Sarawak (124,450km2) is 95.3 per cent the size of Peninsular Malaysia (130,590km2). Kapit division (38,934km2 or 31.3 per cent the size of Sarawak) is the largest of its twelve divisions.

The divisions in Sarawak mark the new areas ceded by the Brunei Sultanate to the White Rajahs since 1841. By 1912, Sarawak had five divisions, corresponding to territorial boundaries of the areas acquired by the Brookes, hence their unequal sizes.

In 1973, the sixth and seventh divisions were carved from the third division.

Compared to the 2021 Malaysian population density of 99 people/km2, Sarawak has the lowest population density with 23/km2, followed by Pahang at 47km2 and Sabah at 52km2. Kuala Lumpur has the highest population density with 7,188/km2, followed by Putrajaya at 2,354km2 and Penang at 1,691km2.

46 per cent of East Malaysians live in widely scattered villages in the rural areas compared to 20 per cent in Peninsular Malaysia and the national average of 29 per cent.

The Flying Doctor Service (FDS) was introduced as a pilot project in Sarawak in September 1973 to strengthen health care service delivery to these difficult-to-reach communities.

The first phase covered an estimated population of 85,000 in 40 locations, which were visited once a month, using helicopters from the Malaysian Air Force for the southern region, and Southeast Asia (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd for the northern region.

It is interesting to note that one of the FDS’s objectives was “to make the objectives of the government felt in these remote locations which otherwise could easily fall prey to the influence of insurgents” (communists).

The FDS became a permanent service in May 1975 with the acquisition of two Bell helicopters, increasing to three in 1977, covering 227 locations. The seventh division had 52 FDS locations in 1977. (Heritage in Health: The Story of Medical and Health Care Services in Sarawak, pages 295-300).

It is interesting to note that the Sabah State Health Department started its own FDS in 1978, gradually taking over the service initiated by the Sabah Foundation.

As the capacity of the Bell helicopter is limited to four passengers, a standard FDS team will consist of a doctor, a medical assistant, and two midwives or community nurses.

The doctor could be the Divisional Medical Officer (DMO) or from the local hospital. Sometimes, the state maternal child health, tuberculosis or malaria officer may take this opportunity to make a supervisory visit to the clinics via the FDS. He would take the place of the doctor and handle the FDS clinics.

Likewise, a senior medical assistant or health sister may substitute for the same category of staff to carry out supervision.

The other staff were permanent members of the FDS team from the DMO’s office. This ensured continuity and enabled the FDS staff to get to know the locations, local issues, headmen, and volunteers (village health promoters).

Their duties included collecting follow-up medications for chronic mental, TB, leprosy, or cancer patients from the hospital pharmacy and sending to them in the FDS locations, thus ensuring better compliance. Often, we also carry letters for other agencies, for example, the school used as the FDS clinic that day.

When it comes to disaster relief, the FDS staff were always recruited to help pilots not familiar with the division to locate nomadic Penan settlements, as these were not well-marked on the usual maps and tended to move about.

Of all the government departments, the DMO was the one most familiar with the aerial view and their latest locations.

in 1982, the Upper Rejang and Kapit town was flooded up to 18 feet in places. It was so deep that I had to take a longboat to get to the DMO office from the hospital quarters!

I was asked to join the relief team on the Malaysian Airforce Nuri Helicopter to help drop off food items to the flooded Penan settlements.

The pilot was unfamiliar with the area, so I was called to the open door of the Nuri to see if I recognised the village below. It was scary indeed.

First of all, I do not like heights. Unlike the navigator who was nicely secured and strapped to the helicopter, I was loosely attached with my hands to the wall of the shaking craft and was trying to avoid being blown out of the open door.

Under the circumstances, I must admit, giving the pilot the most accurate location was the last thing on my mind. I just wanted to get back to my seat belt as soon as possible.

As the DMO, I had to fly on 10 of the 12 flying days. There were only two medical officers in Kapit Hospital then, so they took turns on the other two days.

The helicopter would come in early in the morning from Kuching or Sibu on the first day of the week, and land on the hospital’s basketball court. We would load up and take off early because we needed to be back in Kapit before sunset.

