KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 7 – The Malaysian health care system focuses on increasing longevity, but places little consideration on the quality of life, said University of Malaya consultant geriatrician Prof Dr Shahrul Bahyah Kamaruzzaman.

Dr Shahrul told the Health Policy Summit 2022 organised by the Ministry of Health (MOH) last month that in 2005, 60 per cent of the world’s ageing population lived in developing countries, and within a couple of decades, that number will increase to 80 per cent.

Older people will comprise one-fourth of the total urban population in less developed countries, with Dr Shahrul saying the demands of an ageing society must be met.

According to Dr Shahrul, in a panel discussion at the conference last August 15, this is part of a global phenomenon where “a lot of health care systems focus on longevity and not balancing the qualities of life that are needed”.

In Malaysia, the Department of Statistics stated in a 2022 report that the number of children aged below 14 years old decreased from 23.6 per cent in 2021 to 23.2 per cent in 2022, while the elderly, aged 65 and older, increased from 7.0 per cent to 7.3 per cent.

This makes Malaysia an ageing society, as per the United Nations definition, which categorises countries with 7 per cent of people aged 65 and older to be an ageing nation.

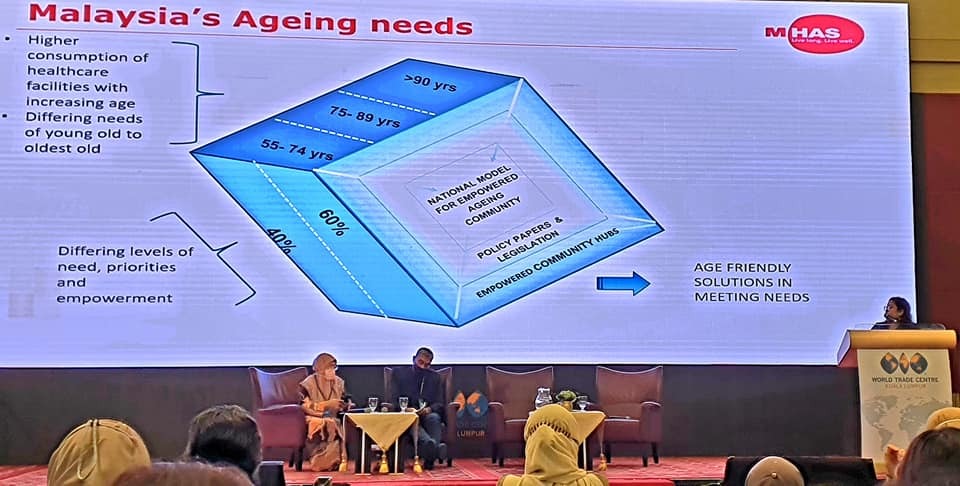

To tackle the ageing crisis, Dr Shahrul advocated for a SEE strategy that views the Social, Economic and Environmental determinants of health as stabilising factors and ensures that they are implemented through “education and awareness, health care, the technology to support it, the innovations, as well as the laws and policies which are regulated and implemented.”

When it comes to the implementation of such strategies, Dr Shahrul emphasised the need for proactive and cohesive measures, and not strategies that merely react to the changing needs of the older demographic.

As this older demographic is multidimensional, where “no one person is the same in their experiences of ageing,” strategies need to reflect this multidimensional demographic, said Dr Shahrul, who is also president of the Malaysian Healthy Ageing Society.

Rainbow Model Of Health

This multidimensional approach to policies and laws was also stressed by Prof David McCoy, lead researcher at the United Nations University-International Institute of Global Health (UNU-IIGH) and a speaker on the same panel.

He held that while health care is important when people are sick, health is determined by actions and the numerous governmental sectors promoting and protecting health.

He stated that the rainbow model of health, a systematic framework that illustrates the relationship between the approaches to health and total, whole-of-life development, is determined by societal factors. These in turn have an effect on the policies, laws, and regulations created.

