MONTREAL, Sept 14 – People who inject drugs (PWID) in Malaysia reported frequent physical police violence and arrests, increasing the likelihood of needle sharing, a major risk factor for HIV and Hepatitis C infection.

These experiences may also impede PWID from accessing HIV and hepatitis testing and life-saving treatment services.

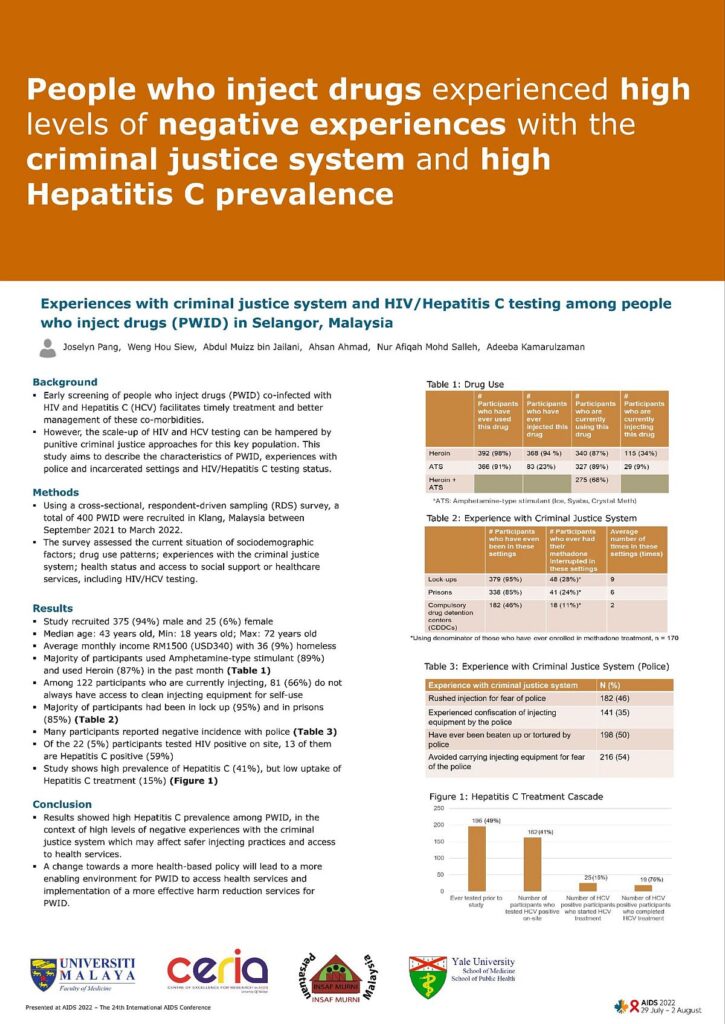

A study on injecting drug users’ experience with the criminal justice system conducted by University of Malaya (UM) found that the overwhelming majority (95 per cent) of 400 drug users surveyed in Klang, Selangor, had previously been detained in lock-up, while 85 per cent have been in prison.

Half of the participants claimed they had been beaten up or tortured by the police, while 35 per cent said they had experienced confiscation of injecting equipment by the police.

Nearly all (98 per cent) have used heroin, although current use of heroin is 87 per cent amongst respondents. About 91 per cent of respondents said they used amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS), such as ice, syabu, and crystal meth, with 89 per cent saying they currently use ATS.

The majority (94 per cent) of those who participated in the study from September 2021 to March 2022 were male, aged 18 to 72. Nine per cent identified themselves as homeless; the average monthly income among all respondents was RM1,500.

The findings, which were presented at the 24th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2022) in Montreal, Canada, on July 31, raise fresh concerns that police aggression and arrests of people who use drugs may affect safer injection practices and access to health services.

Needle and syringe exchange programmes, primarily involving the provision of clean needles and syringes to people who inject drugs and collecting old, used needles and syringes, remain one of the main harm reduction approaches in Malaysia to reduce HIV vulnerability among PWIDs.

“That’s the irony of it, right,” said UM PhD candidate Joselyn Pang, referring to police confiscation of injecting equipment. Pang presented the study in Montreal.

“When we developed a guideline with the police, we made it clear what the package of harm reduction was. In fact, they were supposed to know that this (needle and syringe exchange) is part of the harm reduction programme that is related to health.

“But I think over the years, people have kind of forgotten about it. They are not sensitised at the ground level, so, a lot of them (the police) may not understand what harm reduction is,” Pang told CodeBlue in an interview at AIDS 2022.

“You still see that they confiscate needles, which is not right, and that is a huge challenge. There needs to be better coordination and dialogues among agencies such as health, enforcement, and civil societies, to ensure well implemented harm reduction and treatment programmes.”

The study also showed that 46 per cent of respondents said they would rush injection for fear of police, while 54 per cent said they would avoid carrying injecting equipment due to their negative experience with the criminal justice system.

In Malaysia, the needle and syringe exchange programme (NSEP), first introduced in 2006 by the Ministry of Health (MOH) in partnership with the Malaysian AIDS Council, is a central component of the government’s harm reduction strategy, as outlined in the National Strategic Plan for Ending AIDS 2016-2030 (NSPEA).

Harm reduction refers to policies or programmes that aim to minimise the health and social harms associated with addiction and substance use, without necessarily requiring people who use substances from abstaining or stopping.

While new HIV cases and the proportion contributed by PWIDs have seen declines over the past two decades, access to treatment continues to be limited.

In 2020, the quantity of needles and syringes distributed per PWID in Malaysia in 2020 decreased by more than 50 per cent compared to 2016, according to the MOH’s Global AIDS Monitoring 2021 Progress Report. From 2019 to 2020, the decline was 15 per cent.

The federal report attributed the reduction in needle-syringe distribution that year to Covid-related movement restrictions and increased uptake in opioid substitution therapy. Despite efforts to make NSEP points available at government health clinics during lockdowns, it was noted that PWIDs’ access to health clinics were restricted, leading to fewer needles distributed.

Apart from HIV, the UM study also found a high prevalence of Hepatitis C among injecting drug users at 41 per cent, although uptake of Hepatitis C treatment is low at 15 per cent.

“Many of them (injecting drug users) have not even thought about Hepatitis C. Only half of the study’s participants or PWIDs have done a Hepatitis C test before. So because the knowledge of Hepatitis C is low, the result is they are not getting treatment because they don’t even know their status,” Pang said.

In Malaysia, prisoners and detainees in jail or compulsory drug detention centres are subjected to mandatory HIV testing, but not Hepatitis C testing.

“I think we need to review the legal environment because that is the biggest issue for PWID, accessing care, in my opinion,” Pang said.

“Of course, there needs to be further studies on this but clearly both data are showing that when you have a legal environment that is punitive, it’s going to increase the risk for getting blood borne viruses and stop people from coming forward for treatment or interrupt people from coming for treatment.

“If I’m on methadone and I’m arrested the next day and I have no access to my treatment, when I’m out of this lock-up, for example, I have missed 14 days of my methadone treatment and I will have to restart everything again. Just talking about it is sad and exhausting,” Pang said.