It was really very beautiful, flying off into the early morning mist and low clouds, over the Rejang. On some days, we would see hornbills below us flying above the tree canopy.

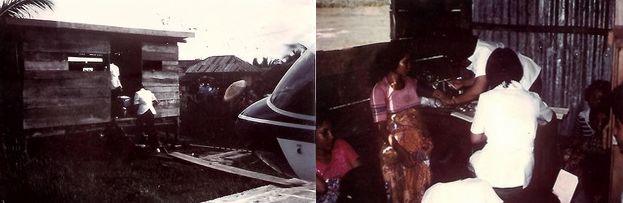

The FDS clinics were usually set up in school classrooms, simple sheds, or the longhouse. In some Penan settlements, we would review patients within the limited shadow of the helicopter.

When we land at the village, usually a school field or clearing, marked with a very large white cross, the villagers would be waiting to help bring the boxes of medicines.

The villagers would have been informed of the schedule several months prior and confirmed by repeated dialect announcements over Radio Malaysia Sarawak and local newspapers.

The two nurses would see the pregnant mothers and children for growth measurements and vaccination, while the medical assistant would screen the adults.

More difficult cases, including from the nurses, would be referred to the doctor. Most of the patients were those who are not that ill but trying to get some free medications. This is quite understandable, since the nearest clinic is far away and costly in money, time, and effort to get to.

Depending on the distance from Kapit and the size of the village, we would cover two to four locations per day. We brought our own packed lunches and drinks.

There was one village where there were so many flies that the pilot said: “When you kill one fly, one thousand comes for the funeral”. We avoided eating there and would finish work and take off to eat elsewhere or on board.

We had great pilots, the regular ones who got to know the division well. They always reassure the newbies that helicopters are a lot safer than planes.

One Vietnam War veteran would demonstrate this by cutting off the engine while it was quite high up and showing how he could manoeuvre and land it without any power. We only needed a clearing the size of a badminton court for safe landing.

He was extremely experienced from his service during the war. Unfortunately, on his way out to the Baram to answer a medevac call one stormy evening, he crashed in the thick jungle. It was a horrible loss for all of us, when search and rescue found the debris.

One time, when the FDS team had not returned to Kapit by 5.00pm, I became worried. I called air control in Kuching, which was supposed to keep track of the helicopters, as Kapit airport lacked the facilities to do so.

The air control officer then very coolly said: “Oh, we have not heard from the pilot since 2.30pm”.

I panicked and asked him why he had not alerted us at the DMO office. He said: “Maybe they just stopped somewhere for makan?”

When the control tower failed to contact the pilot by nightfall, a deep gloom fell over the medical community. We had to prepare for the worst. The search and rescue helicopter could only fly in the next morning.

We called up blood donors. It was a terrible night for all. As we were expecting multiple casualties, I was the only one who could accompany the pilot. There were a lot of tears among the medical staff as we loaded the stretcher, blood packs, and splints.

Thankfully, the search and rescue pilot knew the area well. We were so relieved when we saw the intact FDS helicopter in Punan settlement, where the last FDS location was. Something had happened to the engine and the aircraft was unable to lift off, so the pilot was unable to call for help.

The doctor, medical assistant, and two midwives were so relieved to see us. They had stayed the night in the settlement in the clothes they wore. They ate the meagre lunch they brought.

The villagers were kind enough to prepare breakfast, which was some sort of snake soup with tapioca. It was very basic, as these are nomads who do not do any sort of cultivation. Some do not eat even fish, which the river had an abundance of.

We had a great celebration when both helicopters managed to return to Kapit. In those days, the travelling staff, especially the FDS team, were not covered by special insurance, despite the very real risks.

Once I flew with a new pilot. The morning clouds were exceptionally thick, so he decided to fly along the river below the clouds. Unfortunately, as the river got narrower, and the overhanging tree branches got menacingly close to the helicopter propellers.

He turned and asked me nervously: “Doc, do you think the top of the hill is over there?”, pointing to thick clouds which had enveloped the treetops. O.M.G.

Dr Tan Poh Tin, proudly Sarawakian, is a paediatrician and public health specialist. She says: “Sarawak – to know you is to love you.”

- This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of CodeBlue.