“It is our policies, our laws, our regulations, our ideas, our beliefs that shape the way that this rainbow model is applied to populations and communities,” McCoy told the Health Policy Summit.

“So, when thinking about the social determinants of health, we are not just thinking about the social factors that impact our health, but also the way in which we produce our policies, laws, and regulations, the kinds of ideas and beliefs that we use when discussing and thinking about improving health.”

Though sharing the same views as McCoy on the importance of legislation and public policies, Dr Shahrul stressed more on the need for the empowerment of communities and the lack of reliance on political will.

She stated that the people have too long depended on political will, and they need to be more proactive by formulating community plans to ensure that reforms are carried out till the end.

“It is the community. The needs of the people, for the people, by the people…political will, it’s there but we cannot rely on it to get us to the next stage. We need to actually make plans for us within our communities to assure that this mandate is passed on from one to the next,” Dr Shahrul told the panel.

Dr Shahrul espoused the need for a health system that supports healthy ageing and a community-based societal solution that does not leave the old behind.

The consultant geriatrician held that the government needs to adopt a proactive approach and go down into the communities, study their needs, especially the needs of the old, and to remove the barriers to healthy and productive ageing “by improving our environment, making things a bit more socially accessible, and making it inclusive for all ages…bringing that health care support back into the community”.

“Right now, the right hand does not talk to the left hand, and there is miscommunication and standard of care depletes with every transfer of the patient from tertiary to primary, primary back to tertiary,” Dr Shahrul said.

Adolescents Treated Like Adults In Health Care System

At the Health Policy Summit, consultant paediatrician Dr Amar-Singh HSS stated that the Malaysian health system for adolescents, who make up 32 per cent of the total population, has not developed at the same rate as its system for adults.

Dr Amar, who is also an honorary senior fellow at the Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy, drew significant attention to the fact that the current health care system treats adolescents (12 to 17-year-olds) the same way it treats adults.

“Inpatient services for adolescents – they amount to about 15 per cent of the population, but currently, we treat them like adults. And we have a 12-year-old in a ward with a 70-year-old who is dying, which is totally inappropriate,” he said.

“Our policies must reflect that these adolescents are children, under 18, and we need appropriate services for inpatient…and appropriately trained staff.”

Currently, the MOH only recognises those under 12 as children. Adolescents are treated as adults and are made to share wards with adult patients.

