KUALA LUMPUR, March 7 – Children under the age of 18 who are suspected of having suffered physical, emotional, and sexual abuse in Malaysia must be examined by paediatricians trained in child abuse, a paediatrician said.

Senior consultant paediatrician and researcher Dr Amar-Singh HSS said he has increasingly noticed in recent years that some children reported as possible abuse victims to the Welfare Department are not brought to paediatricians for examination.

In these circumstances, Dr Amar said the Welfare Department appears to determine there is no abuse on its own accord, denying children appropriate access to health services.

“Note that approximately 30 to 40 per cent of all children under 18 years who are identified as sexually abused are often classified as ‘rape’ and may not be referred to the Welfare Department or paediatricians and only reported to the police,” Dr Amar told the Medico-Legal Society of Malaysia’s (MLSM) “Speaking for the Unspoken – Children of a Lesser God” webinar on February 12.

Hospital Tunku Azizah consultant paediatrician Dr Yap Hsiao Ling said doctors are duty bound by the Child Act 2001 to report incidents of child abuse or neglect to a protector, referring to an officer at the Social Welfare Department (JKM).

Under Section 27(2) of the Act, a medical officer or registered medical practitioner would have been deemed to have committed an offence and can be fined up to RM5,000 or imprisonment not exceeding two years on conviction.

“I wish that when I was a very young junior medical officer that I would have had formal training in identifying, reporting, and managing child abuse cases. This is the part that is actually lacking in Malaysia, and I still feel that it still is, although there’s some improvement right now, but it’s still lacking at most training centres,” Dr Yap said.

She said a lot of child abuse cases in Malaysia go unreported by medical workers due to the general lack of awareness on their role to report abuse, their lack of knowledge on the reporting procedure, as well as fears of getting involved in the case and possible litigation.

Dr Yap said lack of awareness on reporting child abuse cases meant that many doctors may not know the procedures involved to report or would prefer to not get involved in.

“Many do not want to have the hassle of going through the process once you’ve reported it.

“Once you’ve made a police report, the police will come to find you for investigation purposes. JKM will need you to give a report about your documented findings. And if the case ends up in court, you will have to be an expert witness,” Dr Yap said.

However, Dr Yap stressed that failure to report a suspected child abuse case not only goes against the law, but may ultimately lead to adverse outcomes that put the child’s life at risk.

On being sued, Dr Yap pointed out that Clause 123 of the Child Act 2001 states that legal action shall not be brought against doctors who made the report in good faith, in the reasonable belief that the child was abused.

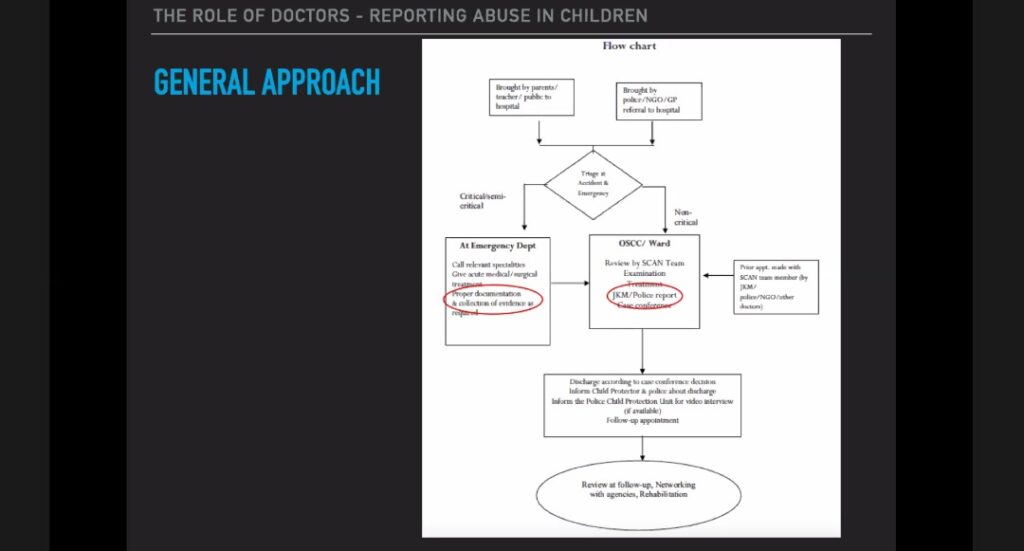

While citing a Ministry of Health (MOH) flowchart on how to report a child abuse case, Dr Yap noted that once the chain of reporting has started, documentations are critical.

“Make sure everything is done properly – the documentations, the collecting of evidence – everything is included in assisting the police for investigations.

“If you don’t do that, what happens is many of the reported cases do not actually even reach the courts,” Dr Yap said.

About 6,000 to 7,000 children are reported as abused yearly, though Dr Amar said this is gross underreporting as three local community prevalence studies on child sexual abuse showed rates of between 8 and 26 per cent of all children.

Data from community studies on maltreatment of 15- to 17-year-olds in 2006 and 10- to 12- year-olds in 2011 showed at least half have some form of physical or emotional abuse and live in uncertain home environments.

The Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) also reported incidents of abuse in child care centres and education institutions, including tahfiz schools.

“There is no clear idea on the number of unregistered tahfiz schools but media reports suggest hundreds just in the Klang Valley alone; often abuse is covered up in religious centres.

“In addition, the vast majority of childcare centres or nurseries operating are unregistered, which is estimated to be in excess of 50,000,” Dr Amar said.

In 2016, the Women, Family and Community Development Ministry stated that only 4,240 nurseries and 1,650 child care centres were registered with the Welfare Department.

“Unregistered child care centres or nurseries are of concern as to the potential for poorer children care and lack of supervision,” Dr Amar said.

Schools are also not uncommon locations for abuse to occur, but often, the investigation is internal and no report is made to the relevant authorities.

“Over the years, as a paediatrician, I have experienced a number of occasions where teachers have abused children; physically, sexually and emotionally. The classical response is to transfer teachers to another school.

“This denies the reality that these teachers may continue to abuse children in the new school and, in addition, the child does not receive appropriate support and care.

“Despite the mandatory nature of the Child Act 2001, the empowerment of Social Welfare Officers as ‘child protectors’ and the vast and comprehensive powers conferred on them, the Welfare Department often appears to be powerless,” Dr Amar said.