PETALING JAYA, Dec 30 — Malaysia should consider adopting a value-based approach to finance health care services, instead of the current fee-for-service payment model in which doctors, hospitals, and medical practices charge separately for each service they perform.

Prof Kenneth Lee Kwing Chin, a health economist at Taylor’s University’s School of Pharmacy, described health care as “inelastic” or inflexible when it comes to supply and demand principles.

The constantly higher demand for health care products and services often means that there is little room for both medication and services prices to fall, Lee said.

“Demand is always on the rise, and yet prices are also increasing, and sometimes it is faster than inflation rates. The increasing use of health care resources is most likely due to an inappropriate focus on the volume rather than the value of care.

“This has contributed to the surge of health costs,” Lee said at the 6th Health Economics Forum 2022 here last November 23 organised by the Health Economics Outcomes Research (hEOR), a unit of the Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy.

Hence, Lee is proposing a value for health care approach, which requires a shift in narrative from quantity of care to the quality and outcomes of health care.

In the traditional fee-for-service reimbursement model, health care providers are paid for the number of services they perform. This incentivises many providers to order more tests and procedures and manage more patients to get paid more.

Under fee-for-service models, the health care industry has been spending more to treat patients, even though patient outcomes were not necessarily improving.

Value-based care models, however, centre on patient outcomes and how well health care providers can improve quality of care based on specific measures, such as reducing hospital readmissions and improving preventative care.

Value-based care seeks to advance the triple aim of providing better care for individuals, improving population health management strategies, and reducing health care costs.

This rethinking of health care financing is based on an article published in 2010 in the New England Journal of Medicine by Michael E. Porter from Harvard Business School. The article places emphasis on making value the defining element in the framework for performance improvement in health care.

According to Porter, value should always be defined around the customer (patient). And as value is dependent on outcomes, he states that value in health care is measured by the outcomes achieved and not the volume of services delivered.

To better understand the outcomes of such a move, Lee drew attention to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), colloquially known as Obamacare, as an example of value-based versus quantity-based approach.

Enacted in 2010, the ACA had three primary goals: to make affordable health insurance available to more people, to expand the Medicaid programe to cover all adults with income below 138 per cent of the federal poverty level (FPL), and to support innovative medical care delivery methods designed to lower the costs of health care generally.

The Act was intended to expand access to insurance, increase consumer protections, emphasise prevention and wellness, improve quality and system performance, expand the health workforce, and curb rising health care costs.

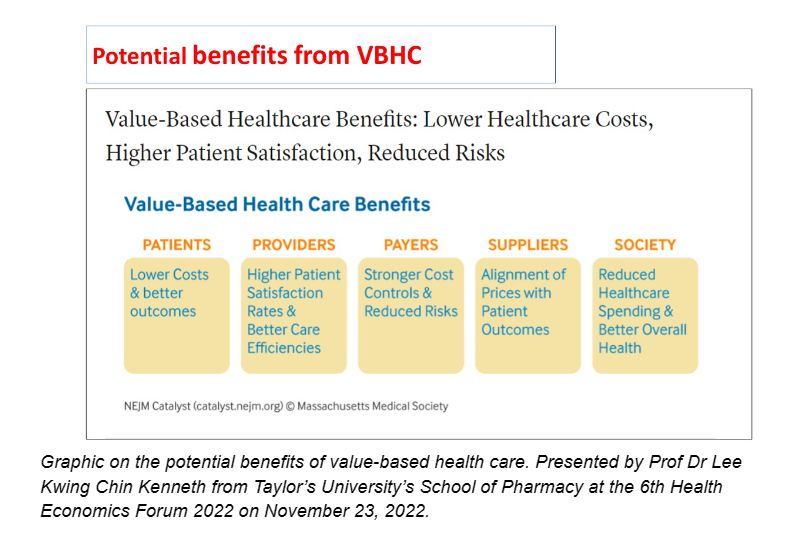

“This is a traditional fee for service health care. And this is a fee-for-value health care. Less money is used, but then strikes a balance between the quality of your service and money you put in. There are potential benefits for value-based health care.

“So for patients, they can pay less but with better outcomes,” Lee said. “For providers, they will have higher patient satisfaction rates and better care efficiencies.