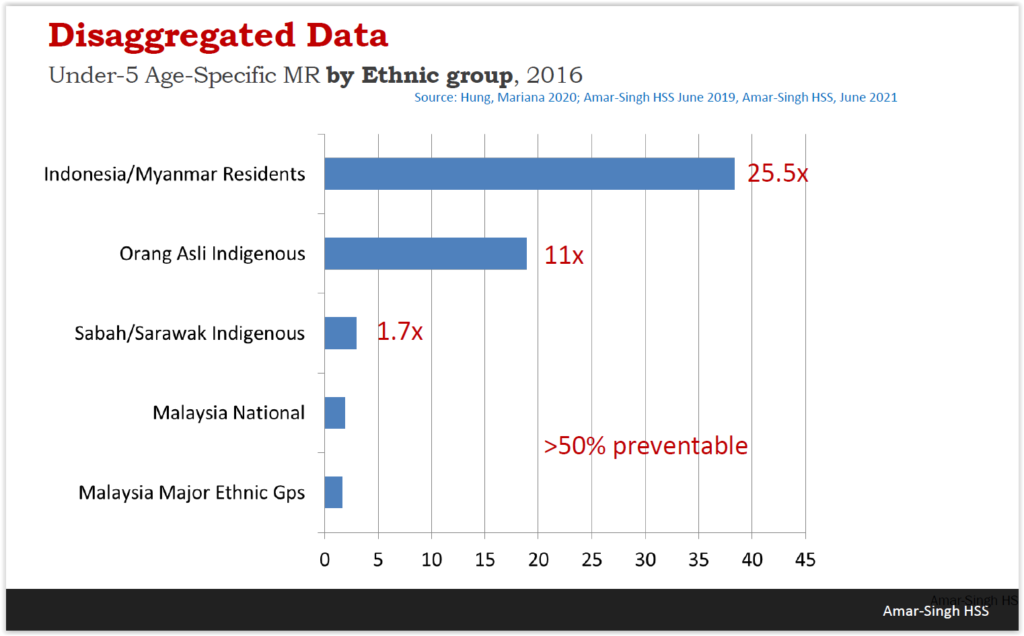

These failings, according to Dr Amar, are more grievous where the health of indigenous, Orang Asli, migrant, and stateless children are concerned.

He noted that the Orang Asli mortality rates for children aged under five are 11 times higher than major ethnic groups. Under-five indigenous children in Sabah and Sarawak have death rates that are almost double that of the general population.

On top of that, about 60 to 70 per cent of children from Orang Asli communities suffer from malnutrition by five to seven years of age.

During the question-and-answer session of the panel, Dr Amar said, “They are suffering from protein-energy malnutrition, so they die from simple things like diarrhoea, or simple pneumonia which would not threaten the average Malaysian.

“So, I don’t think their primary problem is prematurity or congenital abnormalities, their primary problem is a protein-energy malnutrition issue.”

Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) is a condition whereby people lack energy because there is a deficiency of macronutrients — carbohydrates, fat and protein. Commonly found in patients with chronic liver disease, this condition is also a problem for children in developing countries who are not provided with enough calories and proteins.

The lack of macronutrients for Orang Asli children stems from a loss of forests and the fact that 80 per cent of them are living in abject poverty, Dr Amar said.

Traversing the realm of infrastructure, Dr Amar informed the Health Policy Summit that the issue of poverty is one that affects an estimated three to four million children nationwide, with greater impacts being felt by migrant, refugee, and stateless children.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which Malaysia is a part of, has not been upheld in Malaysia, leaving many migrant, refugee and stateless children without basic health care, said the consultant paediatrician.

The majority of these children, according to Dr Amar, do not receive their routine primary immunisation or regular growth and developmental monitoring. They are also not privy to health advice and education.

Besides shedding light on the violation of rights, Dr Amar emphasised the need for Malaysia to invest more in preventing deaths unrelated to illnesses.

About 60 per cent of children aged one to 18 either die on the road or drown, and to put things into perspective, for every child that dies from dengue, about 30 will have died on the road and 10 will have drowned.

In addition to these numbers, about 1,500 children die annually from injuries.

Disaggregate Data, Map Out Communities, Decentralise Services

“If you want to address child health, you need to have an evidenced and data-based approach and areas with large health burdens must not be neglected,” Dr Amar said.

He also called for public dissemination of disaggregated data, mapping of communities, compulsory death registration and mandated medical certification of deaths by law, and a decentralisation of services — which means spreading out health care expertise throughout communities.

“We need to reverse the inverse care law. The inverse care law is one where those who need health care the most are the ones least likely to get it. We need to reverse this and target marginalised communities specifically. And for this disaggregated data is critical,” stated Dr Amar.

This view of an evidenced-based mapping approach was a view shared by both his co-panellists and other panellists throughout the Health Policy Summit.

McCoy stated that for such systems to be truly effective, there needs to be a good organisational infrastructure at all levels and different frameworks for each level of the structure.

“A lot of that has been built around district-level management. Districts which have a very clear population that people have been responsible for. Not too big, not too small, just the right size to enable effective coordination and cooperation in terms of the implementation of the multisectoral organisation,” McCoy said.

“And to ensure that there is community empowerment, community involvement, ensure the right mix of bottom-up development and top-down direction.”

Community care hubs, a model of care that Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin seeks to introduce in the Health White Paper, was visualised as community empowerment by Dr Amar.

“I like the word that Shahrul used about community care hubs, but I would call it community empowerment hubs. They are not ‘care’ per se, but it’s a place where we empower the community to look after their own health.”