into more of a spectacle. They applauded at the news of recovery.

It was premature.

Pulse dropped till there was none. The CPR continued more furiously. Manuel relates his experience later, he knew my rib could end up fractured or broken but he did not care. His friend was dying or perhaps already dead.

It is not working out. The manual resuscitation effort second time around. They estimate I was without a pulse for 90 seconds. The machine acknowledges that status. Asks everyone to step back and to press the defibrillate button.

Like on TV, apparently. The torso jumps up, and I return.

It took a few minutes for me to steady up and I asked to be sat up.

The doctor asks, “What’s your name.” Prolonged loss of oxygen, the worst fears linger.

The columnist answers, and it rattles me to think of it, whether it’s something or the typical moronic lines I spout on a whim. “My first name or my reincarnate name?”

What was that?

I spared everyone any idiocy when it came to my birth date, and recognising the full names of the players around me.

Me quipping to Mike that the doctor was pretty was key to the lads later together feeling convinced things will be OK.

I walked to the ambulance. Yes, it showed up. Twenty-five minutes later from HKL, which is two kilometres away.

One ride to HKL’s emergency room, an assessment was made and I was in an hour on the second ride to the National Heart Institute (Institut Jantung Negara-IJN).

There’s surreal, and there’s surreal.

What lessons to pull from the events? Maybe lessons are for another day.

Let’s go with gratitude.

I shudder to think if this happened at any of the other pitches I frequent across the Klang Valley. The group of lads and how they reacted made all the difference.

I had four persons — two of them doctors — to perform CPR on me. The club had an AED, it was operational and all the staff members were informed on how to get it immediately.

It was not locked up in a storeroom with the janitor out for coffee at the mamak. People did not impede each other. They worked together.

In the last 20 years, in social sports, word arrives of unfortunate deaths at playing fields. Here and there. I’ve not heard of a successful recovery.

The American Heart Association says more than 300,000 heart attacks or cardiac arrests happen outside a medical facility annually. And 89 per cent of them end in death.

I fear, not without reason, the survival rate would be far, far lower in Malaysia. Our facilities, our CPR trained individual numbers, our AED presences and our opposite of rapid-response ambulances.

With all the percentages set against me, I survived. It had nothing to do with me, and everything to do with the universe conspiring to bring all that’s necessary to one spot in Kuala Lumpur.

Oh, yeah. In those various tragedies before the only by-product would be pictures and videos. Of people dying or dead.

In my story, there were no photographers on court.

Maybe there’s one lesson. Helping is not foolhardy. I am walking proof of that.

This article was republished with permission from Malay Mail: “Dead man walks, a column continues”. Praba Ganesan is a columnist with Malay Mail.

Editor’s note: This article was corrected on January 13 to provide the correct identities of the two doctors who performed CPR on Praba — they are Dr Abigail Choong Ai Ling from HTAR Klang and Dr Jagdev Singh from Kuala Kubu Bharu Hospital.

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.