“For payers, the control on costs is better and the risk of spending is less. For suppliers of health technologies, they’ll be able to align their prices with patient outcomes better. For the overall society, health care spending can potentially be reduced but with better overall health.”

Although this model is not a catch-all solution to the health care system’s problems, Lee said it is a “worthwhile improvement” to the traditional fee-for-service health care model.

Drawing lessons and problems from the Covid-19 pandemic, Lee said the pandemic revealed inequities and inequalities in most health care systems across the world.

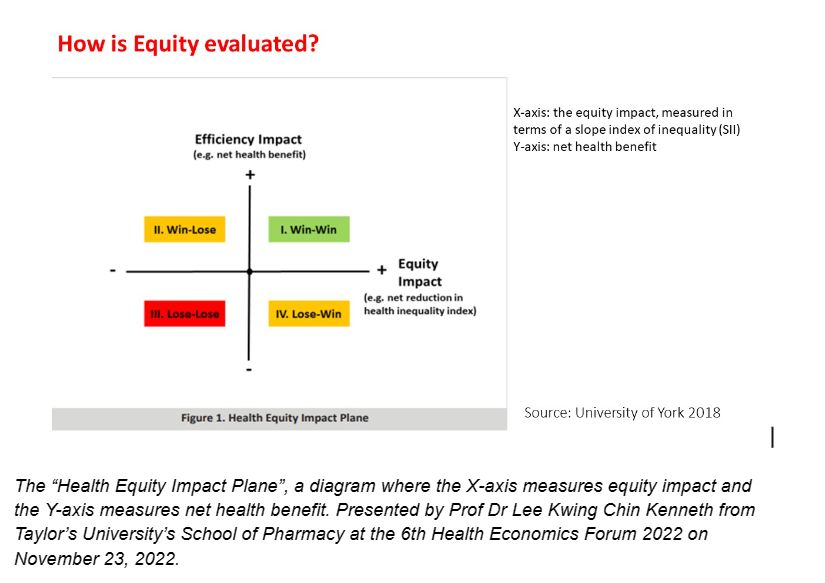

However, achieving a win-win situation in both these areas will not be an easy feat. To illustrate his point, Lee pointed to what he calls the “Health Equity Impact Plane”, a diagram where the X-axis measures equity impact and the Y-axis measures net health benefit.

“At least from my personal perspective, the Covid-19 pandemic has revealed two very important points of inequality and inequity. The first one is the health consequences of Covid-19 have demonstrated that it has unequal socioeconomic effects across population groups due to whatever reasons.

“And secondly, containment measures have not affected all groups in the same way as reported by the official regional office of Europe.

“So how do we measure equity? This is what we call the health equity impact plane. On the X-axis, we have equity impact; Y-axis, we have the net health benefit, of which cost-benefit has already been taken into consideration. So in this quadrant, we have a win-win situation. You have better equity, and then, you have improvement in health efficiency and health benefits.

“And here is a lose-lose situation. However, most of the time, societies or phenomena that we have observed fall into either this quadrant or this quadrant (win-lose quadrants). So with this quadrant, you have a loss in equity, but you have improved health benefit, and here you have an improvement in equity, but then you have a loss in health benefit,” Lee explained.

Lee said the value-based health care model is the way forward as achieving health equity alone will not be the answer to all the problems the Malaysian health care system faces, due to the current cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) being “grossly inadequate” due to the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) method of calculation.

The ICER method, according to Lee, provides the ratio of dollars per health benefit, and if equity is to be included in the policy factor, the Extended CEA (ECEA) ought to be used, as the ECEA includes non-health benefits, such as financial risk protection and distributional consequences such as equity, in the economic evaluation of health policies.

Alternatively, the distributional CEA (DCEA) can be employed as well. The DCEA provides distributional breakdowns of who gains most and who bears the largest burdens (opportunity costs) by equity-relevant social variables (for example, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, location) and disease categories (for example, severity of illness, rarity, disability).

When it comes to determining the cost effectiveness of health care strategies, individuals, businesses, and governments employ CEA to compare the expenditure and outcomes of two or more strategies for the performance of the same task.

The ICER measure or the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio is the ratio of the difference in costs between two strategies to the difference in effectiveness. This one-dimensional summary measure can be interpreted as the cost of obtaining an extra unit of effectiveness, and it quantifies the trade-offs between patient outcomes gained and resources spent.